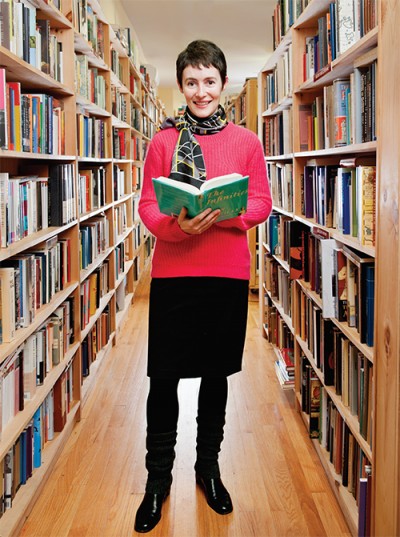

Photo: Webb Chappell

A favorite haunt of Mary O’Donoghue’s is Raven Used Books, located on Boston’s Newbury Street.

For several months, Mary O’Donoghue had worked on the novella, the words growing day by day.

Then, something happened. In a moment of clumsiness, she accidentally deleted the document from the computer. Just like that, 10,000 hard-earned words were gone.

O’Donoghue’s reaction, though, wasn’t what you would expect. She didn’t panic. She wasn’t angry or sad. “It was great,” says the associate professor of English. “It was one of the best things that ever happened.” Instead of a disaster, the loss was more like a cleansing. Truth be told, the novella wasn’t working. Now O’Donoghue was done with it once and for all, save for one worthwhile sentence that she managed to remember. “That was the only thing in there that was true,” she says.

A poet, novelist, and shortstory writer, O’Donoghue knows all too well how chaotic and messy the act of creation can be. For her, the frustrations and triumphs of writing are about the sharing of human experiences. She is, above all, a storyteller. “What if? That is the big question in fiction,” she says. “What if this happened?”

At Babson, O’Donoghue teaches rhetoric, literary translation, Irish literature, and fiction writing. She started at the College as an adjunct faculty member in 2002, shortly after emigrating from her native Ireland, a place that still has a hold on her heart and her writing. She grew up in County Clare on a small farm in the countryside. As someone who builds with words, O’Donoghue is, in a way, following in the footsteps of the many builders and carpenters in her family. “I come from a family who makes things,” she says. The family house was built by her great-grandfather, and she lived there with her three younger sisters. “We ran around and had our fun,” she says. “It was very lovely.” She went to school a few miles down the road in a small village with little more than a church and post office.

O’Donoghue earned her undergraduate and graduate degrees from the National University of Ireland in Galway, but she was curious about America. While she previously had visited the U.S., she moved there permanently in 2001 and saw her career flourish. She has published two books of poetry and a novel, and her work has appeared in various literary magazines. She became a full-time faculty member in 2004.

O’Donoghue still returns to Ireland about twice a year. While visiting, she enjoys watching Ros na Run, an Irish-language soap opera, and she takes walks along the rocky landscape from her family home to a nearby lake. She admits that these visits can be bittersweet. To express how she feels, she turns to the lines of a Philip Larkin poem: “Home is so sad. It stays as it was left,/Shaped to the comfort of the last to go/As if to win them back.”

In America, she thinks often of her old home. Her Hollister office is sprinkled with reminders of the Emerald Isle—a poster for a Galway bookshop, a map of Dublin as seen in the works of James Joyce. Through her writing, she tries to connect with Ireland, to make her work somehow reminiscent of that distant place. This yearning is a big reason O’Donoghue enjoys translating Irish-language poems. “There is that longing to be in the Irish language, to inhabit it,” she says. “I don’t have many opportunities to speak it.” When translating, she obsesses about each word that she uses, making sure the translation’s meaning is clear and true to the original. “I feel an oath of allegiance to get the poems right,” she says.

Home for O’Donoghue in the U.S. is actually two places: Tuscaloosa, Ala., where her professor husband and stepdaughter live; and Boston, where she likes to write at the Boston Athenaeum library, shop at Raven Used Books on Newbury Street, and see the tulips in the Public Garden. To commute to Babson, she takes the train to the Wellesley Hills station and then walks to campus. The 20-minute walk can be quite cold on winter mornings, but she uses the quiet time to think about her classes and her work. “It’s 20 minutes of no surround sound,” she says. “I love that walk.”

On a recent Wednesday morning after enjoying that walk to campus, O’Donoghue is in Malloy 204 going over an assignment with her fiction-writing class. The students have written stories inspired by real-life news headlines, and now they’re taking a small act of courage by sharing in public what they wrote in private.

The stories are handed out, and the students start reading and evaluating each other’s work. Walking around the room, O’Donoghue sidles up to the young writers, advising them to offer criticism that is constructive. Don’t be mean, she says, but don’t be too polite either. Being critical is OK, even if the story seems polished. “Polish is surface,” she says. “It’s not the gut, the heart.”

In the class, O’Donoghue talks a lot about the “animal,” the name a visiting writer gave to the issues and desires that drive someone to put pen to paper or fingers to keys. The animal can be anything: a relationship, an unrequited love, an old home an ocean away. “It’s the thing that’s bothering the writer,” she says. “It needs to walk around the page. Fiction is a place to exercise that a bit.”

For the students’ work, and for her own, O’Donoghue values honesty. Stories can be sad, blunt, and rough. “Their stories don’t have to be pleasant,” she says. “They don’t have to be nice.” Read a story, and you hope it takes you somewhere. “We leave it feeling we’ve been through something,” she says.