What the Future Demands of Today’s Classroom

Last year, the world’s population hit 8 billion people. In 2037, it is expected to jump to 9 billion. By 2050, it will be closing in on 10 billion.

That’s a lot of people, and that large number poses a complicated, daunting question: How will we feed them all?

That monumental challenge hangs over Food Systems: Feeding the Modern United States, one of Babson’s Socio Ecological Systems (SES) courses, which became a requirement for all College undergraduates in 2021. SES courses each focus on a theme—one concentrates on urban environments, for instance, while others deal with climate or water—and are co-taught by two professors: one from the natural sciences and the other from the humanities or social sciences. Students typically take an SES course during their sophomore year.

Food Systems, which focuses on the production and accessibility of food, kicks off by looking at 2050 and those billions of mouths to feed. “You see how vast the problem is,” says Jessica Simon, associate professor of practice in economics and one of the Food Systems teachers.

Throughout the semester, the issue of food is examined from a holistic, all-encompassing panorama, from soil to supermarket to plate. Students look at farming practices and regulations, at the workers who make the food and the consumers who eat it, at the costs of food production on people and the environment, and at how ecological, social, and economic factors intertwine when we sit down at the dinner table.

“The world is changing rapidly. To solve the world’s largest problems, it will require interdisciplinary thinking. The way we build knowledge is not just individuals in the field. It takes a team. This is key to building the entrepreneurial leaders of the future.”

Wendy Murphy, professor of management and associate dean of the Undergraduate School

It’s a complex course. Multiple perspectives are considered, and the consequences of decisions, from those of governments and corporations to those of consumers, are analyzed. “Every decision you make has some sort of impact, some bigger than others,” says David Blodgett, associate professor of biology and the integrated sustainability faculty director, who teaches Food Systems with Simon. “The course shows how all these pieces are linked together.”

This wide-angle, interdisciplinary approach is a hallmark of the SES courses. It’s also a thread that runs through many other classes and programs in both the undergraduate and graduate schools at Babson and is a key component of entrepreneurial leadership. To solve the complex troubles of our world, whether that’s fighting climate change or feeding 10 billion people, one must understand disparate viewpoints and disciplines and work well with diverse groups.

“The world is changing rapidly. To solve the world’s largest problems, it will require interdisciplinary thinking,” says Wendy Murphy, professor of management and associate dean of the Undergraduate School. “The way we build knowledge is not just individuals in the field. It takes a team. This is key to building the entrepreneurial leaders of the future.”

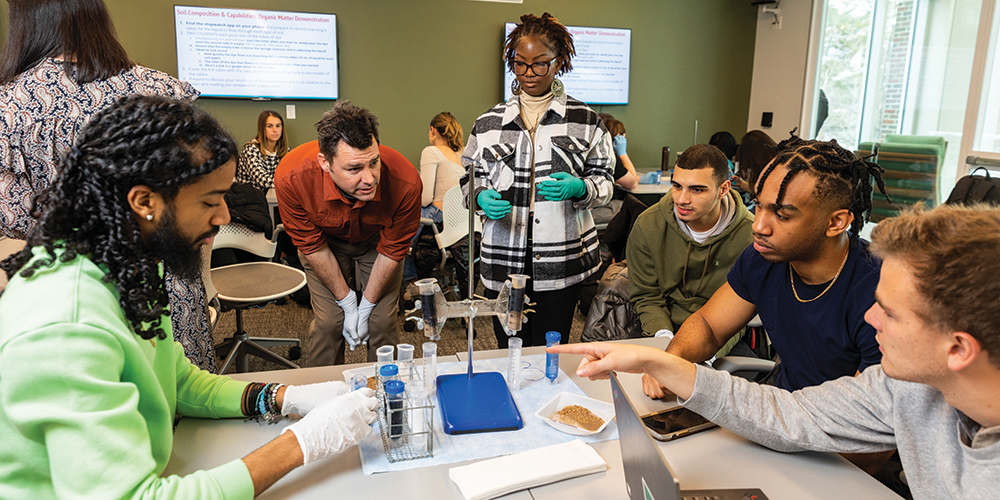

The Food Systems: Feeding the Modern United States course begins with a daunting question: With the world’s population expected to be near 10 billion by 2050, how will all those people be fed? (Photo: Jake Belcher)

