Exploring an Integrated, Systems Mindset

You first see giant egg structures when you drive onto Deer Island. They look like alien pods, greeting flights as they take off and land at nearby Logan International Airport. To get to the top of them, you take a giant elevator reminiscent of the one Charlie rides to get into Willy Wonka’s factory.

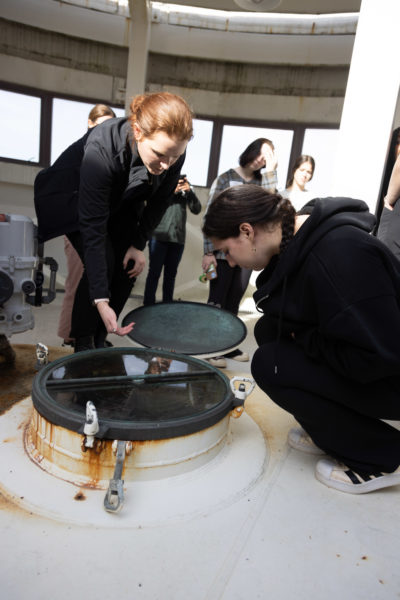

On a sunny, warm November Friday afternoon, a group of Babson students steps into this elevator as part of a Socio-Ecological Systems (SES) class field trip. Instead of a candy factory, they are exploring a feat of engineering and politics, and the egg-shaped anaerobic digesters are just one part of a complex water system that keeps Boston Harbor clean after decades of debate, money spent, and federal lawsuits.

“Once we got here, I had an urgency to know this stuff,” Charlie Wang ’25 said. “It blew my mind to see how this big of an operation works.”

Small Steps to Big Impact

SES is a cornerstone of the Babson curriculum—and this trip to Deer Island Wastewater Treatment Plant, in Winthrop, Massachusetts, is a new cornerstone of the SES Water Systems course. Led by Visiting Assistant Professor of History & Society V. Miranda Chase and Assistant Professor of Environmental Science Sarah Foster, it is an experiential opportunity in a class designed to teach students to think beyond one aspect of a project. And, to learn literally what happens after you flush.

SES provides hands-on learning opportunities for students to explore sustainability.

“It’s not a science class with social aspects. We think of it as a systems course. It’s not just the entrepreneurial mindset. It’s not just the scientific mindset. It’s not just the social, advocate mindset,” Chase said. “We want them to have an appreciation and understanding for any situation as a system and what are the multiple ways you can look at something and create partnerships and collaborations in your future ventures. We want to get them to think in this system’s mindset.”

SES is one of three foundational courses Babson undergraduate students take as part of the College’s new curriculum, introduced in 2021. It’s a liberal arts and sciences course co-taught by two faculty members—one trained in science, another in the humanities or social sciences—that is designed to demonstrate the role humans play in damaging and protecting nature and how tomorrow’s environment is affected by what humans have done and will do across their personal and professional lives.

Students are required to take one of six topics on integrated sustainability (Water Systems, Climate and Economic Systems, Food Systems: Feeding the Modern United States, Urban Systems, Prairie Systems, and Systems & Disaster Resilience) in their second or third year, which can later be expanded on through other science, social science, and humanities courses.

“When I first signed up for it, I didn’t know what a class about water was about,” Sebastian Salazar ’25 said. “Now, halfway through, I know there are multiple components to how we treat water and how us humans have treated it really badly.”

The egg-shaped anaerobic digesters are the most prominent part of the Deer Island plant.

These aren’t topics you expect to explore at a business school, and that’s the point. As the idea of social impact and corporate social responsibility grows, it has become more imperative that future entrepreneurial leaders use systems thinking to address operations holistically, from the personnel needed to run them to a company’s environmental impact.

Why Systems Thinking Matters to Business

The Deer Island Treatment Plant, operated by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, is the second largest of its kind in the country and is why dirty water is now mostly known for Fenway Park sing-a-longs instead of as a reality for Massachusetts residents. It came about because of a federal court ruling in the 1980s, as part of the Clean Water Act, mandating the state clean up the pollution in Boston Harbor. It treats wastewater from 43 greater Boston communities, some all the way from Framingham, with a daily amount equaling roughly the volume of the Charles River.

“I hope they do learn things about water and the importance of water and how it’s integrated into everything in our lives, but I also think fundamentally it’s about teaching them the ways we can try to make changes and to foster more sustainable systems. These are tools that apply to whatever they want to do.”

Sarah Foster, Assistant Professor of Environmental Science

The cleanup is one of five case studies the class works on throughout the semester. They cover each from three modules: the stocks and flow of materials in the system; how the systems can be more sustainable; and finally what can communities, humans individually, businesses, and governments do to make them more efficient and sustainable.

“At a business school, you may get bothered by a science class. But (Chase and Foster) don’t just say, ‘This is important because.’ At the end of every class, they relate it back to entrepreneurship, the economy, innovation, social impact—it’s all connected,” Lindsay Gaziano ’23 said. When things are thought of systematically, you can find avenues to address all aspects of them.

More Than Just a Pollution Problem

Chase and Foster cite the plant as an example of how thinking in systems—and finding ways to close loops within those systems—can lead to positive results. The engineering upgrades to the Deer Island Treatment Plant are successful in addressing water pollution in Boston Harbor, and also successful in self-generating a large portion of the plant’s electricity needs while minimizing atmospheric pollution. Instead of being dispersed into the atmosphere, the methane gas collected in the egg-shaped anaerobic digesters is then used to power the plant, closing an energy loop within the system.

SES teaches students the collaboration skills they will need to successfully address challenges in their professional pursuits.

As with all real-world, large-scale projects, there are unintended consequences the plant and its stakeholders can continue to address, demonstrating the need for iteration and integrated thinking for projects like this. The improved water quality in Boston Harbor has led to gentrification and rising house prices for once-affordable areas by the water. Additionally, the harbor still receives raw, untreated sewage from combined sewer overflows when there is heavy rain, and the treated wastewater the plant creates is discharged 9 miles out into the ocean instead of used for agriculture and human use.

For Chase and Foster, the field trip is a chance for exploring a sewage plant in the fresh air, community engagement, and a hands-on look at a real water system. The entire course, though, is about arming students with the systems-thinking and collaboration skills they will need in the future to successfully address challenges and close loops in their own ventures.

“The principles of systems thinking are important to us. We are hoping they realize how things are interconnected,” Foster said. “I hope they do learn things about water and the importance of water and how it’s integrated into everything in our lives, but I also think fundamentally it’s about teaching them the ways we can try to make changes and to foster more sustainable systems. These are tools that apply to whatever they want to do.”

(Photos: Mark Manne)

Posted in Community, Entrepreneurial Leadership