In November 2010, Leah Hurley ’02 was working in her office when she received an email from her mom. “I saw the Bangor Daily News article about Matt and Chris,” her mom wrote, “and I hope you’re OK.”

Matt and Chris are Hurley’s cousins. The three are close, having grown up together in Belfast, a small, working-class town on the Maine coast. “We’re more like siblings than cousins,” Hurley says.

Searching out the article, Hurley found upsetting news. Chris had been arrested the night before in New York City. His younger brother, Matt, was arrested that morning in L.A. Charged with conspiracy to distribute cocaine, the brothers were accused of participating in a Maine drug ring. Both faced a potential minimum sentence of five years in prison.

The news rocked Hurley and her family. “It was totally terrifying,” Hurley says. She watched as her cousins were plunged into the vastness of the criminal justice system, an overburdened bureaucracy that was foreign and unsettling to her. “I was almost embarrassed to realize how big it is and how much I didn’t know about it,” the Portland, Maine, resident says. “I had my eyes ripped wide open.”

To make sense of these experiences and perhaps help other families in similar situations, Hurley decided to document what was happening and began filming. As a founder of Maine’s Camden International Film Festival, which has highlighted the work of emerging documentary filmmakers since 2005, Hurley had long wanted to make a documentary. She now found a subject to focus her camera on, the fear and anger, sadness and uncertainty, that she, her cousins, and her family confronted in the arrests’ aftermath. She calls her documentary Criminal: One Family’s Story, and she’s almost done filming footage. “This is something my soul is called to do,” Hurley says. “I have to tell this story.”

These scenes come from Criminal: One Family’s Story, in which Leah Hurley focuses on her family, who hail from Belfast, Maine, and their experiences with the criminal justice system. In the bottom image, one of her two cousins who was arrested on drug charges stands with his grandmother, Roseann.

These scenes come from Criminal: One Family’s Story, in which Leah Hurley focuses on her family, who hail from Belfast, Maine, and their experiences with the criminal justice system. In the bottom image, one of her two cousins who was arrested on drug charges stands with his grandmother, Roseann.

Such filmmaking is far removed from the industry that grinds out the latest blockbuster playing at the multiplex. Hurley’s budget is small, as is the film’s probable audience. But for Hurley and other filmmakers in the Babson community, documentaries aren’t about special effects, superheroes, and Hollywood spectacle. Direct, intimate, and personal, their work delves into real life and the truths to be found there.

A Story to Tell

Mary Mazzio, Babson’s filmmaker in residence, has been making documentaries for 15 years. When filming, she tries to establish a relationship with her subjects to draw out the tales and truths they have to share. “People will divulge more if they trust you,” says Mazzio, the founder and CEO of 50 Eggs Films, a production company dedicated to creating films with a social message. “I think every human has a remarkable story to tell.”

Mazzio’s films often portray dreamers and fighters, people bucking the odds, taking risks, and making things happen. She profiled immigrant pushcart vendors in The Apple Pushers, inner-city students participating in a nationwide business plan competition in Ten9Eight, and female athletes battling for equality under Title IX in A Hero for Daisy.

Her latest movie, Underwater Dreams, follows a team of high school students, sons of undocumented Mexican immigrants, who in 2004 entered an engineering competition, built a rag-tag underwater robot out of parts from The Home Depot, and won by somehow beating MIT. Mazzio remembers the first time she heard about the team. “I was mesmerized,” she says. “It’s an incredible underdog story.” Mazzio knew the story would make a great documentary, so year after year she checked to see if Warner Bros., which initially owned the rights to the story, was moving ahead with a movie. When the studio’s rights finally lapsed, Mazzio started on her own project, which illustrates how the potential of the robot team wasn’t recognized because its members came from poor immigrant families. “We have tremendous talent in this country that is overlooked,” says Mazzio, who argues that if the U.S. is to remain competitive, it must nurture all its homegrown talent, wherever it might be found.

Mazzio’s route to becoming a documentary filmmaker began, interestingly enough, at a Boston law firm. Mazzio was a partner, and in the pro bono work she performed, helping those in poverty deal with housing issues, she was unsure of the difference she was making. She would assist someone who was about to be evicted, and soon enough, another person facing the same problem would need her help. It seemed a never-ending cycle. Was there perhaps a better way to create a broader impact on society? “How do I give back?” she wondered. “Life is short. You want to do something meaningful.”

