Stuart Harper ’74 in Buffalo, New York, at the Buffalo City Mission, where he is executive director

On the first day of his second career, Stuart Harper ’74 stood before a class full of men in the early, fragile days of sobriety. On the blackboard, he wrote the word “forgiveness.”

Until this moment, Harper had been a salesman. He was good at sales, a natural, and selling whatever needed to be sold had provided him with a comfortable life. But in recent years, that work no longer felt like enough. “As we get older, we look through our lives and we think, what have we done that is important?” he says. Seeking an answer ultimately led him to become executive director of the Buffalo City Mission, a homeless shelter and social services organization in Buffalo, New York, that provides meals, a bed, and guidance to thousands in need every year.

On his first day at the institution, though, the then 56-year-old Harper felt uncertain. “I have no idea what I’m doing here,” he thought, and then he was called upon to speak before that class full of men. Harper had been tasked with filling in for their absent instructor.

Standing before them, Harper felt his uncertainty fade away. In his pocket, he carried an Alcoholics Anonymous coin marking his own years in recovery, so he knew the pain and fear, the guilt and the helplessness, that the men felt. Opening up to them, Harper told the men of his darker days, and he told them about the importance of forgiveness. “You need to forgive yourself and move on,” he said.

In that room, Harper realized his search for more fulfilling work had ended. The second act of his career, and of his life, had begun. “This is exactly where I should be,” Harper thought to himself. “I felt like I was home for the first time in my life.”

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Romance writer Kevin Symmons, MBA’81, in his home office in Plymouth, Massachusetts

I Didn’t Intend to Do That

Something different. A departure. Second careers offer an opportunity to dream up a new story for a life.

For Kevin Symmons, MBA’81, the story of his life had been plumbing. After graduating from college, he started at his uncle’s company, Symmons Industries, which manufactures plumbing fittings such as valves, faucets, and shower heads. Symmons never intended to stay long, but that’s exactly what happened. Thirty-plus years flew by. Symmons became president and COO. Business was good.

By the time he reached his 50s, however, Symmons was done. He was done with meetings, and he was done with the day-to-day grind. “It wasn’t fun anymore,” he says. So in 2001 he retired at 55. A lover of the outdoors, he planned for a relaxing yet conventional retirement of boating and golfing. A mere nine days later, though, life took a turn while Symmons was moving a 50-pound sandbag into his car. “I collapsed in the parking lot,” he says. “I thought someone had shot me.” Turns out he had fractured a disk in his back and would face months of recovery.

The injury may have sidelined Symmons, but it also opened up an unexpected career opportunity. Through the years, he had flirted with the idea of writing and often joked about cranking out the great American novel. Now that he was laid up with nowhere to go, his wife said, “Why not give it a shot?” And so he did. He found the work hard but enthralling. “Once I started doing it, I was hooked,” he says. “I loved the craft. I loved creating. I loved building these worlds and telling stories.”

That he enjoyed writing wasn’t too much of a surprise to Symmons. But the subject of the tales that landed on his computer screen was unexpected: romance. Sure, he admits to a softer side (“I’m not averse to watching a Hallmark movie”). But to go from selling plumbing supplies to writing about love? “It does raise a few eyebrows,” he says. “When I started writing, that’s what came out. I actually didn’t intend to do that.”

At first, his romance novels didn’t set many hearts aflame. Attending a writers conference, he showed his work to others. “They said it wasn’t ready for prime time,” he says. “I thought people would be knocking on the door to publish me. I was so naive.” Still, Symmons kept at it and stayed patient. Years passed. “Maybe you were successful in your first career,” he says, “but you can’t expect your second career to be as successful right off the bat.”

Book publishing, in particular, is a difficult industry to break into. Symmons once talked to an agent who revealed that he received a thousand submissions a month and maybe acknowledged two of them. “You have so much rejection in this business,” Symmons says. “It’s not easy.” Finally in 2012, more than a decade after his back injury, Symmons found a small, award-winning publisher that wanted to put out his novel, Rite of Passage. “I was blown away,” he says. “It’s kind of like being drafted in baseball. All of a sudden someone is now paying you to do something you love.”

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Three more published novels have followed as Symmons has found success in a genre not accustomed to his gender. (Attending a romance writers conference one time, he discovered that he was one of only a few men.) Symmons points out, however, that his books aren’t strictly romance novels. “Romantic thriller” is the term he prefers. The novels contain their fair share of romance, but love blossoms in worlds that are tough and mysterious. Rite of Passage, for instance, involves the paranormal, and the author spent time with a Wiccan high priestess on Cape Cod while writing it. Another, Out of the Storm, concerns an enigmatic woman and domestic terrorists. “It’s American Sniper meets Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” Symmons says.

