Starting but Not Scaling

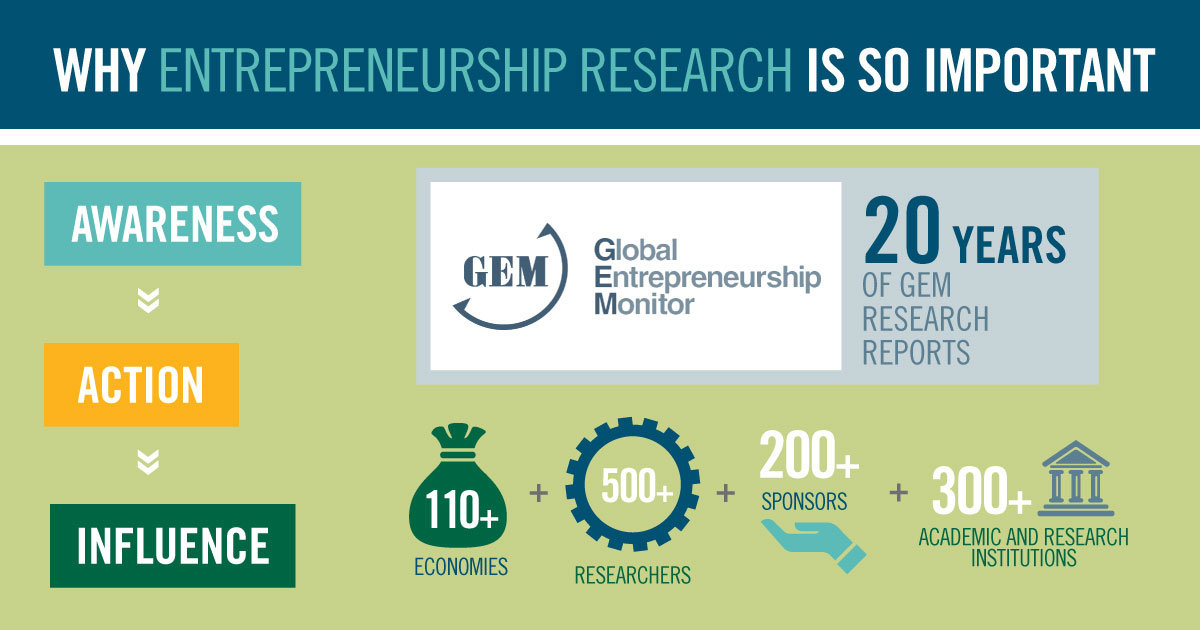

Entrepreneurship that matures into established business ownership contributes immeasurably to society through innovation, job creation, and stabilization of the economy. Even more benefits are yielded when the entrepreneur is of a diverse ethnicity group, according to U.S. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report. But, significant challenges currently stand between entrepreneurship and enduring businesses.

If America Is a Melting Pot, Then Who Is the American Entrepreneur?

The latest Babson-sponsored GEM report points out that the demographics of Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) mimic the demographics of the U.S. population.

According to the findings, nearly one-third of all entrepreneurs are non-White Caucasian, which is generally consistent with the non-White Caucasian percentage of the general population.

Changes in GEM data over time suggest that, as the population changes, so do entrepreneurs. For example, the rate of entrepreneurship pursued by diverse ethnicities was 5 percent higher in 2017 than in 2016.

We hope increased diversity in entrepreneurship will bear out, as non-White entrepreneurship can deliver unique value to society. As the report notes, “Entrepreneurship among non-White Caucasian ethnicities will be important, not only for job creation but also for introduction of unique business concepts and connections to new markets, including international ones.”

We hear about the positive impact of entrepreneurship in this statement—but this impact is predicated on the basis that this entrepreneurship is sustained. For White Caucasians, chances are good. Twelve percent of White Caucasians are starting and running a new business while 9 percent are running established businesses, defined as three and half years or more.

While significant numbers of entrepreneurs are of diverse ethnicities, the numbers drop off when we look at established business owners. Twenty percent of African-Americans start businesses, but only 4 percent are established business owners. We see the same phenomenon with Asian (17 percent start versus 7 percent run established businesses) and Hispanic (12 percent start versus 5 percent run established businesses) ethnicities.

