After moving away in search of a cosmopolitan life, Colleen Heidinger ’06 now lives in Buffalo, New York, where she grew up. She is outside the building she recently bought and is renovating.

As a teenager living in Buffalo, New York, Colleen Heidinger ’06 longed for the day when she could leave. She refused to apply to any nearby colleges. “I was adamant that once I left, I’d never come back,” she says. Buffalo felt too sleepy for an ambitious high schooler who longed for big city culture and a challenging career.

After graduating from Babson, Heidinger headed to New York City to work for a small consulting and money-management firm that specialized in socially responsible investing. But she decided the fit wasn’t right, and within six months Heidinger accepted a position with FremantleMedia, a global television production company responsible for shows such as American Idol, The X Factor, and The Price Is Right. Her job involved supporting business that was generated by programs such as product placement. “The Coke cups on the desk that Simon Cowell and the other judges drank out of on American Idol? That was a deal that our team did,” Heidinger says.

She spent six years with the company, first in New York and then, looking for a warmer climate, in Santa Monica, California. Heidinger next took a special-events position with DreamWorks Animation, arranging movie premieres, global film launches, and company appearances at the Cannes Film Festival and trade shows. “It was an incredible company to work for, but I didn’t care much about the work I was doing,” she admits. “I was never star-struck. That made the 16-hour days really difficult.”

As her 30th birthday approached, Heidinger decided to fulfill a longtime dream by taking a three-week trip to Kenya. She went on safari and then spent a week in the slums of Nairobi, where she helped break ground for a women’s clinic and volunteered in an orphanage for children with addictions. The experience led her to question her career. “This world is so crazy. There are so many people in need, and here I was working in this posh job—but I was not helping anyone,” she recalls. “I was just making the wealthy wealthier and celebrating celebrities who already had everything they needed.”

At the end of her trip, she returned to California and resigned from her job. But perhaps even more surprisingly, she also realized that she wanted to break the pledge she had made as a teenager and head back to Buffalo. Her periodic trips home had intrigued her. She was discovering new restaurants and development in old neighborhoods, and Yahoo had opened a data center and customer-care facility. “More and more, you’d hear that some classmate from high school had moved back,” Heidinger says.

Around Labor Day in 2014, she packed her Mini Cooper and headed east, uneasy that she was moving back in with her parents and had no job or health insurance. But just a few months later in March, she was hired as director of special events and programming for 43North, a position that means serving as one of Buffalo’s chief cheerleaders.

In 2012, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo had unveiled the Buffalo Billion project to spur economic growth and job creation in the region. One of the initiatives included an annual $5 million business-plan competition that requires winning companies to move to Buffalo and stay for at least one calendar year. Heidinger’s employer, 43North, runs the competition, now in its fourth year. Each October, eight winners are selected and must establish operations in Buffalo by January 1. Heidinger helps employees of those companies settle into the Buffalo area and arranges entertainment itineraries that companies can use to impress important out-of-town visitors. “We recognize that if companies don’t love Buffalo, they’re probably not going to stay,” Heidinger says. “I do anything I can to open their eyes to what’s going on here and help them fall in love with Buffalo.”

Photo: Matt Wittmeyer

Colleen Heidinger plans to live on the second floor of the building she is renovating and open her own events business in commercial space on the ground floor.

Along the way, Heidinger appears to have fallen in love with her hometown as well. “The cost of living is unbelievable,” she says. “There’s no traffic. We have great dining. We have NFL and NHL teams, we attract all the shows and big bands, and after a night out you’re still able to get home in 12 minutes.”

She recently entered the Buffalo real estate market by purchasing a 1914 building in a revitalized area called Larkinville. She is rehabbing the building, planning to live on the second floor and open her own events business in a commercial space on the first floor. “I often tell kids that I mentor, ‘There’s no better place to fail,’” Heidinger says. “If this real estate project blows up, I didn’t use my whole savings account or sign my life away. If I did this in Greenwich Village, you can bet it would be all my money. If you have an idea you want to test out, or need to hire 20 people, Buffalo is a good place to do it.”

Still, coming home has had its challenges. Heidinger enjoys being part of a small, tight-knit community but notes that dating was tough at times. (She now is seeing “a very great guy.”) She also is grateful for Babson friends scattered around the country, including those in New York City and Boston who give her a regular place to land when she needs a big city fix. “I do need to get out of here sometimes,” she says. “But then I’m very happy to come back.”

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Dan Dalet ’03 co-founded SoloCoco in his homeland of the Dominican Republic to help the economy and provide employment for locals, many of whom are single moms.

Hope Through Work

Growing up in the Dominican Republic, Dan Dalet ’03 and his two brothers lived a comfortable life. They attended good schools, their father worked for a bank and later the auto company Fiat, and their mother was a portrait photographer. As a surfer, Dalet took full advantage of the white sand beaches and amazing weather.