He conjures up these stories at his home, which sits near a golf course in Plymouth, Massachusetts. When he’s writing at night, he’ll close the French doors that lead to his office and listen to music through headphones. The work is solitary, but Symmons gives a lot of readings, so he meets people who share how his stories have affected them. “They’ve had a terrible day at the office,” he says, “they come home, they pick up your book, and they say, oh God, this is taking me to a place where I really want to go.” Symmons never received that kind of reaction when he was selling faucets. “I sold plumbing for over 30 years,” he says. “Maybe it improves people’s lives—you can’t live without plumbing. But it doesn’t have the same rush as having a reader say they didn’t want your book to end. That’s legit.”

Your Position in the Universe

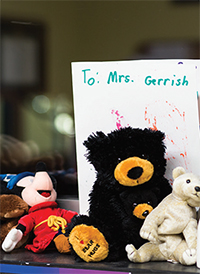

For those feeling skittish about launching a second career, Terry Gerrish ’79 has one piece of advice: Go for it. “Life is so short,” she says. “Do what you want to do. What do you have to lose? Go toward the thing that gives you joy.”

Gerrish receives joy from teaching and working with children. She is the principal of Loella F. Dewing Elementary School in Tewksbury, Massachusetts. At Dewing, 474 students in preschool through second grade are taught not only reading, writing, and arithmetic, but also the basics of what going to school is all about. They learn to raise their hand to be called on, to hold a pencil, to tie their shoes, to get along with each other. “We are forming the foundation on which all learning can happen,” Gerrish says. At the start of every day, she handles the morning announcements, keeping them short but sweet. The national anthem is played, and Gerrish reads the day’s birthdays and, without fail, the lunch menu. “The most important thing you can tell kids is what’s for lunch,” she says. “Kids don’t think, ‘What am I doing in math today?’ They wonder about lunch.”

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Principal Terry Gerrish at the Loella F. Dewing Elementary School in Tewksbury, Massachusetts

As principal, Gerrish must devote her energy to any number of matters—teachers, parents, facilities, IT, curriculum, supplies. Her day is so full that she often doesn’t have time to finish her morning tea until the late afternoon. “It’s crazy busy, but it’s the best job in the world,” she says.

As much as she enjoys education, Gerrish began her career far from the classroom, working a series of jobs in accounting and business management. Her life was numbers, how they added up to profits and losses, and she sometimes witnessed how cold and cruel the bottom line can be. In the late 1980s, she became chief operating officer of her father-in-law’s lumberyard, which had fallen on hard times. “The first thing I had to do was lay off 25 percent of the workforce,” she says. “It was either that or the company would shut down.” Her father-in-law, whom she calls the “most honest, hard-working man I ever met,” was retiring and couldn’t bring himself to let go employees, many of whom had worked for him for years. Gerrish tried to do right by him, the workers, and the company. “We made sure everyone who left had a job,” she says. “We paid off every dollar of debt the company owed.”

From there, Gerrish worked for a property management company as an interim operating officer, a job that involved evicting people whose rent was overdue. She worried about the evictees, about whether they had lost their jobs or were fighting addictions or simply didn’t know how to manage their money. “I had to throw people out of their homes, whether it was justified or not,” she says. “I found myself feeling more sympathy for the tenant than the property owner.” Once the tenants were gone, Gerrish made sure the locks were changed and the units were clean, so as to be rented out again.

These trying experiences came during a time when Gerrish was attending Sunday services regularly. She had fallen away from her faith, but a church a friend had recommended made her feel welcomed and inspired. She sang in the choir, taught Sunday school, and began questioning her life’s direction. “You start to think about your position in the universe,” she says. “I wanted to make the world better. It sounds hokey. But the way to make it better is to provide hope and skills for the next generation.”

Photo: Pat Piasecki

So Gerrish ended up in graduate school earning a master’s degree in education. Taking classes felt uneasy at first, given how unfamiliar she was with the subject matter. “It was a whole different language,” she says. “That first class I was scared witless.” But course after course, she fell in love with education, and after earning her degree, she landed her first teaching job at Sterling Middle School in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was 40. The principal called her his “rookie of the year.”

