On a winter Wednesday morning at the Bowl-O-Rama Family Fun Center, Debbie Zoffoli stands behind the counter and looks over the lanes. Members of the Merry Mixers, a bowling league for ladies who like to chat and exchange pictures of grandchildren, are settling into their seats. Zoffoli grabs the microphone. “Good morning, bowlers,” she says.

A shift leader at Bowl-O-Rama, Zoffoli checks people in and rents them shoes at $3 a pair; the sizes of the regulars she knows by heart. If a Merry Mixer bowls an exceptional game, she awards her a prize. “Come on down, you have won a free game pass,” she says into the microphone. If a pinsetter jams, Zoffoli winds her way behind the lanes to get the game moving again. When she does, the Merry Mixers applaud.

Zoffoli works for Nick Genimatas, MBA’76, who co-owns the Portsmouth, N.H., bowling alley with his sister. Their father opened it in 1956, and Genimatas started working at Bowl-O-Rama when he was 8 or so, serving hamburgers and dishing out ice cream at the snack bar. “I like being here. It’s an enjoyable place to be,” says Genimatas, surrounded by the rhythms of the bowling alley: the rolling of the balls, the smack of the pins, the beeps of the arcade. He has trouble picturing himself working in a more buttoned-up environment. “Could I have been a corporate guy? I don’t know.”

Business at Bowl-O-Rama fluctuates with the seasons and the weather. On a sunny summer day, Bowl-O-Rama becomes a ghost town where tumbleweeds practically blow across the lanes. Things change in winter. When the air grows cold and harsh and the days of beaches and baseball are out of reach, a place like a bowling alley becomes a respite, an oasis of pizza and beer, spares and strikes, sport and competition. “A snowy day is our busiest day,” Genimatas says. “Parents are scrambling for things to do.” During such times, a welcoming hangout can be essential to staying active, and staying sane.

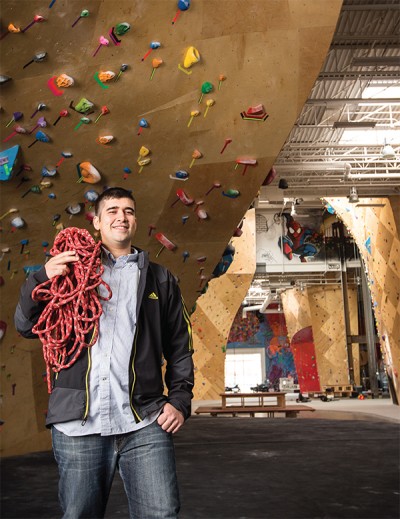

Lance Pinn ’06 in Brooklyn Boulders’ vast climbing

facility in Somerville, Mass.

Venturing High Above

How important is staying active in the winter? When Lance Pinn ’06 came to Babson, he had lived previously in California and Virginia, so winter hit him hard. Hunkering down indoors, he dreaded venturing out. “I had never been to New England,” he says. “I had never experienced cold weather.”

He’s better prepared now. Today, he is co-owner and co-founder of two Brooklyn Boulders rock-climbing facilities: one in Brooklyn, N.Y., the other in Somerville, Mass. If someone were in need of a way to beat the winter blues, a rock-climbing facility makes for a good spot. On a Tuesday morning, Pinn stands in the Somerville location, which is long and large, 40,000 square feet, full of walls to climb and challenges to take on. Pinn is looking up at his fellow co-owner and co-founder, Jeremy Balboni ’05, who scales the wall like a spider. Near the top, 49 feet above the ground, Balboni climbs upside down on a part of the wall known as the “tongue.” He then dangles from the ceiling from a rope and sinks back to earth. “He’s nasty,” says Pinn, watching his partner.

An avid climber who first turned Pinn on to the sport, Balboni enjoys the physical discipline and problem-solving skills that climbing requires. It also forces him to focus. “You’re truly in the moment,” he says. “You’re living for that one second in front of you.” Pinn remembers his initial foray into climbing with Balboni, how nervous Pinn was at the start and how astonished and excited he felt by the end. “All you think about is getting back on the wall,” he says.

