Moving from Managing to Leading

How many articles in BusinessWeek, Fortune, and The Wall Street Journal have been written on the topic of leadership? How many books? Business people seem to have a bottomless appetite for wisdom about how to lead. Conscientious readers have learned valuable insights about transactional versus transformational leaders, charismatic leadership, shared leadership teams, and the difference between managing and leading.

However, not nearly enough focus has been given to what it takes to make the transition from being an effective manager to an influential leader. This is all the more surprising because most leadership roles are filled from the ranks of high-potential managers. Even the most talented managers often find themselves blindsided by unexpected aspects of their new role.

Even worse, they find themselves feeling out of their depth. Managers who have been especially successful typically “lead from their strengths” only to find their familiar approaches don’t work in this new context. In my experience and research, I have found that understanding and preparing for this transition can help prevent months of frustration and lost momentum, not to mention talent loss.

The Transition

As leadership guru John Kotter pointed out many years ago, effective managers are experts at managing complexity and creating predictable systems. They achieve results by systematically pursuing an often linear path from planning to execution and monitoring, given a specific goal. While success often requires some creativity and flexibility, the best managers are often those who operate with deliberate discipline, including the practice of documenting and learning from past errors. Clearly, this MO ensures positive outcomes, particularly in a context where major challenges are well understood.

In the early stages of the transition, managers often encounter at least one of three distinct challenges.

- New leaders who are accustomed to being given goals from above may look in vain for such guidance in their new roles and find themselves stalled without it.

- New leaders who are used to having someone above them interpret messy data from an ambiguous environment may find themselves terrified at the prospect of having to direct followers onto a less than certain path.

- New leaders who are knowledgeable experts in their domains and thus able to direct others from that base of confidence may find themselves unsure of how to cope with their new dependence on direct reports.

These managerial expectations and habits, developed under the pressure for results and predictability, can act as significant barriers to successful performance in leadership roles. As researchers have noted, leading requires vision and its associated capabilities. These include interpreting the present and predicting likely futures, assessing the organization’s competencies and potential, deciding on a forward direction for the company despite uncertainties and capability gaps, and then mobilizing the employees toward that new destination.

Leadership also requires a mindset that is different from management. For example, leaders tend to focus on reward rather than on risk, facing and managing the latter to achieve the former. As Steve Jobs rapidly deployed iTunes, iPods, iPhones, and now iPads, there were obvious risks to the ongoing success of Mac computers but he obviously kept his focus on the rewards. Managers are often risk averse, taking cautious steps to limit or control risk. Because they must take risks, leaders expect some of their decisions to be wrong and develop a thick skin to tolerate the occasional failure. This is a luxury that most managers cannot afford, so few of them develop the resiliency they will need as leaders.

This comparison of the managerial and leadership roles may explain why some people get elevated to a leadership status that few of their peers and direct reports feel is deserved. Such people escape critique for mediocre managerial performance because they are seen as real leaders. Presumably, such employees have impressed senior leaders with their ability to see the forest for the trees, or perhaps their visionary qualities are felt to be so much more important or unique that lack of management skill is not an impediment to their upward mobility.

The comparison also explains why so many successful managers find this transition challenging. Their prior success makes them expect only more responsibility and complexity, whereas the move to leadership is more like jumping to a new curve altogether. While some get leadership development in programs directed at this specific shift, it is quite common for both organizations and managers to assume that this progression is linear and therefore easier to accomplish.

