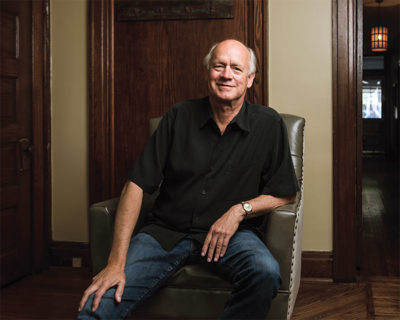

Jamie Kent ’09 on Broadway in Nashville

When Nashville singer-songwriter Jamie Kent ’09 launched his music career after graduating from Babson, he did what scores of aspiring musicians have done: He hit the road.

Since then, Kent has traveled many a mile and sung many a song. He plays his music, a warm, rollicking mix of country, rock, and folk, to audiences from coast to coast, performing 100 to 150 shows a year. Life on the road can be liberating, but it also can be repetitive and exhausting. Driving from one gig to another, he and his bandmates take three-hour shifts behind the wheel of an Econoline van, which is stuffed with gear. With no roadies to help them unload and set up before a show, they do it themselves, and when the concert is over, they load the van back up and hit the road again.

This grind, of packing and unpacking, of playing to strangers night after night, is traditionally how music careers are made. “If you want to do it full time, you have to hit the road,” says Kent. “That’s where you make money.” But as the digital age continues to upend the music industry, forever altering the way fans discover and listen to artists, many of the rules of the music game have changed. Hard work, undeniable songs, and a drive to play for people—these remain the basics of a successful life in music. But also needed nowadays, for not only singers on the stage but executives behind the scenes, is a nimble mindset, one that is comfortable navigating an industry in flux and open to exploring new opportunities.

Kent has done just that. Beyond extensive touring, he has started a small record label, has scored a couple of corporate partnerships, writes songs for a publishing company, organizes tours for other artists, and has brought together a dedicated group of fans, known as The Collective, that have provided him with funding and much-needed advice.

One thing he hasn’t done is sign a record deal, but his career is flourishing nonetheless. Kent’s last album, American Mutt, landed on Billboard’s top 20 country album chart when it was released in November. Kent heard the news while he was on tour, staying at a Holiday Inn in Tennessee. “I cracked open a great bottle of Scotch with my band,” he says. “It was a bottle I had been saving for a special occasion.”

Photo: Jason Myers

Kerry O’Neil, MBA’78, at the office of Big Yellow Dog Music in Nashville

The Door Is Open

One big conundrum has bedeviled the music industry for years: the internet. It allows for unparalleled access to music, but at the same time, making money off that access, or at least making the same sums of money as when the industry’s bread-and-butter was selling physical CDs, has proven elusive. As CDs and even music downloads continue their inexorable decline, the streaming of songs through subscription sites such as Spotify, Apple Music, and Google Play Music is increasingly the way fans hear music.

Kerry O’Neil, MBA’78, has witnessed these developments firsthand. He co-owns both a music business management firm, O’Neil Hagaman, and a music publishing company, Big Yellow Dog Music, that are based in Nashville. As he navigates the turbulent state of the industry, O’Neil adjusts and adapts. Gone are the days, for instance, when Big Yellow Dog Music would put together annual business plans. “Now, they’re not even quarterly. They’re just continuous,” O’Neil says. “Our style with dealing with change is saying, ‘The door is open.’”

O’Neil originally came to Nashville because he wanted to be a songwriter. He started writing songs in grade school, and as an undergraduate dropped out of college for a while because he was spending too much time on his songs rather than his studies. Arriving in Music City in 1980, he pursued songwriting during evenings and weekends while working at a CPA firm, where he built a client base of artists.

Surrounded by the city’s many amazing writers and artists, O’Neil came to two realizations. “The talent in Nashville, it’s the best in the world. What I found out was that I was just an OK writer,” he says. “It also became apparent that I had an ability to empathize with creative people. I understood their personalities.” So O’Neil drifted away from his dream of becoming a hit songwriter and embraced a career helping artists with their finances. His services were badly needed, as artists often entrusted their money to family members, many of them unqualified for the job. “People would get into all sorts of problems,” he says. “There were legendary IRS problems in Nashville back then.”

In 1984, O’Neil co-founded O’Neil Hagaman, and today it employs 50 people charged with handling the business side of music, whether merchandising, touring logistics, or record deal negotiations. “At any time, our artists have some of the top tours in the nation, some of the top albums,” says O’Neil, though he declines to mention any of his clients’ names. “We don’t as a rule do that. Their privacy is a primary goal.” The firm keeps a low profile and doesn’t even have a website. “We’re known as one of the quietest management companies,” he says.

O’Neil is more forthcoming about his work with Big Yellow Dog Music, which develops and promotes a group of 20 songwriters. Founded in 1998, the company has three main facets to its business, explains O’Neil. The first is traditional song publishing, in which Big Yellow Dog Music seeks artists to record its songwriters’ pieces. It also sets up songwriting sessions in which its writers compose with other artists. One of the company’s better-known writers is Meghan Trainor. While Trainor is a pop star on her own, having released the smash All About that Bass a few years back, she also has co-written hits for other artists, including Rascal Flatts and Jennifer Lopez.

Another department at Big Yellow Dog Music places its writers’ songs in TV shows, movies, and commercials. Over the past five years, 80 songs from the company’s writers have appeared in the TV show Nashville, while the films The Peanuts Movie and Smurfs: The Lost Village and TV shows Big Little Lies and Grey’s Anatomy also have featured Big Yellow Dog Music songs. With the instability in the music industry, these song placements represent a steady form of revenue and exposure for writers, says O’Neil. Last year, the company landed 400 song placements around the world.

