The Fine Print on Job Creators: Part I

Who is a job creator? The term has become a political Rorschach test—it means what the speaker says it means to support his or her policy beliefs. Those who run America’s 8.7 million private-sector businesses are commonly the job creators of political discourse. Within that broadest of definitions, however, there’s evidence to support a plethora of policies.

It’s tempting to conjure an image of a job creator as a gutsy pioneer in the world of commerce. This entrepreneur started a software business that now employs 12,000; that one founded a chain of coffee shops, each employing 25 people; those college friends crowdfunded an innovative product through Kickstarter and grew it to 125 employees before selling the business.

The reality of job creation is both more diverse and more prosaic than that. Instagram had 13 employees and no revenue when Facebook bought it for $736 million. Helwig Carbon Products of Milwaukee had 242 employees in 2012 and sales in excess of $30 million. Both are technically small businesses and both create jobs. One of them was breathlessly praised by the business press, but not the one that made the most money or created the most jobs. Instagram certainly created value for its members (and wealth for its owners), but hidden in the flash of high-tech and startup success stories is a complex, dynamic, and familiar foundation of American job creation.

The People

Private-sector job creation occurs when someone senses demand and builds an organization to fulfill that demand for a profit. They are not achieving their dream alone—they hire people. While certain temperaments are more suited to taking entrepreneurial risk, the fact is that there is no single job creator personality, life story, or circumstance any more than job creators are a particular race, sex, age, or political persuasion.

Peter Drucker says the purpose of any business is to create a customer, and this observation can be applied to the most basic fact of job creation: it is the product of demand creation. People who create demand—with a compelling product, service, or even an irresistible marketing message—create jobs.

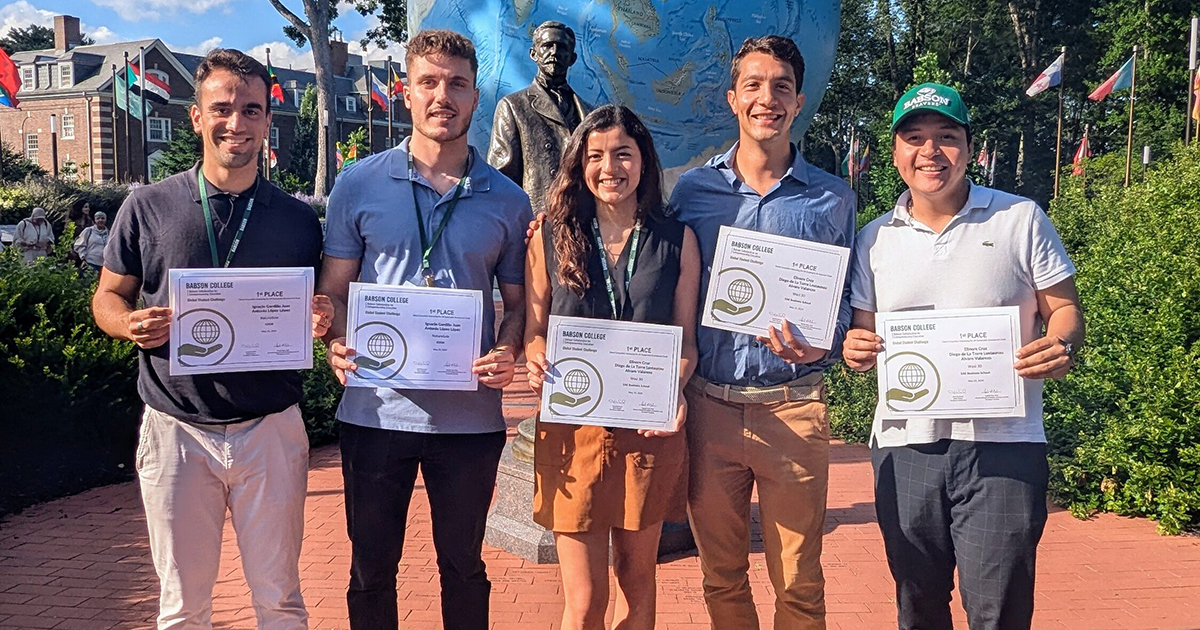

But people, not organizations, are entrepreneurs. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), a Babson-affiliated long-term study of entrepreneurial activity around the world, notes that entrepreneurs who believe they will create jobs in the next five years tend to be innovators and new-product developers.1

Inc. Magazine’s list of top job creators in 2012 spotlights companies and organizations that added the most employees. Interestingly, four of these top 10 job creators are staffing companies Pand outsourcers—in effect, companies whose product is a worker that is then used by a separate organization.

Even in a dynamic economy, the preservation of jobs comes from making a business survive, thrive, and grow. Let’s acknowledge that at different stages of a business, the leadership might be entrepreneurial job creators, and after the fast-growth stage they continue to employ people but aren’t adding many new jobs. They preserve the jobs they’ve created (perhaps we should call them job curators).

Companies large and small are the instruments of entrepreneurial job creation. Babson Professor Patricia Greene, the national academic director of the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses initiative, relates net job growth to the entrepreneurial spirit; in short, new jobs come from new enterprises because their growth depends on expanding business at a faster rate than most long-term businesses. (This is a classic formulation of investment advice; large and stable companies such as those in the Dow Jones 30 don’t grow as quickly as smaller businesses—their attraction to investors is their stability and lower relative risk.)

Lawmakers, economists, and policy wonks are fond of pointing out that most jobs in America are created by small business. That’s mathematically obvious when you consider that the FORTUNE 1000 account for .0166 of the nation’s 6 million businesses and less than 17 percent of American private sector employment (global companies have global workforces). Turnover and job tenure also affect the numbers—job creation means someone got hired; job loss means someone quit, got fired, or got caught up in a business failure.

So who is creating the most jobs? What do the data say? What follows in Part II is a waist-deep wade through which businesses, in terms of industry and size, are creating the most jobs today. In Part III, we’ll see the complications that arise when trying to define entrepreneurial job creation in a dynamic economy, and the effect policy in one area (health care) has on another (job creation).

1GEM US 2010 report: “Twenty-six percent of early-stage entrepreneurs involved in developing innovative products expected to create 20 or more jobs in 2010, whereas only 17.1% of established business owners with new product-market combinations expected to do the same.”

Posted in Entrepreneurial Leadership