Edlyn Wang '12 at a subway station in New York City

The Dancer

On a sunny afternoon in Manhattan, Edlyn Wang ’12 looks for a bench. She walks in Central Park, which is overloaded with people clamoring for green and open space.

Passing a violin player, caricaturists, and men offering rides in rickshaws, she finally finds the perfect spot to watch the world go by. A few benches down, a man sings and strums a guitar. “I like to people watch and guess their stories,” says Wang, 23, as a never-ending parade of horses and buggies trots past, the drivers pointing out sights to their passengers.

Photo: Winnie Au

Edlyn Wang ’12 has a full life in New York. She dances, dines out, and works a rewarding job. But Wang wonders what more she should be doing with her life. “I want to do cool things,” she says.

Wang has just come from one of her favorite restaurants, The Meatball Shop, which as the name suggests serves not much more than meatballs. Now she sits in Central Park, one of her favorite places, thinking about a dinner party she’s hosting that evening in her apartment.

Such is how Wang spends her free time in New York City. Since moving here shortly after graduation, she has surrounded herself with good friends, good food, and good times. She works for Ross Stores as an assistant buyer in ladies sportswear, a job she enjoys, and the former president of the Babson Dance Ensemble still rehearses and performs as part of a dance company in the city. “It’s like BDE all over again,” she says. New York has presented her with challenges, but, all in all, she is a young person, barely two years out of college, who is enjoying herself in the greatest city in the world.

However, something gnaws at Wang. She thinks of her life now, and as fun as it is, she wonders, is this it? Should there be more? Should she be trying to make a greater impact on the world in some way? She’s not sure how to answer these existential questions. Through the years, school gave Wang structure, and she always did exactly what she was supposed to do. She went to high school, worked hard, and was accepted into a great college. Then she worked hard in college, graduated, and found a great job. “Now what?” she says. “You’re forced to figure it out. There’s no other guidance.”

Photo: Winnie Au

Edlyn Wang ’12

Just moving to New York, so big and amazingly expensive, was daunting for Wang. She and her four soon-to-be roommates (three of them Babson alumni) struggled to find a place to live. “I was so scared when I graduated because I felt like I was being thrown into unknown territory,” Wang says. “But there is nothing you can do to be prepared for the real world.”

She and her roommates found a 25th-floor apartment in Lower Manhattan’s Battery Park neighborhood, but it didn’t have enough rooms for the five of them. So at the cost of several thousand dollars, they put up temporary walls to divide rooms. That solution worked, except privacy became nonexistent. Late at night, the roommates couldn’t even type on a laptop without disturbing each other. “You could hear everything,” Wang says. “It was ridiculous.” Striking a few months after they moved in, Hurricane Sandy brought even more serious inconveniences, knocking out power in their building for weeks. Wang became an exile forced to crash on friends’ couches. She kept a suitcase of her clothes at work.

Last year, Wang and three of her remaining roommates (the fourth left New York for Boston) moved into a third-floor walk-up in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen, a once-gritty neighborhood that’s gentrifying. ln her modest bedroom, Wang hung two class portraits from Babson over her bed. “It feels like a dorm,” she says. “We’re all best friends.” Wang hopes they stay put for a while, but she knows that inevitably their rent will go up or one of her roommates will leave, so she could be on the move again.

Like many 20-somethings, Wang also is dealing with the D-word—dating—a different experience in a city of 8 million people. “There are so many choices,” she says. “No one wants to settle for anybody.” Wang had been seeing someone recently, but the young man was much more serious about the relationship than she was. He thought the couple might actually be married one day. That wasn’t to be. After six months, Wang let him slip away. She would love to settle down and have children one day, but, unlike other women she knows, Wang isn’t afraid of being alone now in her life. “It doesn’t bother me,” she says. “I have great friends.”

Photo: Winnie Au

Edlyn Wang ’12

Wang and her friends spend many bustling nights in bars and restaurants, but there are quieter moments, too. Like her, Wang’s friends are trying to hash out the weighty questions that nag them. Late at night in their apartment, they talk of work, love, and life. “What makes us happy?” they ask each other. “Does money make us happy, or what we do? Are we happy with work? Do we want to start our own business?” Wang always wanted to work in fashion, but, while she likes being a buyer at Ross, a job that takes her all around New York’s Garment District to visit vendors, she wonders if it’s something she wants to do the rest of her life. Should she think bigger, maybe try to change the world in some way? She volunteers at a soup kitchen, but she feels she should do more. But what?