Making the Transition Mindfully

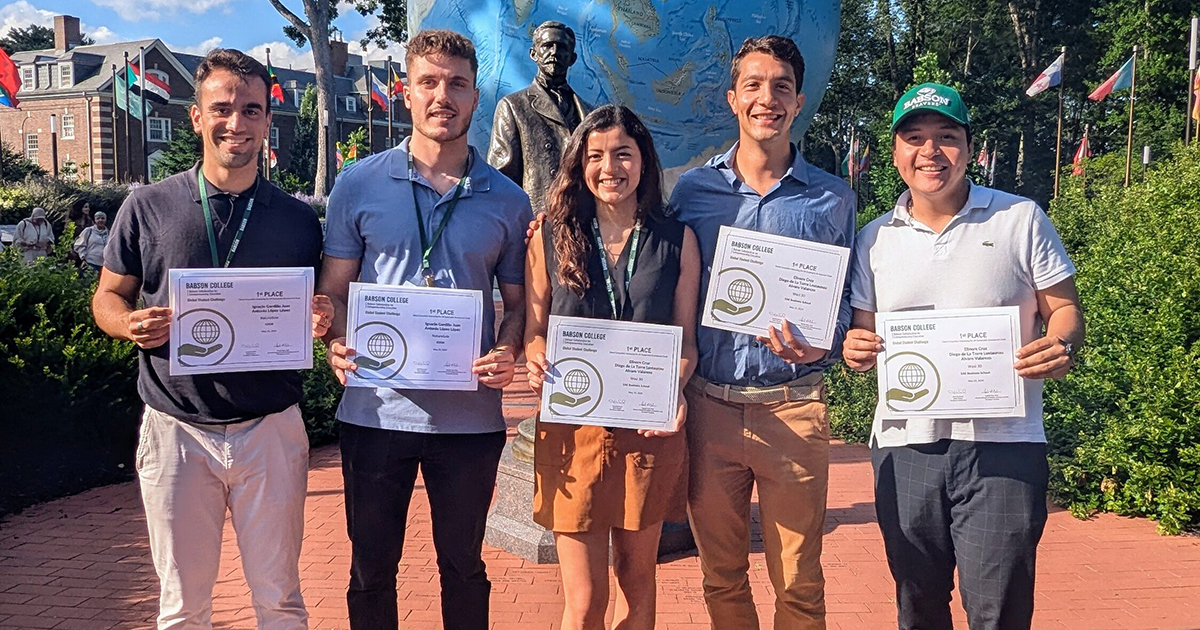

Becoming a successful leader requires mindfulness. Take stock of assumptions about the role and its real and different demands. Simultaneously, consider your strengths and weaknesses and what you really value. One of the major issues we deal with at Babson is how to help our executive participants “leave the old me behind.”

In one of our programs, a newly promoted leader came in focused on how to instill her own meticulous operational mindset into an underperforming employee. She left with a much broader perspective on her new role and its real priorities. This is a critical part of the journey because being the one who ensures results can be seductive, especially when the measures of leadership success are typically much more ambiguous and longer term.

Too many new leaders cling to the old manager mindset for assessing themselves and to the behaviors that deliver short-term results. They don’t realize that they are sabotaging their own leadership by neglecting more strategic responsibilities. Other important aspects of making the transition include, developing both the new skill set and mindset for taking a more strategic role.

The skill set includes strategic analysis of opportunities and threats, grasp of the financial underpinnings of the business, the ability to influence others rather than direct them, and the ability to motivate collaborative effort on behalf of the enterprise. The mindset includes a willingness to take risks to achieve rewards, self-confidence, and trust—in peers and direct reports.

Developing Leadership Talent

A powerful program for leadership development must help participants learn and start the transition both intellectually and emotionally. Exercises, discussions, and self-assessment tools should focus on more than just the new territory into which they are headed and what it will require. It also must explore the challenges of transitioning from where they have been.

Action-learning exercises can have a remarkable impact when they incorporate two dimensions:

- A focus on the specifics of the participants’ own situations.

- Role simulations that stimulate the critical leadership skill set.

For example, we devote significant time to working in small groups on each person’s particular leadership challenge. Through peer consulting and coaching in those groups, the participants practice and acknowledge the value of a coaching style versus a more directive approach to developing others.

Moving from managing to leading should be cause for celebration of both the old successes and the opportunities that those have created. Acknowledging the challenges with others experiencing similar concerns can unfreeze old habits, and provoke new self-awareness and experimentation with new behaviors.

Posted in Insights