In the Classroom, Students Design for Sustainable Social Impact

“Why are these orphans living in a dilapidated factory? What’s the difference between me and these kids? Why do these things happen?” These were the questions Stan Lee Tan ’19 asked himself as a fifth-grader after his dad’s job took their family to China. “My primary motivation is to solve for that inequality. Your outcome in life shouldn’t be determined by what country you were born in or what family you were born into.”

That motivation is what drew him to a course called Affordable Design and Entrepreneurship (ADE).

Founded in 2012 by Erik Noyes, associate professor of entrepreneurship at Babson College, and Benjamin Linder, associate professor of design and mechanical engineering at Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering, ADE is an international, experiential social entrepreneurship and design course. It aims to address challenges like air quality, child education, community development, food processing, and global health.

But unlike other business models that attempt to provide solutions for people, ADE designs solutions with people. This partnership between students and stakeholders living in the context of poverty allows for the co-creation of relevant and sustainable solutions.

In this sense, ADE mirrors other Babson courses that swap lectures for hands-on experiential learning. But in other ways, ADE takes a drastically different approach.

As a founder-less model, ADE democratizes the business experience, creating more opportunities for collaboration and learning. “It’s not one person with an idea carrying it across the finish line,” explains Craig Bida, Babson adjunct lecturer and senior fellow in social innovation. “It’s about creating the maximum impact for the community, community stakeholders, collaborators, and the students themselves.”

Learning to Slow Down

“ADE focuses on learning to have impact by working to have long-term impact,” begins Bida. “That means having the time needed to have impact and to be reflective, thinking carefully about what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. That’s what gets us to a bigger, better place in the end.”

Irene Laochaisri ’17 notes that the course taught her to include “give things time” alongside “bias toward action” and “resilience toward failure” in her entrepreneurship toolbox. But it wasn’t easy getting there.

“After a few months, I thought ‘What have we done? I don’t see any evidence of us progressing forward,’” said Laochaisri, cofounder of InsightPact. Initially she looked for something tangible to point to, like investment money, to measure success. But ADE helped her shift her mindset. “It takes a really long time to know if something is succeeding or failing. A semester is hardly any time compared to what it takes to bring about meaningful change.”

It’s an important message for students to hear, says Bida. “Failing fast and not worrying about what gets broken doesn’t work when you’re impacting people’s lives.”

“What’s at stake is the livelihood of a community,” Laochaisri emphasizes, referring to an ADE program still operating in Coahoma County, Miss. “You’re making promises to governors, high school students, teachers, artists, activists, and entrepreneurs living in one of the most racially divided, poorest areas of a country. They’re volunteering so much of their time to co-design solutions, you have to deliver on promises. There’s very little room to fail.”

The Power of Co-Creation and Collaboration

ADE also helps students understand the challenges related to meeting the daily human needs faced by a majority of the world’s population. “With social impact projects, the first obstacle you have to overcome is the cultural barrier—to understand your perspective is not the superior perspective,” explains Tan.

That’s where the importance of co-creation and co-design comes in, with communities guiding and shaping the solution. Understanding stakeholder needs and challenges, Bida says, is at the core of the course.

“Communities want more than monetary aid,” stresses Tan. “You need to be connected to people, to real faces and real projects. It’s hard to be passionate about something that’s just numbers.”

“It’s about ‘how do we realize the mission of the project while also being aware of bigger policy changes that affect the program?’” Laochaisri explains, noting that her group witnessed firsthand the effects of the 2017 education budget cuts on their mobile after-school program venture in Coahoma County. “The classroom environment can sometimes fool you into forgetting that everything and everyone is interconnected.”

Collaboration is built into the course by way of the students it attracts. Students from Babson, Olin, and Wellesley College take the course; this year, students from Boston College are participating, too, through a research collaboration. Having students from multiple institutions brings together different perspectives and ways of thinking. Collaborations also occur between students and a community of faculty, ADE graduates who serve as advisors, guest lecturers, and collaborators from the business, social enterprise, and nonprofit space.

Measurable Impact

“Women-owned small businesses in Ghana have increased their incomes, and local organizations in Coahoma County, Mississippi, are running a mobile after-school program to enable creative self-expression and hands-on skill development for youth ages 12 to 18,” shares Bida.

“ADE allows us to see impact in communities,” notes Laochaisri. Some students even choose to do summer internships in the communities in which ADE ventures are operating. “It gives you an awareness of how you fit into a much larger system of people who have done a lot of work before you. You see the past, present, and future.”

A New Home for ADE

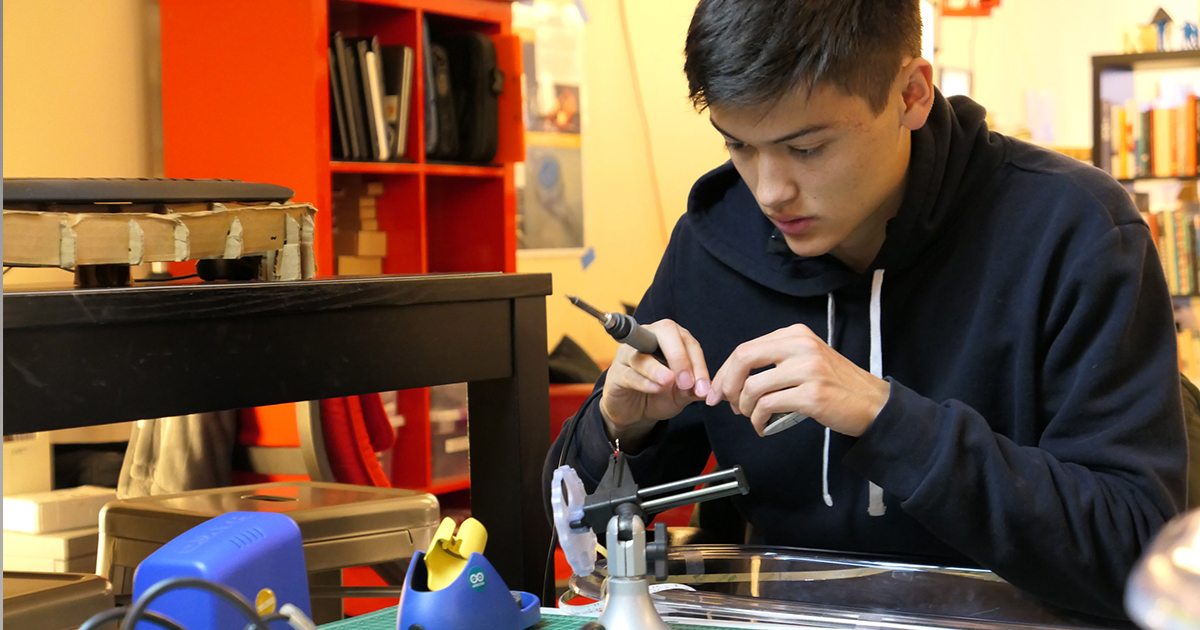

This year, ADE took up residency in the new Weissman Foundry space. The Foundry, an open-door design studio, aims to cut across entrepreneurship, the humanities, and engineering, making it the perfect complement to the course.

Alongside other courses like Blockchain Ventures and Biomimicry Design Innovation from Nature, ADE uses the teaching studio for classes. In the future, students will have access to prototyping equipment—everything from 3-D printers to a full kitchen.

“The space has truly helped create a sense of belonging. People want to be a part of this,” said Bida, noting that one of his students applied to Babson specifically because of ADE. “We’re proud that there are more than 400 former ADE students who have graduated, and many continue to work with people in communities to address challenges endemic to poverty through design and entrepreneurship.”

Posted in Community