To inspire herself, Wang keeps a journal in which she writes personal goals. “To live every day with intention and purpose,” reads one. “To never settle for anything,” reads another. Dance also provides inspiration. When she left Babson and the BDE, Wang felt the loss of dance in her life. “I felt like I wasn’t myself anymore without dancing,” she says. Last year, she joined DanceWorks New York City, and every Wednesday and Thursday night she’s at the company for rehearsals. Wang says that she’s not always quick to share her feelings with others, but dance offers a way to express herself. “It’s raw, beautiful, and real,” she says. “The dance is my life.”

For now, the big existential questions in Wang’s life remain unanswered. As she sits on the Central Park bench in the late afternoon, she has a different issue to figure out: What should she make for the dinner party tonight? It’s at 7, so she needs to hustle off. As the horses and buggies and the many people of New York still parade before her, she stands up and heads to the grocery store. What she’ll eventually make for dinner is still undecided, but she knows that sooner or later, inspiration will strike her.

The Entrepreneur

For Dan Ustayev ’12, the second floor of the Newton Free Library is a sanctuary.

Every afternoon, the 24-year-old takes an hour out of his workday for a bit of peace. Sometimes he stops at a coffee shop, but often he comes to the spacious library. “It keeps me tranquil,” says Ustayev, who doesn’t look at his phone during these visits but instead grabs books and magazines and plops himself in a comfy chair. In front of him, a large window looks out on a busy street and cemetery. A nearby sign asks for quiet.

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Dan Ustayev ’12 has opened two burrito restaurants, one in Boston and one in Newton. He enjoys being the boss, though the eateries tire him out and leave him with a meager social life. “Not every person can do this,” he says.

Ustayev needs this respite because the rest of his day is one long, hectic haul. He is the founder and owner of Los Amigos, a burrito restaurant with two locations, one in Boston’s West Roxbury neighborhood and the other in Newton’s Newtonville section. At Babson, he had considered going into finance but decided that he wanted to be his own boss, just like his father, who owns a successful pizza shop. “You’re doing your own thing, instead of following the corporate world,” Ustayev says.

Being your own boss, though, comes at a cost. “It basically takes up my life,” he says. “I sometimes feel like I’m missing out on my early 20s.” The restaurants are always on his mind, from the moment he wakes up at 8 a.m., looking at his phone to see if any workers aren’t coming in, or if the refrigerator is malfunctioning, or if anything else could possibly be wrong, until 10:30 p.m., when he finally drags himself home, the workday mercifully ended unless he still has payroll or scheduling to finish. That’s the way it goes, day after day, 70 to 80 hours a week.

Photo: Pat Piasecki

His social life is lacking. The early 20s can be a responsibility-free time, perfect for hanging out and happy hours, for late nights and late weekend mornings. Not for Ustayev. “I don’t tend to go out,” he admits. “I’m just too tired. I’m on my feet all day.” Ustayev went to the movies on Christmas because it’s one of the four days all year his restaurants are closed, but otherwise he can’t remember the last time he did that. When friends call, saying they’re headed to the bar, Ustayev usually begs off. On the rare times he joins them, he’s always watching the clock, making sure not to stay out too late.

He still lives at home with his parents in Newton, but that doesn’t bother him. Other than sleeping, he doesn’t spend much time there. “Why move out?” he says. “My home is my restaurant.”

Then there’s the matter of his girlfriend. She wants to spend more time with Ustayev, but there’s not more time to be had. She’ll hang out at Los Amigos, but sometimes, just sometimes, she would love to go out, the two of them together, to a restaurant where Ustayev is being waited on and not the other way around.

Ustayev’s entry into the crazy world of restaurant ownership happened his senior year at Babson, when he opened his first location in West Roxbury and his life promptly became a blur of school and work. Employees constantly quit on him in those early months, and he admits that his management of the restaurant was a bit disorganized. About six months passed before he finally had a solid group of employees he could count on. “It was stressful,” he says. “I didn’t know what I was doing. That may be why people were quitting on me.” As someone who isn’t an extrovert, Ustayev at first felt unsure of himself as a leader. “It’s not easy to be respected if you’re quiet,” he says. “I’ve learned I can direct people and motivate. I didn’t know I had it in me.”

