The Frappuccino Funk: What’s Ailing Starbucks?

When a ubiquitous popular brand loses its way, the reasons can be complicated, and the fixes formidable.

In the case of Starbucks, which has been plagued by bad news lately as its sales have dipped four quarters in a row, the fixes may not be so complex. In fact, one may be tempted to say they amount to comfortable couches, Sharpie markers, and a condiment bar.

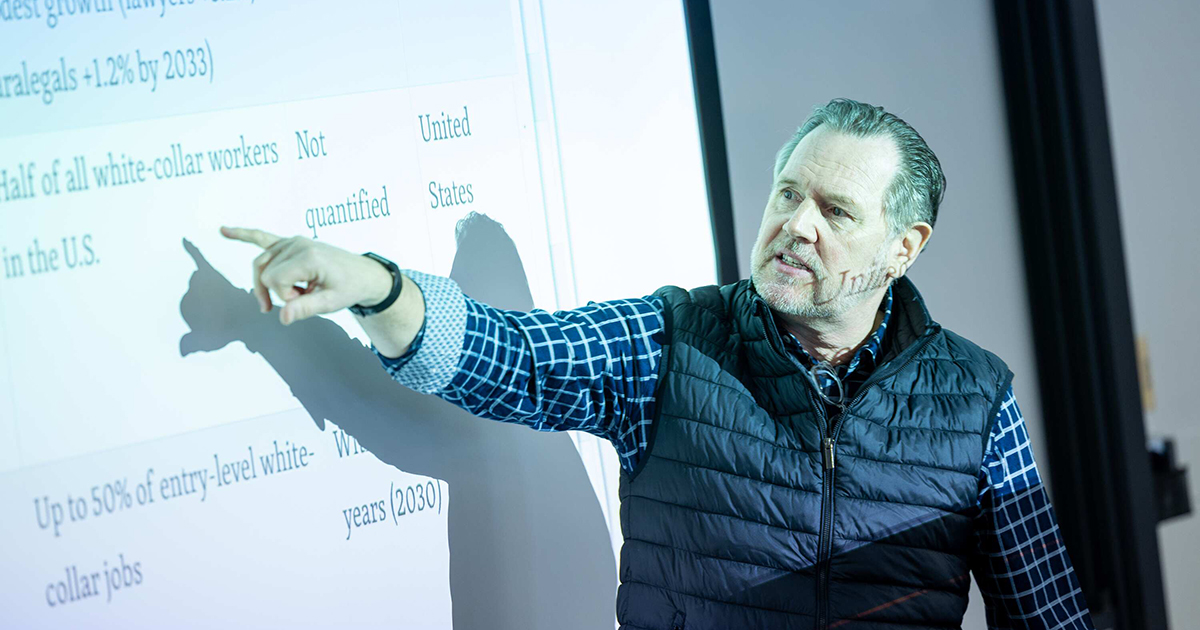

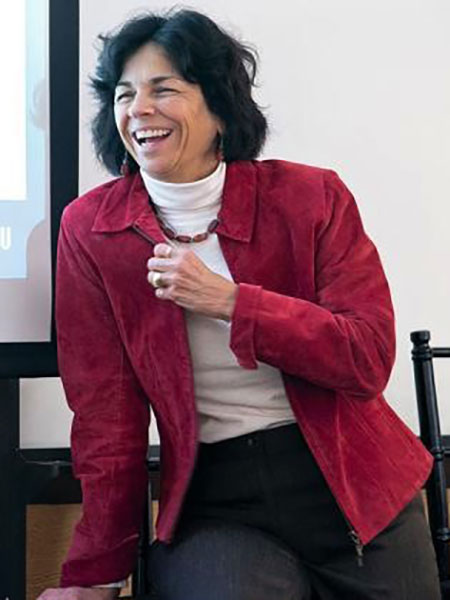

“The primary problem I see is their operations have gotten far removed from their original value proposition,” says Gina O’Connor, professor of entrepreneurship at Babson and the Fischer Family Term Chair in Healthcare Management.