Gerrish looks back fondly on her early years in the classroom. “I had come home,” she says. “When I got in the moment, there was nothing but me and the kids. I loved being a teacher.” Many of the students at Sterling, however, lived tough lives. At the time, says Gerrish, 93 percent of them received free or reduced-price lunches. She and the other teachers did their best to look after their classes. “Those children came to school, and they were loved, and they learned, and they were safe,” she says. She remembers one student who brought his mom to class after report cards were distributed. “She didn’t believe the report card was his,” Gerrish says. “It was the first A he had ever gotten.” Another student was homeless and living in a shelter, and he always brought a green trash bag to school full of his possessions. But he was determined, and he came an hour early every day to catch up because he had missed so much school previously. He graduated near the top of his class.

Over time, Gerrish moved from the classroom into school administration, serving in various roles, including as principal of a Chelsea elementary school for six years. She learned to do whatever is needed for her schools, whether becoming a master in grant writing or keeping her promise to dye her hair blue after students reached a reading goal. “It took me three weeks and two dye jobs to have my normal hair again,” she says.

This is her first year at Dewing. Out her office windows, she can see a physical education class running and playing, and she can watch as students board buses for home at the end of the day. An American flag waves in the breeze. “There will be times when I go home singing,” she says. “I like to sing.”

I Lost All My Toys

A second career opens a new chapter in a life, but the past remains. Stuart Harper knows this firsthand. He may never have run a homeless facility before, but his past experiences, both professionally and personally, made him an ideal candidate to lead the Buffalo City Mission. Just in terms of operations, his years of experience in business and sales were badly needed. Managed by well-intentioned people who didn’t have a lot of financial know-how, Buffalo City was a bloated institution reliant on donations from overburdened local churches. “We were broke,” Harper says. “I was bleeding half a million dollars a quarter.”

As important to leading the organization, though, were his personal experiences with drug and alcohol addiction. He identifies with Buffalo City’s clients. “I lost everything,” he says. “They lost everything.” Although he had led a successful life on the surface—big house, wife, and three kids—Harper says in reality he was a functioning addict. Then his life unraveled in the late 1980s after he had used money from early business successes to open his own enterprise: a sporting goods store specializing in hockey equipment. “It was something I always wanted to do,” he says. “It was good at first.” But with free time during the offseason, his demons eventually got the better of him. He lost the store, found himself in hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt, and landed in rehab, where his wife told him she wanted a divorce. “She had every right to do that,” he says. “I totally understand why she needed to do that.”

Arriving in rehab, Harper tried to find a way out of the mess he had created. But slowly, painfully, he accepted the truth: He had hit bottom. “It was a humbling time,” he says. “I wasn’t going to sweet talk my way out of it.” He prayed. He asked God for help. As if in answer to a prayer, a former inmate named Charlie, who was also in rehab, stayed by Harper’s side and gave him support. Weeks later, Charlie would be murdered by his old gang, but Harper never forgot him. “Whenever I wanted to do cocaine or drink, I pulled out this picture of my three kids, and I’d think of Charlie, and I would go on,” Harper says.

After rehab, Harper rebuilt his life. He repaired his relationship with his children, attended an AA meeting every day, and took a job as a salesperson at a ski shop. He fell into a routine and stayed sober. “I was going to work and coming home, and going to work and coming home,” he says. Time passed. More lucrative jobs followed, including a stint at McGraw-Hill as vice president of sales, which took him all over the world. He also fell in love and remarried; he and his second wife now have two children. Harper was already on the board of Buffalo City when he applied to be its executive director. He knew the job would mean a significant cut in pay, but after having once squandered everything of value in his life, money no longer seemed as important. “I used to believe that whoever dies with the most toys wins,” he says. “I lost all my toys.”

Photo: Matt Wittmeyer

Under Harper’s leadership, the once struggling organization has flourished. He streamlined its operations, eliminating some positions and closing down peripheral departments, such as an unprofitable used-car lot selling donated vehicles. He also formed dozens of partnerships with local agencies, which provide Buffalo City with services from literacy instruction to childhood case management to doctor visits. And he expanded fundraising. Eight years ago when Harper came on board, 15,000 people gave annually to the shelter. Today, that number is 40,000.

When he walks through the facility, Harper can see all the positive offerings provided by the organization, the beds and meals, the after-school program and parenting classes, the substance abuse services and career development initiatives. “We make a real difference in people’s lives,” he says. “I wish I had been doing this work all my life.”

Looking back on his life, on the ups and downs that ultimately led him to a second career helping others, Harper feels relief and gratitude. “I don’t often tell my whole story,” he says. “When I do, I always feel blessed to have come out the other side.”