Together the pair revisited a business plan for a climbing facility that Balboni had written while at Babson. After an exhaustive 18-month search to find the right location, they opened their first climbing gym in Brooklyn in 2009 with Stephen Spaeth ’05 (who has since moved on to a career in film production). They soon noticed how much the climbers enjoyed hanging out at the facility. Sitting with their laptops and talking for hours, they turned the gym into a vibrant community, one that sees 60,000 unique visitors annually.

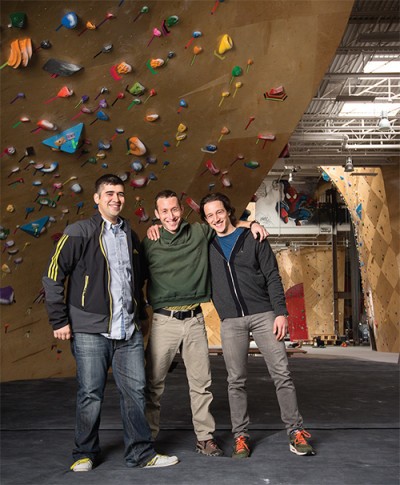

Lance Pinn ’06 (left to right), Jesse Levin ’08, and Jeremy Balboni ’05 are partners in the climbing venture.

Pinn and Balboni wanted to create even more of a community vibe when they, along with four other partners (including Jesse Levin ’08 and Brandon Bell, MBA’12), opened the Somerville Brooklyn Boulders last year. So besides climbing, the facility offers saunas, cardio machines, a weight room, lounge, and collaborative work space. As many as 300 people fill the location during its busiest times, giving the space a hum of activity. “We tried to create an environment where you don’t want to leave,” Pinn says. “We want you here for five or six hours.” During that time, Pinn envisions visitors climbing, meeting people, doing some work, and feeling inspired. Spread throughout the location is art of all types: woodwork, metalwork, graffiti, photography, and motorcycles displayed like museum pieces. Above it all, written near the ceiling, are the words “Exist to Inspire.” “We hope you have an epiphany at our space,” Pinn says.

More Brooklyn Boulders are slated to open in the near future: Queens, N.Y., and Chicago this year, Manhattan in 2015. As they expand, the Brooklyn Boulders team will be thinking of this number: three. That’s the percentage of Americans who go climbing at least once a year. A big obstacle to growth is convincing the other 97 percent to give climbing a try. “Most people don’t think they can do it,” Pinn says. “Most people assume it’s about upper body strength.” In actuality, climbing is much more about using one’s legs, he says. Climbers step first with their legs and then reach with their arms. “If you can climb a ladder, you can climb a rock wall,” Pinn says. “The first step is being able to realize you can do it.”

Joe McManus, MBA’06, CAM’08, of the Pro Squash Tour, which stages tournaments for professional players

Intensity in a Box

Joe McManus, MBA’06, CAM’08, also enjoys an intense indoor activity, but his sport of choice is more earthbound, and a lot more claustrophobic. Inside a 32-by-21-foot box, he hurls a small rubber ball at the wall while trying to outsmart and outmaneuver his opponent, who often seems right on top of him in the small space.

This is the sport of squash, and it’s full of sweat, speed, and strategy. “Some people have called it chess at 150 mph,” he says. With squash, McManus not only has found a rigorous workout, one that can burn up to 1,000 calories in an hour, but also a business and profession. He is head squash coach at Tufts University and commissioner, CEO, and founder of the Framingham, Mass.-based Pro Squash Tour, which stages tournaments for professional players in the U.S. and abroad. With the tour, McManus is shaking up a growing sport that for years seemed relegated to country clubs and preparatory schools. In some staid squash circles, he’s even considered controversial. “If you’re into squash,” he says, “what I do is a bit unusual.”

McManus first played squash as a young man, but the sport took awhile to turn into a career. His life has seen various twists and turns. “I always wanted to be the kid who at 15 knew who he wanted to be,” he says. “I wasn’t.” He majored in classical music performance, worked as a teacher, did political consulting, served as executive director of the American Diabetes Association, and worked in China as a business consultant.

Through the years, though, he hankered to start a business, and he came to Babson to learn how to do just that. In squash, he saw a great opportunity. Twenty million people play the game worldwide, and squash players in the U.S. tend to be highly educated and affluent. “If you add up all the squash fans in America, it’s a great demographic to market to,” McManus says.