That original value proposition was based less on coffee and more on the cozy, welcoming vibe in the café. “It was a place to commune,” O’Connor says. “In the beginning, many people didn’t love the taste of the coffee but really appreciated the atmosphere.”

Faced with changing leadership and an inability to readjust after the calamity of the pandemic, Starbucks seemingly has lost touch with the core of its identity. Its cafés have become, not so much homey places to hang out, but nondescript spaces with reduced seating where people wait in long lines to pick up orders from stressed-out baristas. “You order online and leave,” O’Connor says.

O’Connor is an expert on innovation, particularly breakthrough innovation that can change the dynamics of a market. While O’Connor believes that Starbucks could experiment with innovation in its cafés, say by trying out new efficient ordering systems, its issues feel much more basic. “They have less to do with innovation and more to do with execution and forgetting why customers were so happy with them,” she said.

Last year, Starbucks hired Brian Niccol, formerly of Chipotle, as CEO to right its caffeinated ship. He has implemented a plan he calls “Back to Starbucks,” and the company’s recent Super Bowl ad, titled “Hello Again,” promises that “the Starbucks you love is ready.” O’Connor reflects on these efforts and offers her thoughts on how the coffee giant lost its way and how it can find its way back.

What Went Astray

Perhaps saying that Starbucks can solve its problems simply by adding some cozy couches is a bit simplistic. Then again, its issues probably feel obvious if one has spent time in its cafés.

Take the detailed, time-consuming customizations that customers often ask for with their orders. Three pumps of that flavor and a pump of that one, they may say, with a shot of espresso and whipped cream. “Whatever you want, you get it, but it takes a long time,” O’Connor says. “It turned into all these long lines of people waiting and the rest of us who aren’t willing to wait anymore.”

Adding to the problem was the fact that, during the pandemic, Starbucks took away its condiment bar, which meant that baristas had to add milk and sugar, things the customer could do themselves. “You have to ask for it, and that holds up the line more,” O’Connor says.

Because the baristas are so pressed to fill complicated orders, they have less time to interact with customers, to make small talk or write a greeting on a coffee cup with a Sharpie marker. Those simple gestures were one of the crucial things that gave Starbucks its homey atmosphere.

Without that warm ambiance, Starbucks loses a key differentiator as its prices have gone up and as it faces an increasingly competitive coffee marketplace. “The high prices may not have been a problem if they kept the communal part there,” O’Connor says. “You pay double what you would for a cup of coffee. You can just go to McDonald’s and get Newman’s Own coffee.”

Staging a Turnaround

As the years have passed, Starbucks feels further removed from Howard Schultz’s vision for the company as a “third place” between work and home. While not the founder of Starbucks, Schultz was a consequential entrepreneurial leader who built the company into the coffee behemoth it has become.

“As you change from the founder to the second and third generational leaders, you lose the sense of the entrepreneurial vision,” O’Connor says.

Realizing that the vision has been lost can take time. When a company experiences a bumpy patch, its leaders may be slow to realize the root causes. “It can take a while,” O’Connor says. “People think it’s the economy. It’s inflation. It’s this. It’s that.”

“The primary problem I see is their operations have gotten far removed from their original value proposition.”

Gina O’Connor, professor of entrepreneurship and the Fischer Family Term Chair in Healthcare Management

If she were running Starbucks, O’Connor says, she would conduct market research to understand just how important a comfortable atmosphere is to customers. She also would look hard at the operations of cafés and the relationship between baristas and customers. Starbucks was once known as a company that empowered employees and gave them strong benefits, a commitment that seems to have faded. O’Connor would want to fix that. “It can still be a culture where you feel valued and feel cared for,” she says.

For its part, Starbucks is taking measures to address its problems. The company recently brought back the condiment bar, for instance, and began offering free refills to customers who stay at the café to drink their order. O’Connor says the company is well-positioned to stage a turnaround. “They are not at an alarmist level,” she says. “They have time. They have a great brand. They have great locations.”

Posted in Insights