But Dalet also knew the DR’s strong GDP and popular tourist resorts didn’t tell the whole story of his country. “If you drive 10 miles in the opposite direction of those beaches, you find yourself in poverty and underdevelopment,” he says. “As a youth, I always had the idea that someday I would come back to my country and add value.”

First, he traveled to Babson to earn his undergraduate degree. Intrigued by the world of finance, he worked for a private bank in Florida after finishing his studies, and then he helped establish a Boston-based hedge fund comprising entrepreneurial companies. But around the time of the economic collapse in 2008, Dalet began rethinking the long hours and stress of his job, and he couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that his work wasn’t making a lasting impact on the economy or people’s lives.

Dalet began to wonder if it was time to head home. He imagined doing his part for the local economy by launching a company, and he was casting around for ideas when a conversation with his parents grabbed his attention. They were talking about the health benefits of coconut oil. Initially, Dalet was skeptical, but then his uncle, a physician, chimed in, saying that he thought new research about coconut oil was compelling. It was the proverbial lightbulb moment. “I thought, we’re surrounded by coconuts here,” Dalet says. “Why aren’t we making very high-quality, organic coconut oil?”

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Dan Dalet (left) at SoloCoco

Historically, the Dominican Republic has harvested coconuts and exported them as produce or raw material. But Dalet imagined something new: processing the coconuts and turning them into high-quality products before export. So in 2011 he and his wife moved to the DR, and Dalet dove in, experimenting with the production process at a manufacturing facility he established in a rural area 3 1/2 hours from the capital. A year into the venture, however, Dalet hit a significant roadblock. When trying to recruit workers, he discovered that few were available, because most had left the rural area to find work in the city.

Undaunted, Dalet started over. This time he partnered with his cousin Abel Gonzalez, opening a new plant in San Pedro de Macoris, a city with a population of about 195,000 in the southeast region of the island. As they prepared once again to bring on staff, they advertised a willingness to hire applicants who lacked typical experience but demonstrated promise and a desire to work.

One morning in November 2014, they drove to their plant to interview potential employees. What they encountered stunned them. “There was a line of more than 250 women waiting outside,” Dalet remembers. Most were single mothers in their mid-20s, raising three to five children on their own. Many never had attended high school. One woman told Dalet that she was willing to do anything to feed her children, but no one would hire her.

“The sense of despair and hopelessness impacted us profoundly,” Dalet recalls. Although he always had been aware of income disparity in the DR, Dalet still was startled by the severity of the poverty and the lack of options for these women and their children. He and his cousin saw their upbringing and access to education with new eyes. “That day changed us as human beings,” he says, “and changed us as entrepreneurs.”

Running a successful company would no longer be enough. Dalet and Gonzalez made a strategic decision to launch as a socially conscious venture designed around the well-being of its workers. They called their company SoloCoco, which translates to “just coconut” in English. (“Just” is intended as a double-entendre, meaning both “simply” and “fair,” Dalet says.) They hired more women than they initially planned and created a flexible work schedule that would allow employees to work as little as one or two days a week.

Dalet has seen statistics suggesting that a high percentage of children in the Dominican Republic are born to single mothers. These children are more likely to experience poverty and drop out of school, he notes. Many don’t attend school because they lack basic resources, such as school supplies. Those who do attend often experience frequent illnesses and absences because of a lack of sanitation and basic health care. These factors put high school graduation out of reach for many children of single mothers, Dalet explains.

Faced with these daunting statistics, Dalet worked to earn certification by the Fair Trade Sustainability Alliance, a New York-based organization that oversees the well-being of a company’s workers. In addition to offering his workers health care, Dalet partnered with FairTSA to set up a co-pay fund to help with costs not covered by insurance and a fund to cover the cost of school supplies for employees’ children. Another initiative, driven by SoloCoco staff, focuses on employee housing and sanitation. Last summer, the company built its first concrete house, complete with indoor plumbing, for one of SoloCoco’s single-mom employees.

The business is growing. SoloCoco now sells its coconut oil and body-care products in more than 10 countries, and they are carried by 75 Whole Foods stores in the Northeast U.S. This growth comes with challenges, however. “Our biggest problems right now are cash flow and capital requirements,” Dalet says. “It’s harder to find startup funds in the DR, and we can’t borrow money because interest rates are high and lending for small businesses is rare. We’re all self-funded at this time.” Others in Dalet’s family contribute to the business. His wife is a certified natural skin-care formulator, and she develops the company’s organic, personal-care product line. When Dalet’s father retired from Fiat two years ago, he began working for the company in an administrative role.

Dalet says he is motivated daily by what SoloCoco means for his employees. “The most important reward has been seeing the transformation of these families and these kids,” he says.