He started his tour in 2009. From the beginning, he wanted to try new ideas and be entertaining. “Squash is a great sport, but it’s very dry,” he says. McManus tweaked the rules, and he added touches that wouldn’t be out of place during an NBA game: music, player interviews before and after matches, and a remote-controlled indoor blimp hovering over the audience. He launched Squash Ezine, a weekly newsletter that includes Truth and Rumors, a popular column giving a gossipy rundown of squash happenings.

Joe McManus’ squash tour has made some tweaks to the game. “If you’re into squash, what I do is a bit unusual,” he says.

During the tour’s first tournament, he had women in provocative outfits stroll out holding signs announcing each game. McManus admits he went too far with this bit of envelope pushing. A sight common in boxing matches didn’t work in the intimate confines of a squash court. “It was the wrong thing to do,” he says. “It was a nightmare.” The women never made another appearance, but they left an impact. Five years later, McManus is still asked about the stunt.

To play on a professional squash tour is not the same as playing professional tennis or golf. Players aren’t getting rich, McManus says. Still the tour has seen success. It has three circuits: Canada; Asia-Pacific, with stops in countries such as Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines; and America, which has about 20 stops in the U.S. Up to 30,000 people have watched live streams of matches on the tour’s Pro Squash TV site.

The antics and ambition of the new tour have resulted in a squabble with squash’s establishment. The Professional Squash Association, which is based in England and organizes elite tournaments around the world, has banned its players from participating in the upstart Pro Squash Tour.

Initially, McManus looked at legal options to lift the ban, but decided against pursuing them. He believes the squash association, which has been around for decades, is trying to strangle competition. “America is a growth market,” he says. “They’re aware of that.”

McManus actually thinks the friction with the association can be good for his tour and the sport. He doesn’t mind stirring things up a little. “If you’re not, you’re not doing anything of interest,” McManus says.

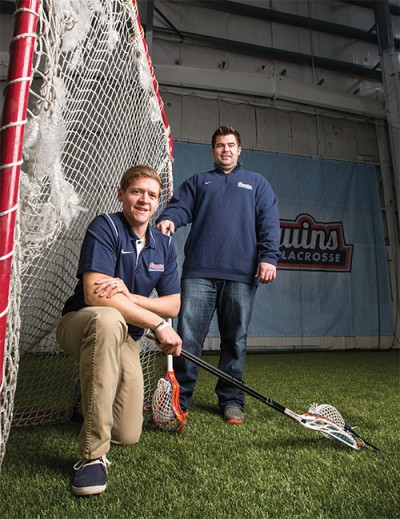

Jason Wellemeyer ’08 (left) and Tyler Low ’09 of PrimeTime Lacrosse

A Summer Sport in Winter

On first blush, lacrosse wouldn’t seem to be a good wintertime activity. Squash. Climbing. Bowling. These make sense. But think of lacrosse, and you picture green fields, open skies, and athletes running in the breeze.

For sure, PrimeTime Lacrosse, co-owned and co-founded by Tyler Low ’09 and Jason Wellemeyer ’08, offers plenty of lacrosse activities when the weather is warm. In the summer, PrimeTime runs 30 to 40 day camps throughout New England, the mid-Atlantic, and Texas. It also organizes 30 select teams for elementary through high school students, and as many as 3,000 players will enroll in their camps and clinics throughout the year.

PrimeTime doesn’t close, though, when the temperatures plummet. The game continues inside its Natick, Mass., facility. Located across from a dog-fence company in an industrial area, the facility can be easy to miss. PrimeTime’s building is non- descript, the sides covered in corrugated metal, but in a window a picture of a penguin with a lacrosse stick lets visitors know they’re in the right spot.

Immediately inside are offices and a place for players and families to hang out. Children watch TV and do homework, and a golden retriever named Charlie lounges in Wellemeyer’s office. Wellemeyer himself may be about to jet off to a PrimeTime event in another state, or he may fill you in on his latest exploits and misadventures on the lacrosse field. Both he and Low played lacrosse at Babson, and they still play as part of an adult team sponsored by PrimeTime. They’re also lacrosse coaches at the University of Massachusetts Boston. “My thumb is probably broken and my shoulder is a mess,” Wellemeyer says. “It’s part of the game.”

PrimeTime’s Natick, Mass., facility allows lacrosse players to work on fundamentals during winter months.