Photo: Pat Piasecki

The West Roxbury Los Amigos now runs efficiently on its own, so Ustayev spends most of his time at his Newtonville location, which opened last December. Every day he arrives at the restaurant after first buying fresh produce at the Restaurant Depot. He and his staff, wearing green Los Amigos T-shirts with the words “eat more burritos” written on the back, prepare to open the doors at 11 a.m. Vegetables are chopped, salsa is made, and beans, rice, and meat are cooked. As customers file in, Ustayev floats between the cash register and the prep line with its bins of guacamole, sour cream, and cheese. He calls out orders, stirs big pots of rice and beans on the stove, watches the burritos and tacos being put together, and dashes across the street to the bank if the cash register needs dollar bills.

The pace is fast, especially if nearby Newton North High School is in session, as a horde of hungry teenagers will descend upon the restaurant. Once the lunch-rush dissipates, Ustayev seeks the solace of the Newton library. “It’s not just physically exhausting, but it’s mentally exhausting,” he says. “My mind is moving in a thousand different directions.” Ustayev is always thinking of the customers and whether they’re enjoying the food and service. He knows that just one unpleasant experience can cause bad word of mouth to spread. “Customers are my bosses,” he says.

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Dan Ustayev ’12

Looking back on the two years that have passed since graduation, Ustayev knows he has learned a lot, though some lessons he wishes he had learned sooner. “I wish I had known how time-consuming running a business is, and how hard it is to find good help,” he says. He suggests that young people find mentors. Luckily, he had his dad, a fellow restaurateur, to give him advice. “It’s tough out there by yourself,” Ustayev says. “The real world is not easy.”

But despite all the sacrifices he makes to be an entrepreneur, all the exhausting days and missed good times with friends, he still believes owning your own place is worth it. He finds satisfaction in feeding his customers, and he hopes to open more Los Amigos in the future. “This is my baby,” he says, gesturing all around him inside his Newtonville restaurant. “I take care of it.”

The Biker

Nik Beisert ’11 sits outside at a table at Google headquarters, otherwise known as the Googleplex, in Mountain View, Calif. Ever-present tourists wander around the sprawling campus, and families near Beisert are playing volleyball on the quad. As usual, the sky is clear. “The weather is always perfect,” Beisert says. It’s a Sunday, and he’s here to do a little work and partake of the many amenities Google offers its employees. He’ll hit a company gym, eat free food in a cafe, and do some laundry.

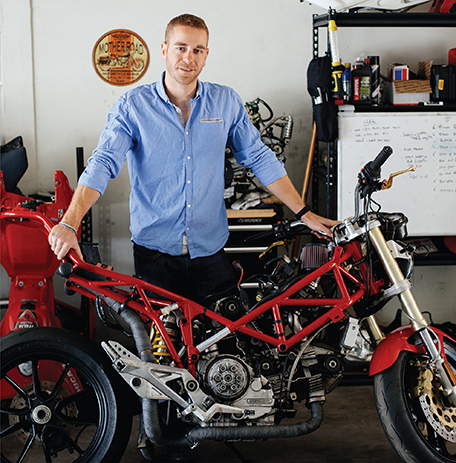

Photo: Annie Tritt

Formerly of Dedham, Mass., Nik Beisert ’11 now lives in San Jose, Calif., and likes working on motorcycles in his garage. “The move here triggered a lot of things for me,” he says.

It’s an enviable place to work, but the 25-year-old hadn’t planned to land a job at the tech giant and move to California. He had been living in Dedham, Mass., engaged to his long-time girlfriend, and working at PricewaterhouseCoopers. At the time, he hadn’t been out of Babson a year yet, but his life seemed set. His career trajectory at PwC looked good, and on the side he had a startup, Earthworm Soil Co., that he found challenging but rewarding. Beisert was, in short, a young man who was content and in love. But then in early 2012, Google sent him an email. His life would soon be upended. “Everything was flipped on its head and went through a hurricane,” Beisert says.

At PwC, Beisert worked with mergers and acquisitions, performing due diligence before purchases and then helping companies integrate their operations after one acquired or merged with another. As for Earthworm, Beisert started the company while at Babson, buying an old garbage truck and collecting food waste to be made into fertilizer. The truck proved unreliable with frequent breakdowns, and he once was pulled over and given a safety inspection. The truck failed. “When I look back, I think, how was I crazy enough to do that?” he says. Eventually, he sold the truck and stopped collecting waste, focusing instead on helping farms set up their own fertilizer-making capabilities.