He and his cousin hope their success motivates more entrepreneurs to come home. “If we do a good enough job with this, it’ll inspire more people to come back and build on our trails,” Dalet says. “This country doesn’t need one SoloCoco. It needs 1,000 of them.”

An Agent of Change

Alex Souza ’09 was born in Mexico City. Although his family moved to San Diego when he was 2, they returned to Mexico City in time for him to start high school. Part of the motivation around the moves was an opportunity to experience other cultures. “Our parents really wanted us to go out there and see the world,” Souza says. “If there was money to spend, we spent it on travel.”

Photo: Alicia Vera

Alex Souza ’09 founded Pixza in Mexico City to help homeless youths change their lives.

His mother, Alejandra, also instilled in Souza and his sisters the importance of helping those in need, bringing them to volunteer with Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity in Mexico City. A life coach, Alejandra taught her children that the best way to help people is by offering them tools to reshape their lives. “That’s always been a big thing in my family, to recognize that you are an agent of change,” he says. “If you want to change the world, you cannot sit around and wait for things to happen.”

When the time came for college, Souza chose Babson for its focus on entrepreneurship and the chance to live in a new place. His college years included a semester at sea and opportunities to study abroad at the London School of Economics, as well as in Uganda and Hong Kong. After college, he returned to Africa with fellow Babson alumni to start an English-language school and management-training program in Rwanda. The program included an initiative that helped underprivileged students; for every 12 students who paid full tuition to the program, one student attended tuition-free.

After successfully launching the business in Rwanda, Souza wanted to build his knowledge of social and economic development. So he sold his stake and enrolled at Columbia University for a master’s in public administration and development practice. While in school, he spent a semester in Bhutan and introduced a program that measures national well-being. After graduation, he moved to Rio de Janeiro to work with the Inter-American Development Bank, which aims to reduce poverty and inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean through financial and technical support; Souza helped establish sports programs for youths living in Rio slums.

When his contract with the IDB ended, Souza turned his attention to home. “I had already helped solve issues outside my own country and learned so much,” Souza says. “But after working in Rwanda and Uganda, Brazil and Bhutan, I decided to go back to Mexico to see what I could do here.”

Photo: Alicia Vera

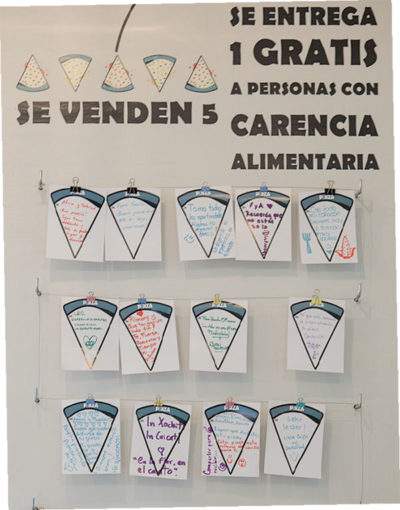

Sign inside Pixza

Souza felt drawn to the plight of Mexico City’s homeless teens and young adults, many of whom are born into homelessness. Hoping to intervene before these youths became adults, Souza began to think about ways to use his Babson-earned entrepreneurial skills. While at grad school in New York City, he had craved a Mexican food known as huarache, which is made with blue corn, and he theorized that the ingredient might make a tasty pizza crust. The idea resurfaced when he decided that a restaurant would make an ideal work experience for homeless youths. Souza spent four intense months developing a blue corn pizza crust that could be topped with traditional Mexican ingredients, including grasshoppers and zucchini blossoms. He called his restaurant Pixza (based on a common Mexican pronunciation of “pizza”), and envisioned “a social empowerment platform disguised as a pizzeria.”

For every five slices sold at the restaurant, the Pixza team donates a sixth slice to youths at a nearby homeless shelter. They deliver all the slices on Sundays. But Souza aims to do more than feed the teens. “It starts with a slice, because that’s a good reason to come together and talk,” he says. “But we want to move on to something bigger.”

Based on his previous experiences with social empowerment programs, Souza developed a detailed, multistage intervention that he calls “The Route of Change.” When youths at the shelter receive their first piece of pizza, they also receive a bracelet, which is punched each time they accept a slice. After the fifth slice, they must complete a small volunteer project of their choice, such as delivering a slice of pizza to a friend. “Instead of just being willing to receive, they have to be willing to give as well,” Souza says.

Kids who don’t complete this step are out of the program. Those who finish receive five more slices and a chance to complete a larger volunteer project. If they hit that milestone, they advance to receiving a shower, haircut, doctor’s appointment, T-shirt, and daylong life-skills course. When they complete those steps, they receive a formal job offer at Pixza, a regular salary, and a job title: Agent of Change. They get restaurant skills training and their own life coach. “The coach helps them develop a personal and professional plan,” Souza says. “Since they’ve been living on the streets, many don’t have the ability to dream.”