While still working as a lawyer, Mazzio started attending film school at Boston University. There she made her first film, A Hero for Daisy, and as it garnered increasing media attention, Mazzio took a leave of absence from her job, then extended the leave, and finally quit. She launched 50 Eggs in 2000. While she’s intrigued by the idea of one day directing a feature film, Mazzio cherishes her independence as a documentary filmmaker. “I like to call the shots,” she says.

Filmmaker Robert Radler ’74 at his home in Thousand Oaks, Calif.

Movies for Myself

Robert Radler ’74 knows all too well the compromises and challenges that go into shooting bigger films. Radler now makes documentaries, but earlier in his career he had directed action movies (Showdown, Best of the Best, and its sequel), as well as TV shows (episodes of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, Hercules, Silk Stalkings, and V.I.P.) and music videos (for artists such as Jackson Browne, George Thorogood, and Crosby, Stills & Nash).

Sometimes, the Thousand Oaks, Calif., resident is reminded of his old life. One day while heading to the beach, Radler came upon a feature film shoot. A mass of people moved about, and dozens of trailers sat parked. He watched wistfully. “I kind of miss that,” he thought. Any nostalgia he feels for those days, however, fades when he thinks about the pressure he faced. “Everyone has an opinion,” he says. “The politics of a feature film when there are $60 million at stake are unspeakable.” Needing a break, Radler has focused on more personal efforts during the last decade or so. “I realized I had worked for everyone but myself,” he says. “What I’m doing now is a much purer form of filmmaking.”

Two of his current projects have roots that stretch back to his youth. One of these, Turn It Up!, is about the electric guitar. In high school and college, Radler played guitar in a band called The Late W. Moulton (named for a massive mausoleum in his old hometown of Framingham, Mass.). As the years went by, though, Radler drifted away from the instrument. He didn’t pick it back up until his son started playing. “I got the old Gibson out from under the bed,” Radler says. “I started feeling the passion again for the instrument.”

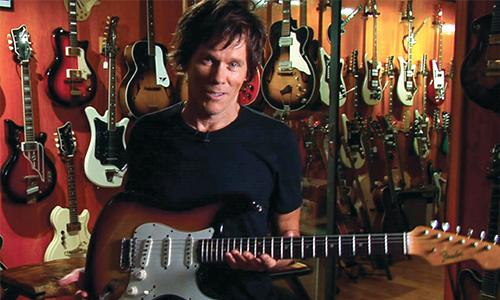

Directed by Robert Radler, Turn It Up! includes a number of guitar players talking about their passion for the instrument. These scenes feature bluesman B.B. King (top) and actor Kevin Bacon (bottom), who narrates the film.

Directed by Robert Radler, Turn It Up! includes a number of guitar players talking about their passion for the instrument. These scenes feature bluesman B.B. King (top) and actor Kevin Bacon (bottom), who narrates the film.

For Turn It Up!, Radler interviewed a host of guitar players, including B.B. King, Slash, the late Les Paul, The Doors’ Robby Krieger, and Kiss’ Paul Stanley. “I wanted to make a movie about mankind’s obsession with the electric guitar,” Radler says. To prepare for the interviews, he researched the guitarists’ individual histories, and he gave many of them a present, a prized amplifier tube from the 1970s, a gift signaling that Radler was one of the tribe, a guitar guy. “They knew I knew my stuff,” he says. “I got into intense conversations.” Radler talked with Paul, in one of the guitar pioneer’s last interviews, for six hours. He talked with King in the bluesman’s tour bus, and the interview lasted so long that King’s band was waiting for him to finish so he could join them onstage.

Another Radler project has been a series of films about the SS United States, a once-mighty ocean liner launched in 1952 that now sits decayed and abandoned on the Philadelphia waterfront. Radler first saw the American-made ship, which still holds the trans-Atlantic speed record, in port at the age of 8. He was smitten. “It looked fast just sitting there,” he says.