Why Some Ventures Succeed—and Some Don’t

Do these entrepreneurs have the resources critically needed to see a business to maturation? And what are these resources?

Richelieu Dennis ’91, founder, CEO, and executive chairman of Sundial Brands, spoke about the barriers to entrepreneurship when he was inducted by Babson College into its Alumni Entrepreneur Hall of Fame. He distilled the challenges and critical resources down to an acronym: ACE – Access, Capital, and Expertise.

If I don’t have an opportunity to walk into a bank and have equal footing . . . or walk into a supplier and have the same terms as my competitors, I’m not going to be successful.

Richelieu Dennis '91, founder, CEO, and executive chairman of Sundial Brands

Networks are known to be key to business success, providing a variety of resources like collaboration, opportunities to access capital, support, and advice, but diverse entrepreneurs often lack this social capital and are hindered in their attempts to make connections within the business world.

The challenges surrounding financial capital are also considerable, and they begin with the application process.

In the 2016 Small Business Credit Survey Report on Minority-Owned Firms, African-American–owned firms reported more attempts to secure credit than White-owned firms, but the attempts were for lower amounts of financing. And, among those African-American firms that did not apply, 40 percent did not move forward because they were discouraged. This compares with 14 percent of White-owned firms and 21 percent of Hispanic- and Asian-owned firms.

The outcomes of applying for funding are disparate as well. Only 40 percent of firms owned by diverse entrepreneurs with good credit received the full amount requested, compared to 68 percent of firms owned by White-Caucasian entrepreneurs. In addition, the percentage of firms owned by diverse entrepreneurs that received any financing at all was lower than that of other firms.

Not to mention, diverse entrepreneurs are disproportionately hurt by the cost and lack of access to capital. In one staggering figure from the Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs Briefing Series, produced by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, the profitability of African-American–owned businesses is almost three times as likely to be hurt by lack of access to capital as that of White-owned businesses.

Finally, there is expertise. Entrepreneurs of diverse ethnicities may not have the vital relationships they need and face “lack of mentors and role models, difficulty finding good professional partners, and indifference—or even hostility—from business networks.”

These challenges add up to a scarcity of social capital, which can be as crippling as a scarcity of financial capital.

Breaking Down Barriers

How can we better open the door to entrepreneurial growth among diverse entrepreneurs?

Dennis is applying the ACE approach as the strategy behind his New Voices Fund, the $100 million fund he established via the sale of Sundial to Unilever, which seeks to empower women entrepreneurs of color. One of these elements alone will not lead to success—all three are necessary, from Dennis’ perspective.

Similarly, the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses program takes a multipronged approach. Providing a network of business support services, capital, and a business curriculum designed and co-delivered by Babson College, it serves a highly diverse group of entrepreneurs from across the United States, representing different ages, education levels, business ages, and industries. The program enables business owners to identify and take advantage of growth opportunities, and its impact is measurable.

Through exposure to funders, education about financing options, and the development of pitch skills, the program sets up participants to make themselves more fundable. The program’s alumni apply for and receive funding more often, and the numbers only improve over time. Moreover, when they apply, they receive a larger percentage of the amount they request. Alumni also go on to engage with and develop strong business relationships with their banks.

Through peer learning and collaboration, 10,000 Small Businesses creates a network where one may not have existed before. Eighty-eight percent of graduates go on to do business together, and they leverage their new connections for business growth.

Ultimately, the program’s impact manifests in revenue growth, reported by almost four of five alumni 30 months after completion, and job growth, reported by 57 percent of alumni in the same time frame. These are positive results, and these are the very same results that the U.S. GEM report attributes to entrepreneurship when it is successfully sustained to maturity.

From Early Stage to Established

When entrepreneurship thrives among diverse ethnicities, industries, communities, and the economy all benefit immeasurably. When it doesn’t survive, the downside is significant and, as Richelieu Dennis remarked, can manifest as a destabilizing effect.

But with a strategic view and a holistic approach, the challenges that diverse entrepreneurs currently face on their way from early stage to established can be diminished, and we can see these businesses go on to flourish.

Posted in Insights