Professional life coaches, including Souza’s mother, usually donate time to work with the teens. In the final stages of the program, Souza and his team help participants find housing. Since Pixza launched in 2015, it has graduated and employed 23 kids, including four who have moved into housing. The entire program is funded by restaurant revenues.

Souza has opened a second location but has learned that restaurant management isn’t his strong suit, so he currently is seeking a business partner with this expertise. “I want a partner who actually loves to run restaurants, so we can open up many more locations, and I can focus on the part I’m better at, which is the social empowerment aspect,” Souza says. One day, he hopes to open an institute where he can train homeless youths for a range of roles in the food and beverage industry.

Pixza’s success has taught him the power of business to address social problems. “You can make that an objective from day one,” he says. “It’s amazing how you can use a for-profit business to make a difference.”

Photo: Greta Rybus

Jessica Wright ’11 lived in Ireland for two years, but she knew she would return to North Conway, New Hampshire, some day. Now she’s a local food systems advocate and part of a group that encourages young adults to settle in the area.

Building Communities

Jessica Wright ’11 adored her childhood in North Conway, which is in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. She was 10 when her family moved to this village, popular with tourists, skiers, and hikers. Her mother and stepfather opened the Metropolitan Coffee House in a historic building that once held North Conway’s bank. Wright and her sister spent much of their teen years working at the family business. “It evolved into this really cool community space where people would come and go for open mic night,” Wright says. “Our friends would come for teen night. Given the small town, and the central location, we knew everyone in town.”

While at Babson, however, Wright became interested in travel. She spent a semester in Ireland at University College Cork and fell in love with the place. After graduation, Wright interned with the Family Equality Council in Boston and considered law school, but she decided instead to return to County Cork in Ireland. She spent two years working as a nanny, traveling, playing rugby, and volunteering on organic farms. Those volunteer stints fueled Wright’s passion for farming and locally grown food.

As Wright prepared to leave Ireland, she applied to law school, but life as a lawyer still didn’t feel quite right. Then she found a master’s program at Vermont Law School focused on environmental law and policy. It would prepare her for a career in advocacy, and, apart from occasional on-campus courses in Vermont, she could do most of the work online, clearing the way for her to return to North Conway. “Coming back from Ireland, I just knew that I wanted to be here,” she says. “I love being in the mountains and an hour from the ocean. I love the snow and skiing. There’s nothing like hiking in the White Mountain National Forest in the fall, when the trees look like they’re on fire because the colors are so phenomenal. And I think my favorite part is that the Saco River runs right through the heart of where we live.” Wright takes frequent hikes along the water and ends hot summer runs with a dip in the river.

As she wrapped up her master’s degree, Wright began volunteering for the Upper Saco Valley Land Trust, a North Conway-based organization that aims to protect land from development. The work seemed like a good way to use her environmental law expertise to give back to the village; Wright served on the development committee and then took a part-time administrative position. When the land trust received several grants to support regional food-system projects, the leadership team used the funds to offer Wright a full-time position as a local food systems advocate, which she enthusiastically accepted.

“I work with family-scale farms to make sure that farming is a viable enterprise here,” Wright says. She leads collective efforts to help farmers market their products, creating and maintaining directories that allow customers to find local food, and working to promote area farmers markets. Wright feels lucky to spend her days visiting local farms, checking out greenhouses, fields, and farm animals. “That’s what I’m working for, to make sure that these people can keep doing what they’re so passionate about,” she says.

Photo: Greta Rybus

Jessica Wright works for the Upper Saco Valley Land Trust.

But Wright’s choice to live in North Conway also involves some sacrifice. Because it’s a tourist area, housing can be expensive. At the same time, salaries typically lag behind those in cities, so Wright holds a second job as a bartender to help pay her student loans and mortgage. Also, few other permanent residents are in their 20s or early 30s. “People who might want to put down roots are delaying that until they’re 35 or 40,” Wright says. “They work on their careers in Boston or Portland or Portsmouth and wait until they have a better handle on their finances to come back and raise their families.”

Hoping to find solutions, Wright is chair of a group known as STAY MWV, for Supporting the Active Young Professionals of the Mount Washington Valley. In 2016, the group established a student debt scholarship that helps pay recipients’ loans for up to a year. “We’ve had so many discussions about the apparent lack of young people and examined the barriers to living up here,” she says. “If we could alleviate student debt for someone for one year, think how much more engaged they could be in their community. They could leave that second job and coach soccer or save for a house.”

Wright plans to continue her efforts to convince young adults to commit to North Conway. “The best thing about the work I do is knowing I’m benefiting the community that helped raise me, that’s helping raise a whole new generation of children, and where I’ll hopefully raise my own children one day,” she says. “That’s so rewarding.”