Can’t Go It Alone

SES may be a relatively new course, but this interdisciplinary thinking is not new to Babson. “Babson has a long history of what we used to call integration. We were trying to transcend the disciplines,” says Sebastian Fixson, the Marla M. Capozzi MBA’96 Term Chair in Design Thinking, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. “It is an idea that has been here for at least a generation. In some sense, that is part of our DNA.”

The necessity of this interdisciplinary approach becomes apparent once students graduate and find themselves in their careers working on elaborate projects or facing intimidating challenges. To get things done, they often need knowledge in multiple fields or collaboration with people from different departments. They can’t, in short, go it alone. They can’t be isolated in their relationships or siloed in their knowledge. “In real life, problems never come nicely compartmentalized,” says Fixson, also the associate dean of graduate programs and innovation.

Sebastian Fixson, the Marla M. Capozzi MBA’96 Term Chair in Design Thinking, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, and associate dean of graduate programs and innovation (Photo: Jake Belcher)

This is especially true as the world has grown more and more complex. People can’t be expected to keep up by themselves. One person can only know so much about business and technology. “If you can’t collaborate, it is very difficult,” Fixson says. “We need to find ways to combine and integrate knowledge.”

That’s why interdisciplinary programs and courses often emphasize teamwork in situations that mimic the real world. One prominent interdisciplinary endeavor in the F.W. Olin Graduate School of Business is the Babson Entrepreneurial Thought & Action Experience, or BETA-X, a project in which MBA students work in teams to propose and refine entrepreneurial ventures. As they work on their projects, BETA-X teams incorporate insights from eight different disciplines (see sidebar, below).

Another interdisciplinary undertaking is the yearlong Leading Entrepreneurial Action Project, or LEAP, a central component of the MSEL degree. LEAP represents the intersection of two distinct fields: design and entrepreneurship. Students are again placed in teams and work toward producing a venture that is launch ready.

Visit a LEAP course on a typical Wednesday morning in Olin Hall Room 125, a classroom crammed with whiteboards just waiting for ideas and plans to be written on them, and you see eight small teams gathering around tables. “OK, let’s go to work,” says Fixson, calling the class to order. Munching on candy bars for a little energy, the teams huddle together and hash out whatever issues they’re facing, while Fixson and his co-teacher, Edward Brzychcy, an adjunct lecturer in the Management Division, go from table to table offering feedback.

In the graduate school, Fixson says, students are taught how to work in teams and how to give and receive feedback from each other. Typically, they are grouped with people of varied backgrounds. “We are intentional about how we create teams,” Fixson says.

Two Teachers, One Class

Another feature of interdisciplinary courses at Babson is that they are often co-taught by two professors from different disciplines, which brings varying perspectives into the classroom. LEAP is co-taught, as is perhaps the most well-known course offered at Babson—Foundations of Management and Entrepreneurship, or FME, in which first-year undergraduates team up to launch ventures.

All Socio Ecological Systems courses are co-taught by two professors. In Food Systems: Feeding the Modern United States, professors David Blodgett and Jessica Simon take a wide-angle, interdisciplinary approach that’s a feature, not only of SES courses but also of other classes and programs at Babson. (Photo: Jake Belcher)

At 8 a.m. on a Tuesday, the sky brightening over the campus, the co-taught Food Systems class gathers in a Babson Commons classroom. At each table sit two soil samples.

Co-teachers Simon and Blodgett utilize a wide range of materials and activities in the class. That can mean podcasts, videos, news articles, academic papers, simulations, experiments, or even going to the Weissman Foundry and preparing food with the students. “Dave and I are both open to different kinds of materials and seeing how they fit,” Simon says. “It makes the learning more exciting.”

