She Empowers Women Artists in India

Artists may know how to make art, but they don’t always know how to make money.

This is something that Sonal Dalvi MBA’23 has witnessed firsthand. She grew up in Mumbai, watching her mother struggle to create art that others might buy. “Artists have a different mind,” she says. “They follow their heart.”

Following one’s heart can make for a tough career, particularly if artists are unwilling to cater to the marketplace or pursue work that feels too commercial. “Commercial is a word that is taken negatively,” Dalvi says. “They don’t understand the market, and the market doesn’t value them.”

Dalvi has worked for a long time to change that. In 2009, during her last year in college, she sought to assist her mother to sell her art. Dalvi thought she would help her for a couple of years before moving on to other pursuits.

Instead, 14 years later, Dalvi’s work with artists has greatly expanded. With her social venture World Village Bazaar, she now seeks to help women artists in India whose traditional forms of artwork are in danger of disappearing. Her efforts have caught the attention of the Clinton Global Initiative. “We are losing all these art forms,” she says. “I thought that, instead of just helping my mother, I should help other artists as well.”

Dalvi wants artists to have careers that are rewarding, profitable, and empowering. “How do you get a sustainable income? How do you feed your family or yourself?” she says. “It’s important to find ways to have an income out of it.”

Helping Her Mother

Dalvi grew up with her two sisters in a small house, and they watched their mother as she worked in her workshop. Their mom, Poonam Padukone, liked to create murals made out of wood, and they saw how she longed to have her work be more appreciated. It was the household’s primary source of income.

Sonal Dalvi MBA’23 (right) discusses her World Village Bazaar social venture with Chelsea Clinton (left). This year, Dalvis is attending Clinton Global Initiative University, a program for those dedicated to finding solutions to the world’s challenges.

“We struggled with money. Those were difficult times,” Dalvi says. “We would always think, ‘Why won’t she get a job with a salary?’ ”

Dalvi’s mom encouraged her to be an artist as well. Dalvi resisted. “I saw her struggle. I didn’t want to be a part of it,” she says. “I wanted a normal job.”

Dalvi studied accounting in college, and with the skills she learned, she decided to help her mother, though finding the right approach to sell her art took time. At first, Padukone pivoted to make name boards, a common household item in India that hangs on the wall and lists a family’s surname, and they proved popular.

They were so popular, in fact, that Dalvi opened four kiosks in Mumbai malls to sell them. But then competitors popped up, competitors who could mass produce the name plates and sell them cheaper. “I couldn’t keep up with that,” Dalvi says. The kiosks were closed, and another pivot was needed.

This time, Padukone began making murals for hospitals and other public institutions, and this proved to be a winning idea, especially considering those murals are typically paid for by corporations seeking to give back to their communities. “It’s going well,” says Dalvi of Applik Exotica, the venture that sells her mother’s work. “So far, so good.”

Preserving Tribal Art

More expansive artistic efforts have followed. As Dalvi began to work with other artists besides her mother, she founded Glasika Craft, which sells painted glassware such as oil lamps. To paint the glassware, Glasika partners with a local NGO that works with women artists from the Warli indigenous tribe of western India.

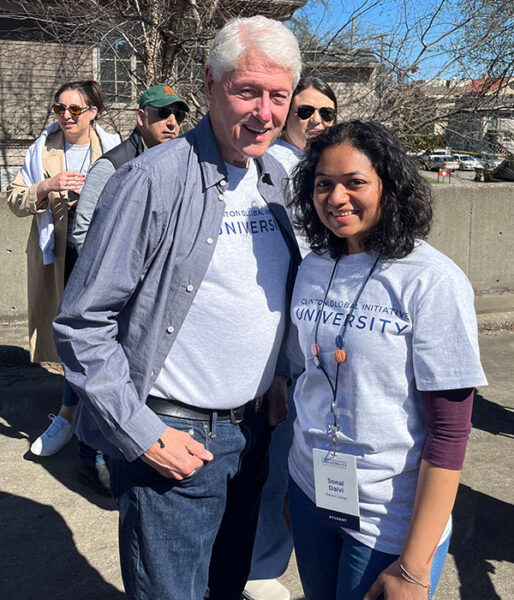

Sonal Dalvi MBA’23 (right) stands with former President Bill Clinton (left). Clinton Global Initiative University is mentoring Dalvi on how to implement World Village Bazaar on a larger scale.

In all, 10 women artists paint for Glasika. This work enables them to not only earn an income, but it also allows them to practice and preserve their art. It’s an effective model, and with other tribal art forms in India at risk of fading away, as people from rural areas move to cities, Dalvi wondered what more she could do. “If we are able to preserve this art form,” she says, “can this be replicated in other areas?”

That’s what led her to found World Village Bazaar. Building upon her accomplishments with Glasika Craft, she now hopes to connect with other traditional artists in India and the NGOs who work with them. The goal is to find retail companies interested in selling their art around the world. “It has to be a sustainable model,” she says. “I don’t believe in fundraising or having donations for them. These art forms do not need sympathy.”

For her work with World Village Bazaar, Dalvi was accepted into the Clinton Global Initiative University, a program for those dedicated to finding solutions to the world’s challenges. The program, which runs through October, is mentoring Dalvi on how to implement World Village Bazaar on a larger scale.

Dalvi works on World Village Bazaar while holding down a full-time job in the finance department of the Boston Public Health Commission. That makes for a busy life, but she admires artists and the beauty they create. “I can relate well with them,” she says. “I love the fact that they are so talented.”