So began a lifelong obsession with the SS United States. Radler first did some filming of the ship in 1975. At that point, the ship hadn’t been touched since its last voyage six years earlier, and it still carried remnants of a famous passenger. “Liz Taylor’s cigarettes were in her suite in the ashtray,” Radler says. His initial documentary, SS United States: Lady in Waiting, was released in 2008. Two more films have followed.

For Radler, the ocean liner is a reminder of the boom times of American manufacturing, and he would love to see the ship restored to its former glory. His films have helped raise awareness and money for a conservancy organization desperately trying to find the ship an owner who can give it a new life, perhaps turn it into a water-bound mall or hotel. If an owner can’t be found, the SS United States will probably be sold for scrap metal. “I’m hopeful,” Radler says.

Too Personal?

The subject of Hurley’s documentary also is close to her heart—maybe a bit too close.

When Hurley decided to make a film in the wake of her cousins’ arrests, she initially envisioned a journalistic piece about the business of prisons and the treatment of prisoners. “It wasn’t going to be personal at all,” Hurley says. But then she realized that the film wouldn’t find much of an audience. Prisoners are locked up for a reason, many would say. Why should I watch a movie about them?

True enough, Hurley says, her cousins broke the law, and that warrants punishment. But the criminal justice system is complicated, and Hurley wanted to share up close what going through that system is like. That’s why she decided to turn the lens on her family. Perhaps a more personal approach, showing how a family deals with incarceration, would resonate with audiences, she thought. Hurley began asking family members about participating. Some were open to appearing on camera, some weren’t. The older generation felt the audience might judge the family, and Hurley didn’t try to persuade them otherwise. “I don’t push it,” she says. “I’ve been trying to be respectful.”

As for cousins Matt and Chris, they both said yes to participating but remain uneasy about publicity the film may generate. Both men have finished their time (with plea bargains, Chris was sentenced to 30 months in prison and Matt 56 months), and they worry that the film may make finding and keeping a job more difficult. The film also deals with one cousin’s recovery from heroin addiction, which further complicates matters.

For her part, Hurley admits that she even feels a bit shy talking about her family for this Babson Magazine article (she asked that her cousins’ last name not be used). Of course, Hurley realizes that these privacy issues aren’t going away. The film will eventually be released. But a rough cut of the movie won’t be finished for another year, with the goal of applying to 2016 film festivals, so she thinks her family will grow more comfortable with its personal nature in time. “Hopefully, they will like it and be proud they are a part of it,” she says.

Beyond privacy concerns, Hurley has faced other challenges. As the owner of a marketing firm, Craft Media, she previously had experience organizing shoots for short promotional films, but she was never a director. “I knew the basics,” she says. “I knew enough to maybe get myself in trouble.” To remedy that, Hurley has reached out to colleagues to help with the film’s cinematography and editing. “I have surrounded myself with an amazing team,” she says. “I have really talented friends, and they believe in the film.” Not that she has much money to pay them. Some volunteer their services, some work at a reduced rate, and some offer help in exchange for Hurley’s marketing assistance for their own projects. Otherwise, Hurley becomes a jack-of-all-trades during shoots. “I’m holding the sound boom,” she says. “I’m not going to hire a sound guy.”

Other necessities will demand funds as well: color corrections, music rights, and the making of physical copies of the film, to name a few. Hurley has raised funds from friends and family, and she has applied for grants, which are highly competitive. She also has invested her own money. “It would be nice to recoup my investment, but I don’t look at it that way,” she says. Her goal is simply to make the best film she can. “Matt and Chris are trusting me with their story, and I need to honor that,” she says.

Have Camera, Need Cash

Money issues aren’t unique to Hurley. Many documentary directors want to focus exclusively on making their movies, but that’s an impossibility. “The financials matter,” Mazzio says. “It’s part of the deal.”

Radler took seven years to finish Turn It Up!, but that wasn’t because the filming took that long. At one point, he lost a key investor, and he spent years hustling to obtain permission to use the many songs in the film, a process made more difficult because he didn’t have a big budget. Some artists turned him down, while others took a long time to respond. Just to get Jimi Hendrix’s estate to clear his music for the film took more than two years.

