Helping Teen Mothers Step Out Of Poverty

In the year 2000, Catalina Escobar had it all: a beautiful family, a promising career running her own international trading company, and a home in Cartagena, a gem of a city on Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

But 2000 was also the year Catalina’s life changed forever. While volunteering in a local neonatal clinic, a newborn died in her arms because the infant’s mother couldn’t afford a $30 lifesaving medical treatment. That same week, Catalina’s own toddler passed away in a tragic accident. Rocked by these painful losses, Catalina channeled her grief into action.

The problem that would become her life’s work was crystal clear. Cartagena had the highest infant-mortality rate in Colombia at more than 48 deaths per 1,000 live births, and 30 percent of the babies born in Cartagena had teen mothers.

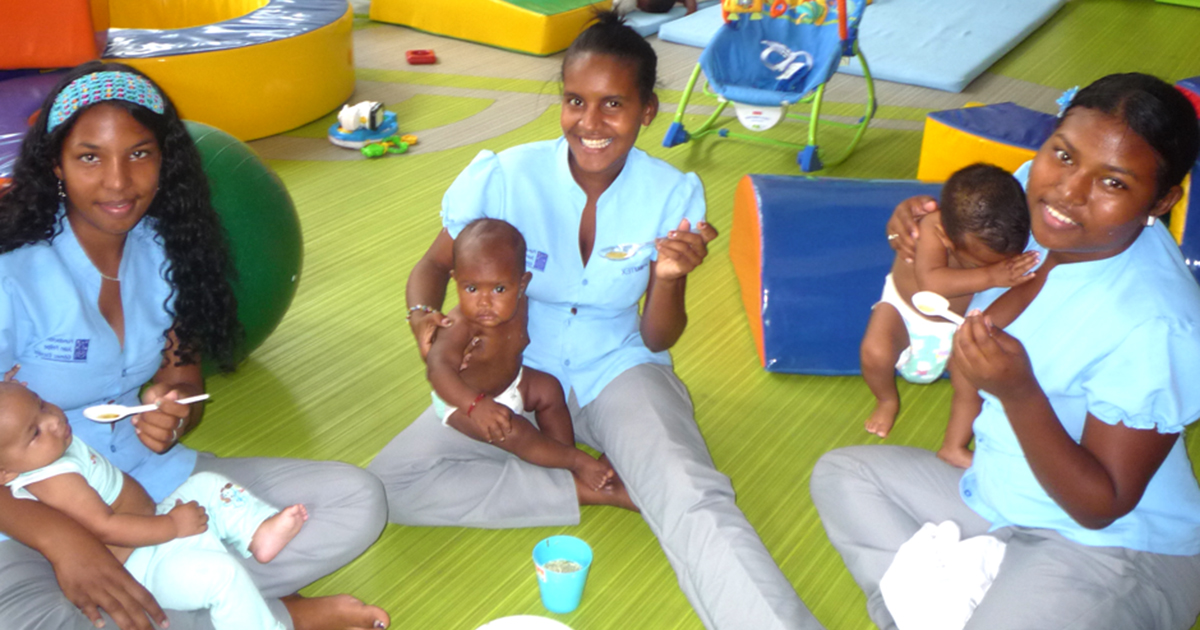

Infant mortality and teen pregnancy fuel a cycle of poverty that Catalina is determined to break. In 2002, she opened the Juan Felipe Gómez Escobar Foundation (JuanFe), named in honor of her son. Since then, Cartagena’s child-mortality rates have dropped 81%, and more than 3,000 teen mothers have carved paths out of poverty. In 2015, the World Economic Forum recognized Catalina as the Social Entrepreneur of the Year, and she received the Community Changemaker Award from Babson College.

Tell us about Cartagena’s teen-pregnancy problem.

Catalina Escobar: Every year in Cartagena, 5,000 teen mothers get pregnant for the first time. It’s not unusual for them to have half a dozen partners in their lifetime and seven, eight, or nine kids. I’ve even met a 26-year-old grandmother. It’s devastating.

When a poor girl gets pregnant in my country, she drops out of school. When she drops out, she no longer has a place in the economic development pyramid. Chances are high she’s going to get pregnant again and again in the following years. Colombia spends a lot of money financing these issues instead of preventing them.

We recruit girls to our program to help break this cycle of poverty. It is demanding and not easy to get in. Girls must be pregnant for the first time, no older than 19, live in extreme poverty, and know how to read and write. We do a very long, thorough psychological exam with each girl because we only want girls who are strong enough not to drop out. In our model, dropping out is failure. The girls we work with are the best of the best. They come to our facility on a daily basis for childcare, life skills, medical care, education, and job training.

How do you balance the business and hands-on sides of running the JuanFe foundation?

CE: It’s 50-50. We’re a nonprofit but I manage it exactly like a business. I love the numbers. If somebody comes to me with an idea for a new project, I won’t even listen until I can see the numbers. Every Friday, I have a call with my key people in Cartagena to talk about the week. I say “OK, how many kids did you take in this week? Tell me about this girl, tell me is this other girl doing better?”

The other 50% of myself is the loving care for my babies and girls. Since the early 2000s, I’ve worked with more than 3,000 girls, and 76% are working professionally today. We still have challenges and things we’re just taking year by year, but what keeps me going is the girls, their babies, and the impact we’re having on these lives.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve faced?

CE: We’ve worked hard to develop a self-sustainable business model, and we’re starting to scale. We’re replicating the model in Panama, we’re going to try for Bogotá, and after that Mexico, Guatemala, and Chile. We’re very careful about our growth and are working with advisers who are helping us scale in the best way possible so we don’t make mistakes.

How do you measure your impact?

CE: The easy part is watching the official mortality rates drop.

With our teen moms, it’s harder to measure success, so we have a few key drivers. Number one is that for the next seven years, they cannot get pregnant again. I read a study that teen moms have very low chances to become socially productive in the future, but with two or more babies, her chances are basically zero. We take care of the girls and babies, teach them about methods of contraception, and provide education. Right now, 95% of the girls we work with have not had a second baby. And the second key driver for success is education and jobs. Earning money empowers these girls to move forward.

JuanFe has been around for 14 years, so some of the first babies you worked with are teenagers themselves now. What do you see in their generation?

CE: That’s right! It can be easy for outsiders to blame poor people for their poverty; they say they live like that because they want to. I describe the environment as a fish tank, and these people can only do so much with their lives based on what they have available in the slimy fish tanks where they’re raised. So many girls in Cartagena live in poverty and are consequently recruited by the guerrillas, or become teen moms, victims of violence, sexual abuse, malnutrition, or all of the above.

The babies we work with have been born into a different fish tank, and they’re growing up differently.

If you weren’t running the JuanFe foundation, what would you be doing instead?

CE: I can’t imagine my life without this. I know all my girls and hold their babies on my lap, so this is bigger than just my life. We’re helping people and creating impact in the most efficient way, changing other lives and breaking the poverty problem. Just thinking about it makes me so very happy.