Walk to the back of the building, and the facility opens into a long and wide space, 100 feet by 55 feet, that used to be a factory. With green turf on the ground and nets at either end, the space allows players to work on the game’s fundamentals—catching, throwing, picking a ball off the ground—when fields are covered in snow. “It’s constantly busy,” Wellemeyer says. “We’re a year-round operation.”

PrimeTime can operate year-round because lacrosse’s popularity has soared in recent years, as the sport has moved beyond the Northeast where it’s traditionally played. Low and Wellemeyer started PrimeTime in 2007 when they were still students at Babson, and they’ve watched as demand for their offerings increases. Having an indoor space became a necessity. “We’ve grown with lacrosse,” Wellemeyer says. “It’s the new sport that’s taking over.” Athletes are drawn to lacrosse’s speed. In comparison, baseball seems slow. “Football and hockey players are looking for another fast-paced game,” Low says.

Low and Wellemeyer hope they influence players beyond lacrosse. Besides the skills and drills, they want to teach “the things that may go by the wayside these days,” Wellemeyer says. They focus on sportsmanship, dedication, teamwork, and respecting others. “It allows us to teach values,” Low says. “It’s less about wins and losses and more about preparing them for other aspects of their lives.”

He may be co-owner of a bowling alley that has been in his family for nearly 60 years, but Nick Genimatas admits that his bowling skills are lacking.

Let the Good Times Roll

At the Bowl-O-Rama Family Fun Center, the balls continue to roll down the lanes and crack into the pins. After a while, the constant racket blends together, becoming almost like white noise.

These are the sounds Nick Genimatas has known his entire life, ever since his father and two partners paid $15,000 each to start Bowl-O-Rama. To buy the 20 pinsetters they needed, the partners put down $25 for each machine. “There’s a lot of nostalgia here,” Genimatas says. “We’re proud of the 57 years under one family.”

Through the years, Genimatas has watched how the business of bowling has changed. In the early days of Bowl-O-Rama, 60 to 70 percent of its business was league play. Stay-at-home moms played in leagues during the day, and employees of local businesses filled the rosters of nighttime leagues. The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard had a couple of leagues. The Portsmouth Herald had one. Today, leagues make up only 15 percent of the bowling alley’s business. More women work nowadays, and people no longer stay at the same company their whole lives, making friends and socializing together. “Bowling, in a way, is reflective of society,” Genimatas says. “Bowling has changed because society has changed.”

That’s not to say business isn’t good at Bowl-O-Rama. It hosts lots of birthday parties and corporate events, and its arcade and cafe, which sells beer and wine, are solid moneymakers. And the bowling alley still grows busy with people looking to spend time with friends. On weekends, the house lights are turned down and the music and disco lights are turned up for “cosmic” bowling. When young children visit, the lanes are fitted with inflatable bump-ers to prevent the youngsters from throwing the ball in the gutter.

Strong leagues still call Bowl-O-Rama home. On Wednesday night, the serious competitors of the Men’s Classic League gather. Last year, the league’s prize fund was $18,000. When they bowl, the music in the bowling alley is turned off, the men needing to concentrate as if they were putting a golf ball. On Tuesday mornings, the Bowling Belles congregate. That group’s oldest member, Evie, is about 90 and walks with a cane, and when Bowl-O-Rama employees see her coming, they carry her bag of bowling balls for her. “The lady has great spirit,” says Genimatas, who points out that Bowl-O-Rama, like many New England bowling alleys, features the Candlepin style of bowling. Candlepin balls are lighter and smaller than typical bowling balls, so they’re easier for seniors and children to use. “If you’re 3, you can roll it between your legs,” he says.

The good times do roll at Bowl-O-Rama, but Genimatas is 61, and he turns wistful when thinking of the future. None of the family’s next generation seems interested in taking over Bowl-O-Rama, and if the center is sold, the new owner may not keep it a bowling alley because land in the area is so valuable. That makes Genimatas think of all the people through the decades who have come to the bowling alley for parties, reunions, and those snowy winter days. “People in the area have been here, one time or another,” he says. “We’ve been an integral part of the community.” So far, though, Genimatas has no plans to hang up his bowling shoes and retire. “Why rush it?” he says. “Bowling is something I could do for a long time.”