Mason Wartman ’10 in front of his wall of Post-it donation notes

Mason Wartman ’10

owner, Rosa’s Fresh Pizza

Mason Wartman ’10 usually runs the register at Rosa’s Fresh Pizza, the shop he opened in the Center City area of Philadelphia this January. He keeps the menu simple: A slice of cheese pizza costs $1; additional toppings are 50 cents each. Sodas and bottled water go for $1.

Wartman likes his post at the register, mainly because he enjoys chatting with customers, learning tidbits about their lives. Most customers stop in at lunch or on their way home after work. Because of the inexpensive price of a slice, homeless people patronize Rosa’s, too. Often Wartman recognizes them. “I would see people on the corner panhandling,” he says, “and then I’d see them an hour later in our store getting a slice.”

Rosa’s, named for Wartman’s mother Rose (“I kind of took some poetic license,” he admits), is modeled after the dollar-pizza joints Wartman had seen pop up all over New York City while he was working on Wall Street. After three years in the city, he had become “a little bored” with the spreadsheet-and-cubicle life. So he hatched a plan to try the dollar-pizza concept in his hometown of Philly. Coming from a family of small-business owners, he also was drawn to the challenge and freedom of running his own shop. “I like the concept of simple businesses that do one thing and do it really well,” he says.

Photo: Winnie Au

While researching the concept, Wartman learned that in New York these shops attract many homeless customers seeking affordable food. So when homeless people showed up at the counter in Rosa’s, Wartman wasn’t surprised.

He was a little surprised, however, one Sunday afternoon when a customer came in and asked if he could purchase a slice for the next homeless person who stopped in. The man said that in Italy many cafes place empty coffee cups on a shelf behind the register to signify that paying customers have pre-purchased coffee for the less fortunate. “Someone can poke their head into the shop and say, ‘Oh, can I redeem that?’” explains Wartman.

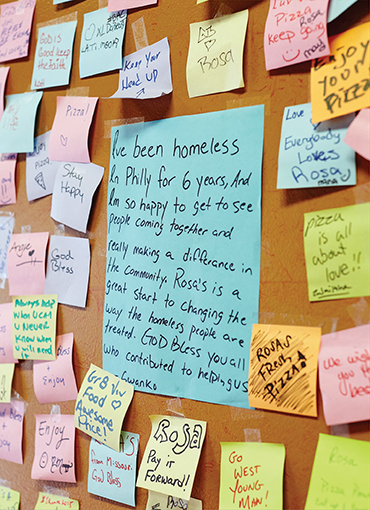

Liking the idea, Wartman started his version of the concept and called it the Little Rosa program. Instead of cups he used Post-it notes, which he stuck to a shelf behind the register, to represent already-purchased slices. Word spread among the local homeless population, and newspaper and TV stories about the pizza shop resulted in people stopping in to donate slices. In the first six months of the program, Wartman gave away more than 5,000 slices. However, he quickly retired the sticky-note system. “The Post-its were covering our kitchen walls, but there’s so much flour in the air that we had to clean the walls,” Wartman says.

Now he tracks donated slices with buttons on the cash register. He still maintains a sampling of the sticky notes—particularly those that include personal messages from donors and recipients—on the dining room walls where customers can see them.

Manning the register, Wartman hears from some homeless customers about how they ended up on the streets. “Maybe they’ve had some drug issues in the past, or an accident at work. They lose their job, they lose their family,” Wartman says. “They know how terrible life can be, and they really appreciate generosity and kindness and the pizza.”

Photo: Winnie Au

By the time the Little Rosa program is a year old, people will have donated about 10,000 slices.

One man stopped in with the news that he had a new job as a bartender’s assistant and told Wartman that the Little Rosa free pizza program helped make it happen. The man explained that the free slices filled him up and allowed him to save $2 a day. After five days, he had saved enough to get a haircut. Within a few more days, he had saved enough cash to buy a thrift-store shirt for his interview. The man’s story taught Wartman how something small, like free pizza, can set a positive process in motion.

But Wartman worries that for most of the homeless customers, “pizza is just a Band-Aid to a lot of their problems,” he says. “A lot of them face drug addiction and problems that pizza isn’t going to fix.” He has been thinking about how he might help people make healthy decisions long before they end up homeless. Recently, he connected with the principal of a nearby charter school to provide free pizzas as a prize for an anti-bullying program. “I hope it’s the start of something preventive,” Wartman says, “so that someone who might have been bullied will stay in school, enjoy learning, get a job someday, and become productive.”

One of Wartman’s current challenges is keeping his business on firm financial footing. The shop is located in a lively area, but his particular block includes multiple vacant buildings, some of which are about to be razed for new development. “In the long term, it’s going to be very good for the city and for me,” he says, but in the meantime he’s brainstorming ways to keep foot traffic steady.

As he approaches his first anniversary in business, Wartman says he loves the “vibrant mix” of customers—both paying and nonpaying—who already have passed through his shop. Watching the community come together over the Little Rosa program has been a highlight of the last year, though Wartman worries a bit about how to keep it going. “Paying customers donate once because they like the idea, and then they keep coming back because the pizza is great, but most people don’t keep donating,” Wartman says. But he’s driven to make it work, one hot slice at a time.