The Google email came as a surprise. The company was looking for someone with operations experience who spoke Portuguese (Beisert is Brazilian). For a year Google had been looking to fill a position in People Operations, or what most companies would call human resources. Google contacted Beisert after coming upon his LinkedIn profile. “The guy emailed and said, ‘You want to talk?’” Beisert recalls. “I said, ‘Sure, let’s talk.’” Beisert assumed the conversation would be casual, a getting-to-know-you chat, but the interviewer peppered him with brainteasers. A second interview, conducted in Portuguese to test Beisert’s knowledge of the language, followed.

Photo: Annie Tritt

Up to this point, Beisert was hesitant about these interviews. He liked PwC, and he thought his odds were long at ultimately landing the Google job. But then he was flown out to Mountain View for on-site interviews. The campus, to put it mildly, impressed him. “That was a mind-blowing experience,” he says. Beisert’s hesitancy faded, and after yet one more interview and an offer review process, he was hired. Leaving behind his fiancee in Dedham, he moved to California in June 2012 and found a place to live in San Jose with a garage, which was critical. Beisert is a car and motorcycle guy, and he likes space to tinker. “I always need to be doing something with my hands,” he says.

The cross-country move behind him, Beisert was excited for the new chapter in his life. That is until he began at Google. Introduced to his co-workers, he found them to be a quiet, introspective group to which he couldn’t relate. He suddenly felt alone, a stranger in a strange place. “It was one of the worst feelings in my life,” he says, thinking to himself, “What am I doing here?” But what seemed unsettling became an opportunity for self- discovery. His entire life, Beisert had surrounded himself with a community of friends. He was an extrovert who thrived in the company of others, or so he thought. “Being out here forced me to be by myself,” he says, and, to his surprise, he realized that he liked it. Maybe he wasn’t such an extrovert after all.

Beisert did meet like-minded people in the coming months, and a new circle of friends gradually has grown around him. They go to concerts and barbecues, take trips to Las Vegas. But Beisert also spends a lot of time by himself, particularly in his garage working on a new venture. Beisert ended Earthworm Soil Co. when he moved to California, but he now wants to start a business that sells kits for making custom-built motorcycles. He currently is building a prototype, so, after coming home from Google, he puts in an hour or two in the garage, stopping work at 10 p.m. so as not to disturb the neighbors. On weekends, he works longer stretches, as many as eight hours at a time. “Who knows what it will turn into?” Beisert says. “I would be happy with a steady income building bikes all day.” Not that he’s leaving Google any time soon. After the rough start, he has grown close to his colleagues, and the work, which involves developing and improving HR processes, is fulfilling.

Photo: Annie Tritt

Nik Beisert ’11

All this change—the new job, the new friends, the bike business, the self-discovery—was happening as Beisert’s wedding date grew closer. He had known his fiancee since high school, and he cared deeply for her, but doubt had crept into his mind. He had built an interesting life in California. Would marriage hamper that? The wedding was set for August 2013, but by early 2013, he felt anxious and uncertain.

During Easter 2013, Beisert traveled to Brazil to spend time with family. His impending marriage was a frequent topic of conversation. What would you do, he asked family members, many of whom had gone through divorce. His aunt advised him: “Nik, you should focus on yourself. Do what you want to do.” His brother, on the other hand, warned caution. “I saw you two as the perfect couple,” his brother said.

The issue came to a head on April 1, the wedding about four months away. Beisert wanted to explain his feelings in person to his fiancee, but when the couple was chatting on Skype, talk turned to the wedding. Beisert blindsided her, telling her his doubts, how he wasn’t ready for marriage and wanted time alone. He was honest but blunt. “I really regret the way I went about it,” he says. “I was too abrupt and detached. It was destructive.”

The wedding was off, but Beisert still wanted his fiancee in his life. After such a painful conversation, though, how could their relationship go on? How could he heal the damage he had done? It has taken months, and he still feels guilty about the hurt he caused, but the couple seems to be working through the fallout of that Skype conversation. “I think it’ll work out,” he says. “I ran a huge risk of losing her.” And so, as he sits at a table on the Google campus, the tourists milling about, Beisert reflects on how the tumultuous life set in motion by that momentous email has finally calmed down. He’s up for a second promotion at Google, he’s looking to buy a house, and he’s committed to the woman he loves. Above him, the California sun shines down, as it almost always does.