For today’s class, students will be testing two soil samples to see how well they retain nutrients. One sample is rich soil that is representative of regenerative farming techniques, while the other is less healthy soil indicative of industrialized farming. “You want to move your computers out of the way,” Blodgett tells the class. “We’re going to try and do an experiment.”

Vikki Rodgers, professor of ecology, was a leader in developing Babson’s co-taught SES courses. (Photo: Jake Belcher)

Having two teachers in a classroom is a significant commitment for Babson. “It’s challenging to have two teachers in the classroom from a logistics standpoint,” Blodgett says. But, it’s worth it, not only for the students but also for the professors, who are learning from the fields and teaching styles of each other. Blodgett enjoys studying his co-teachers in action. “A lot of times, I’ll watch the classroom,” he says. “I watch the students, how they interact with each other when someone else is teaching.”

Vikki Rodgers, professor of ecology, was a leader in developing Babson’s co-taught SES courses. When she discusses the co-teaching approach at academic conferences, attendees are typically surprised and impressed. “This is unique,” she says. “It’s not offered at other schools.”

Students aren’t accustomed to this type of teaching either. “This is a new way of thinking for them. We are blending the disciplines together,” Rodgers says. “The goal is that they understand the vital importance of bringing different disciplines together to solve problems.”

Rodgers co-teaches an SES course called Prairie Systems with Mary Pinard, professor of English. The professors provide both a scientific and artistic perspective on prairies, a rich, diverse, and stunning ecosystem that is often misunderstood as a barren landscape. “There is something about the resilience of the prairie, the complexity of the prairie, the beauty of the prairie,” Pinard says.

Mary Pinard, professor of English, co-teaches an SES course called Prairie Systems. (Photo: Michael Quiet)

As with Food Systems, Prairie Systems takes a holistic approach to its subject matter, looking at the interconnections between nature and humanity. Class discussions bounce between Pinard and Rodgers, the pair engaging with each other and demonstrating what collaboration between different disciplines looks like. “We hope it is a model for how students can work together,” Pinard says.

It’s a model that students need. They are graduating into a world filled with imposing problems such as structural injustices and climate change.

“Environmental issues often seem dire for the future,” Rodgers says. “I’m worried our students will throw their hands up and say there is nothing that they can do.”

The interdisciplinary thinking displayed in the classroom, however, offers them a way forward, a way to take on intractable challenges, a way to make a real difference in the future.

BETA-X: Seeing How the Pieces Fit Together

Another characteristic of interdisciplinary learning at Babson is that it is often experiential. The Babson Entrepreneurial Thought & Action Experience, or BETA-X, is a good example. In BETA-X, teams of full-time MBA students gain valuable experience by exploring and developing entrepreneurial projects, taking inspiration from initiatives that real-life companies are working on.

Sinan Erzurumlu, professor of innovation and operations management, who co-created BETA-X (Photo: Webb Chappell)

For example, student teams recently honed business concepts in one of three new focus areas of Procter & Gamble: women’s wellness, redefining aging at home, and maximizing mental and physical performance. Procter & Gamble wasn’t directly involved in BETA-X (companies haven’t sponsored any projects as of yet, though they have served as judges of students’ work in the past), but its initiatives provided a crucial context for students to apply their skills.

“Students really understand what we are trying to teach them when we give them an experiential opportunity,” says Sinan Erzurumlu, professor of innovation and operations management, who co-created BETA-X, which launched in 2019. “It creates an active learning environment.”

BETA-X happens independently of any particular class, but as students work on their 14-week projects, they are taking their core courses at the same time. Any insights they learn in a course can then inform their project. “Each course makes an effort to create exercises or assignments that apply to the project,” Erzurumlu says.

By the end of BETA-X, students will have incorporated lessons from eight disciplines—a wide variety that includes everything from strategy to marketing to business analytics—and will have seen the role that each plays in developing a business venture.

“They see how the pieces come together,” Erzurumlu says. “They see all these pieces serve the same goal of exploring an entrepreneurial opportunity and growing that opportunity into a viable business.”

— John Crawford