Stephen Popper ’84

founder and executive director, Meals of Hope

Photo: Jeffery Salter

Stephen Popper ’84 at a recent Meals of Hope event

A single conversation with his mother changed Stephen Popper’s life, eventually prompting him to jettison a 28-year business career to focus on feeding the hungry.

“I was in the lumber industry right out of Babson,” says Popper, who lives in Naples, Fla. “I traveled all over the world buying and selling lumber and bringing it to the United States.” In time, he and a partner co-founded their own wholesale lumber company.

Then in the summer of 2007, his mother called to say that she and her sisters had learned about an impoverished school in Haiti and wanted to help its students. If she and her sisters collected food for the children, would Popper figure out how to ship it to them? “Mom, I’ve never shipped food to Haiti,” he told her. “In fact, I’ve never shipped anything to Haiti.”

But his mother persisted. She had heard about events in which volunteers assemble packets of dry ingredients for rice-based meals to send to poor communities in other countries. The meals are later prepared with boiling water, similar to boxed macaroni and cheese.

While discussing his mother’s plan, Popper started thinking about all the people in southwest Florida who could benefit from such meals. The idea began to excite him. Soon he set to work finding food suppliers who would extend him credit and agree to take back any unused ingredients. He secured cafeteria space at a local high school, and then went around to churches and civic organizations, soliciting donations and inviting people to come to the packing event—all while still working his full-time job. “I had no idea what was going to happen,” says Popper.

Photo: Jeffery Salter

Volunteers typically produce tens of thousands of meals in two hours. The meals then go to food banks, which distribute them to food pantries.

In the end, more than 500 people showed up to help, and, in just a few hours, they packed 135,000 meals. He returned to work on Monday brimming with enthusiasm. “I have a smile on my face just thinking about it now,” Popper says. He sent 8,000 of those meals to Haiti, and the rest went to food banks around Naples. Energized by this success, Popper set a goal of packing a million meals in a year’s time, an ambitious target that he and his volunteers easily surpassed—they actually made 2 million. Since that first event in August 2007, Popper’s nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization, known as Meals of Hope, has packed close to 24 million meals.

Photo: Jeffery Salter

Popper and his partner sold their lumber business in 2012, so now he works full time at Meals of Hope. “I have a very supportive family,” he acknowledges. “It definitely helps that my wife also works.” He has evolved into a passionate advocate on the topics of hunger and poverty. “Hunger is a silent epidemic in the United States,” he says. “People don’t realize how pervasive it is. There are school systems that try not to do testing on Mondays for the sole reason that there are kids who haven’t had enough to eat over the weekend, so they’re not able to concentrate and put forth their best effort.” Even in Naples, a relatively affluent community, 64 percent of school children are eligible for free or reduced-price meals, Popper says. He adds that as baby boomers age, “senior hunger is one of the fastest-growing areas of concern in the United States.”

Popper also learned that food banks want a variety of healthy, tasty options, so he began developing other dry meals that could be prepared with boiling water. Current offerings include beans and rice, macaroni and cheese (which Popper taste-tested on his children), a soy “chicken” and rice dinner that includes freeze-dried vegetables, and a Tex-Mex, taco-seasoned rice meal. All four options provide 21 vitamins and minerals and 12 grams of protein per serving, which makes them appealing to food pantries seeking meat alternatives.

Photo: Jeffery Salter

In addition to being nutritious and affordable, all the recipes are designed to be packed by volunteer groups. “Quite honestly, it would be cheaper for us to pack in a factory,” Popper says. “But if we do that, we lose the hands-on approach, and we’d literally lose all our funding.” Meals of Hope receives no government money; it operates solely on private donations. Each packing event is paid for by the participating organizations. Groups such as businesses, civic organizations, churches, and schools agree to donate 22 cents per meal to cover costs, and then volunteers don hairnets, apply hand sanitizer, and work in assembly lines to pack the meals. They measure ingredients into plastic bags, weigh and seal the bags, stamp them with a lot number and expiration date, and then box up the finished product. The volunteers typically produce tens of thousands of meals in just two hours.

Popper runs these packing events in Florida and across the country. They feature music and lots of cheering, creating a festive atmosphere. “People walk away feeling like they’ve really accomplished something,” he says. “When you write a check to a charity, you know it’s the right thing to do, but sometimes your warm and fuzzy feeling lasts only as long as it takes the ink to dry.”

Photo: Jeffery Salter

Although he has switched fields, Popper says he still relies on lessons he learned 30 years ago at Babson. “I try to use a business model in running a nonprofit,” he explains. His organization produces a profit and loss statement for every packing event, and he uses the same skills he honed in buying and selling lumber to purchase pasta and other ingredients.

Popper recently decided to expand the mission of Meals of Hope by opening a full-service food pantry in the Naples community of Golden Gate, a so-called “food desert” where fresh and healthy foods are difficult to find. The pantry will offer a range of staples, including produce, meat, dairy products, and dry goods.

Looking back, Popper is glad he had that conversation with his mother. He often thinks about 2007, when he met his original goal of packing 1 million meals. “People would come up to me and say, ‘Are you going to stop now?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely not. Too many people don’t have three meals a day and are now relying on the food we produce.’”