Women Weigh Risks and Rewards When Faced with Entrepreneurial Opportunity

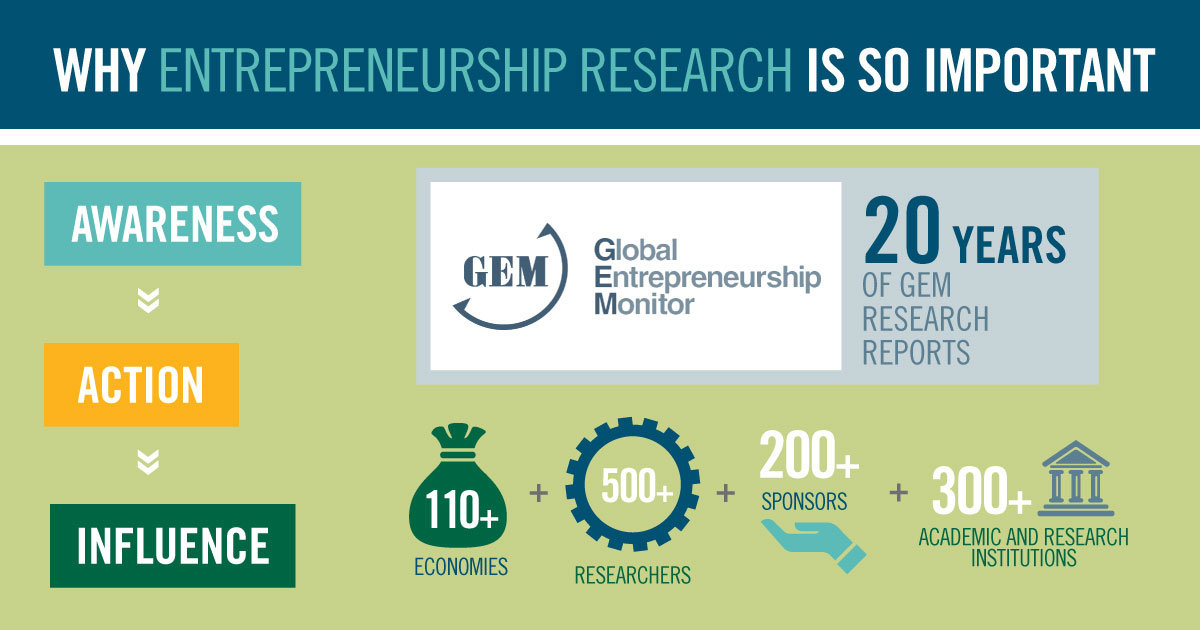

Measures of attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) help us understand how men and women see entrepreneurship differently. The 2017 Babson-sponsored U.S. GEM report finds that 59 percent of women entrepreneurs perceive opportunity, the highest rate ever recorded by GEM, but their entrepreneurial intentions are not trending upward—yet.

The Gender Gap

When it comes to perceived startup capabilities, fear of failure, and entrepreneurial intentions, GEM finds a significant gender gap.

Women’s perceived capability has decreased, making the large gender gap even wider in the past few years.

Women’s fear of failure has been tracking higher than that of men’s for a decade.

And finally, women’s entrepreneurial intentions, or the “intentionally planned behavior . . . to start a new business,” have remained the same for the past few years while men’s are increasing.

When we look at these measures together with women’s increased perception of opportunity, we are presented with a complicated narrative about women’s entrepreneurship. What is uniquely shaping women’s entrepreneurial perceptions and beliefs?

An Ecosystem Problem

The Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership (CWEL) at Babson helps us better understand the implications of the ecosystem.

“Women aren’t less likely to see themselves as entrepreneurs simply because they lack overall confidence. They’re responding to messages they receive from the world around them about who is and isn’t supposed to lead and take risks.”