Chris LeSchack, MBA’13, serves as an executive producer of Fight Church (scenes above), a documentary that explores how a number of churches are using mixed martial arts in their ministries to the point where pastors will fight inside a caged ring.

Chris LeSchack, MBA’13, serves as an executive producer of Fight Church (scenes above), a documentary that explores how a number of churches are using mixed martial arts in their ministries to the point where pastors will fight inside a caged ring.

Chris LeSchack, MBA’13, is the executive producer of the documentary Fight Church. The responsibilities of an executive producer can be summed up in one word: money. LeSchack and his team at iMogul, an online site that allows users to read and rate screenplays and then enables producers to peruse that data to find scripts to invest in, agreed to help fund the movie. In exchange, their company’s name and logo were listed prominently on the film’s poster, trailer, and credits. “We thought it would be good for marketing,” says LeSchack, who is iMogul’s CEO and founder. Three other MBA’13 alumni, Paul Proctor, Maxwell Chang, and Ashit Ghevaria, make up the rest of the iMogul team.

Fight Church follows pastors who use mixed martial arts in their ministries. Examining the relationship between violence and religion, the provocative film has received much attention since its spring premiere. The New York Times and Nightline ran stories on it, the Independent Film Festival Boston awarded the film its Grand Jury Prize, and Morgan Spurlock, director of the McDonald’s-skewering Super Size Me, is creating a reality series based on the movie. Distribution deals with Netflix, Lionsgate, and others have recouped LeSchack and iMogul their initial investment, and then some. “That’s not always the case with any film,” he says.

Radler agrees. “It’s difficult to make money with a documentary,” he says. “It is hard as hell to get a documentary in a movie theater, unless you’re a Michael Moore.” That’s not to say his films haven’t found an audience. Lady in Waiting has played extensively on public television, and Turn It Up! will start screening there this fall. He’s also negotiating a distribution deal for Turn It Up!, though Radler laments the declining revenue that comes from DVD sales. The sale of a physical DVD might net a filmmaker $5, but streaming is becoming more and more popular. “With streaming, you might make 10 cents a stream,” he says. “You’ve got to sell a lot of streams.”

In Underwater Dreams, Babson’s filmmaker in residence, Mary Mazzio, chronicles how an underdog science team from a Phoenix high school managed to beat MIT in a 2004 robotics competition. These scenes show the neighborhood near their high school (top) and team members with their teacher 10 years later (bottom).

In Underwater Dreams, Babson’s filmmaker in residence, Mary Mazzio, chronicles how an underdog science team from a Phoenix high school managed to beat MIT in a 2004 robotics competition. These scenes show the neighborhood near their high school (top) and team members with their teacher 10 years later (bottom).

Mazzio’s latest, Underwater Dreams, is appearing in many venues. AMC Theatres is providing free screenings of the film to student groups, and MSNBC and Telemundo both broadcast a version of it. With each of her films, Mazzio tries to make people think about issues and spark societal discussion, and she’s succeeding with Underwater Dreams, which broaches the hot-button issue of immigration. In July, she appeared on The Colbert Report to discuss the film. “I was nervous all day,” she says. “I was thinking, ‘This is an incredible opportunity. Don’t blow it.’”

The film even led to an invite to a science fair at the White House. While there, she received a mysterious text asking her to meet under the JFK portrait. “I didn’t know what was going on, but I thought it was something good,” she says. At the appointed time, President Obama strolled over to meet the gathered group. “It was an incredible privilege,” Mazzio says. “To have that kind of impact and exposure is really fantastic.”

In Maine, far from the White House, Hurley hopes her film will make an impact, too. Such a large number of people, more than 2 million, are incarcerated in the U.S., and their absence affects many families and friends in ways most unaffected people don’t understand. When Hurley talks about her film, she often hears from people who have their own painful experiences with the criminal justice system. They encourage her. “People resonate with the story, and they’re glad someone is telling it,” she says.

Working on her film during nights and weekends, Hurley continues the slow process of putting it together. Looking at the footage, which begins at her cousins’ sentencing and continues through their release, she relives the tough journey her family has endured. “I’ve been so proud of how our family handled it, of how it’s brought us together,” she says. “I feel like we can make it through anything.”