Susan Duffy, executive director of CWEL at Babson

Given these messages and the observations that women are making about who starts companies, who invests in them, and who receives funding, it is no wonder that their increased perception of opportunity does not automatically translate into increased entrepreneurial intention, especially when they may already have career opportunities that meet their needs. When faced with the realities of entrepreneurship, women may evaluate the pros and cons and simply choose not to start.

Biases and Behaviors

In “A gendered look at entrepreneurial ecosystems,” Babson’s vice provost of global entrepreneurial leadership Candida Brush, and co-authors, explain that there are many aspects of the ecosystem that relate to and can impact self-efficacy, or “the confidence—not the competence—that we have what it takes to be successful.”

Institutions, organizations, and individual players, including role models and mentors, can help or hinder women-led venture creation.

One example of a gendered institution is venture capital financing. In a survey conducted by the Diana Project™, businesses with all-male teams were more than four times as likely to receive VC funding as businesses with even one woman on the team.

There is potential for this to change. New investing platforms designed for women, networks of female angel investors, and VC firms are not only creating access to capital for early- and seed-stage women entrepreneurs, but also educating and developing a cohort of women investors.

This is particularly significant when you consider the impact this new cohort could have on the decision-making process. According to the Diana Project, VC firms with women partners are more than twice as likely to invest in companies with a woman on the management team and almost four times as likely to invest in companies with women CEOs.

Gender comes to life in work organizations as well, through assumptions and behaviors. Even the organizations that are seen as “essential for creating a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem” and critical to the entrepreneur’s journey, such as accelerators, incubators, and co-working spaces, can be gendered.

Brush notes that the vast majority of accelerators around the world are male-dominated: Less than a quarter of participants are female.

Fortunately, there have emerged new organizations for women entrepreneurs that intentionally build startup environments to develop their self-efficacy by creating community and enabling access to resources and networks.

Women Innovating Now (WIN) Lab® at Babson is an intensive, five-month accelerator program created by CWEL to provide high-growth women entrepreneurs with not only a business curriculum, but also one-on-one coaching and a cohort. With an environment that provides four critical elements—female role models, champions and experts, a low-stress environment, and mastery experiences—WIN Lab® drives self-efficacy.

Finally, we look at the influence of the many players in the entrepreneurial ecosystem on an individual level. One player is the role model.

We know that the stereotype of the entrepreneur is male—”the white guy in the suit or the white guy in the hoodie” in the words of Susan Duffy, CWEL’s executive director—and that this could have a negative impact on women’s perceptions.

As Brush explains: “In areas where the role models are male or have only masculine qualities, women may not perceive that venture creation is possible, and they may have a greater fear of failure or less confidence in their abilities to start a business.” Especially when you consider that the effect of having a role model is more significant for women’s self-efficacy than men’s, female role models become all the more relevant.

Another critical player is the mentor. The mentor, along with other players, can act as a gatekeeper to resources, and here again WIN Lab takes up the baton, through robust mentorship.

Angela Sanchez MBA’11, founder of Artyfactos, has spoken about the tangible benefits of having a mentor when it came to introducing her products to retailers. Thanks to her WIN Lab mentor’s network and introductions, Sanchez’s products are now nationally retailed.

A New Ecosystem for Women Entrepreneurs

We begin to understand the impact that ecosystems can have on women entrepreneurs and their perceptions. Facing gendered institutions and norms, work organizations and environments, and stereotypes, a women entrepreneur could logically choose not to startup.

But, there are reasons to be optimistic. The GEM report notes that women are the majority owners of nearly 40 percent of the approximately 30 million businesses in the United States. Not to mention, the total number of women-owned businesses increased by 49 percent in the last decade. And better yet, there are more investors, accelerator programs, organizations, and support structures than ever before.

If the barriers that women face in the entrepreneurship ecosystem continue to break down, then perhaps women’s perceived capabilities and intentions will finally rise in tandem with their increasing perception of opportunity.

Did you miss Part 2 of our series on entrepreneurship opportunity? Read it here and stay tuned for Part 4.

Posted in Insights