The last facet of the organization’s business is artist development. Big Yellow Dog Music helps its artists grow their voices and build careers, a process that can take years. When signing a writer, the company is looking for people who have talent and something to say. It isn’t concerned with where their songs might fit in the everchanging marketplace. O’Neil compares the company’s thinking to that of a team in the NFL draft that picks a player for his talent, not necessarily for the position he will play. “The artists we work with, we try to find the ones who are so unique, people don’t know what to do with them,” he says.

For writers who also are performing artists, Big Yellow Dog Music looks to hone their sound. The company will bring artists and producers together, and it has its own record label, so it can record artists and put out their albums. To help them gain exposure through the variety of channels that music fans use to discover new music today, such as YouTube, social media, or streaming sites, the company tailors its approach to each individual. One of its artists, Jessie James Decker, used her strong social media following to propel downloads of her single, Lights Down Low. Another artist, Maren Morris, found great success on Spotify. “That doesn’t mean Spotify will break the next act,” O’Neil says. “Every artist is different. Every artist is on a different track.”

A Great Time for Artists

These many digital platforms are tools that musicians didn’t have a generation ago. “This is a great time to be an artist,” says Jon Ricci ’05, founder and lead singer of the hard-driving rock band Lansdowne. While streaming sites don’t pay high fees to most artists, Spotify and the like do allow them to release their music directly to consumers without the aid of a record company. A site such as TuneCore will distribute Lansdowne’s music to whatever digital platform Ricci chooses, and another site, SoundExchange, can collect his royalties. Lansdowne may have released two physical CDs in the past, but it has no intention of putting out more in the future, Ricci says, not when the band’s songs already have been streamed millions of times online. The digital age has changed the way music fans find new artists. They don’t have to go to a club, or turn on the radio, or even venture to one of the dwindling record stores. They simply can go online. “The discovery of new music has become frictionless,” says Ricci, who lives in Bolton, Massachusetts.

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Jon Ricci ’05 at the Brighton Music Hall in Boston

As a first-year student at Babson, Ricci didn’t intend to make music a career. His original plan was to become an investment banker. But he was inspired by his liberal arts courses, and he began singing and writing songs and spent many nights jamming in the rehearsal space in the basement of Park Manor Central. By the time he was set to graduate, the course of his life had changed. He was now an artist. “I wanted to give it a shot,” Ricci says. “I had to be true to what I was passionate about.”

Lansdowne formed in 2006, and its music has found a healthy audience. One of its more well-known songs, One Shot, has been viewed more than 4 million times on YouTube. The band has played well over 1,000 shows, including in the Middle East, where it entertained American troops. In Afghanistan, Ricci met a soldier who had the band’s name tattooed across his back.

Along the way, Lansdowne has taken a pass on not one, but two, potential record deals, as well as a slot on the TV show America’s Got Talent. At first glance, this may seem surprising, but Ricci says the terms of these opportunities weren’t right for the band. Because record companies no longer make as much money from music sales, they now seek additional sources of revenue with so-called 360 degree deals, which take a piece not only of a band’s music sales but also of its touring and merchandise earnings. That revenue is critical to a band’s survival, so the band decided to turn down the record deals.

As for America’s Got Talent, the show would have required that Lansdowne sign a long-term management deal that also took a piece of touring and merchandise sales. The price seemed too high for a TV appearance that would provide fleeting public attention. “It was hard to turn that stuff down,” Ricci admits. “I think it was the right call.”

Ricci isn’t opposed to signing a record deal in the future. A record company’s marketing muscle could prove critical given the right circumstances. And as the band continues to gain in popularity, it might be able to negotiate a deal with better terms. In the meantime, Lansdowne has three investors who provide the band with capital for making records and promotions. In return, the investors receive equity in the band or a piece of album profits, depending on the terms of their agreement.

Lansdowne should be back in the studio soon, ready to record a new batch of songs that Ricci has written. But the husband and father of two makes sure that life in a rock band doesn’t take precedence over his life at home. After missing his son’s first birthday because Lansdowne was playing a show, he vowed not to let that happen again. “You can’t miss those things,” he says. Lately, Ricci has kept busy with his venture, Prechorus, an app that centralizes the information needed to produce and promote a live event. Too often when bands play a venue, Ricci says, details about gear, lighting, promotional materials, and a host of other considerations can become lost in a slew of emails and written notes.

Prechorus puts all that nitty-gritty information in one central spot for easier access. Prechorus currently is being tested at two Boston-area venues, Brighton Music Hall and The Sinclair, and Ricci enjoys working on the startup, a much quieter pursuit compared to rock ’n’ roll. “I get as much out of building software as being on stage,” he says.

Photo: Jorge Oviedo

Camila Saravia ’04 in Bogota, Colombia

Plan for the Future

Offstage is where Camila Saravia ’04 operates. She is the CEO and co-founder of M3 Music, a management company working with Colombian bands. “There is a lot of talent in Colombia,” says Saravia, who lives and works in Bogota and also has an office in Miami.

While the growth of streaming has brought a somewhat steadier flow of revenue to record labels, Saravia says that innovative thinking is still in short supply. “People are very comfortable and not thinking in a more forward-thinking way,” she says. “If you are able to understand new opportunities, there are so many things to be done.”

M3 Music always is looking to the future with its clients. The firm sets specific career goals for them, something to which the more free-spirited musicians may not be accustomed. “We look at the artists not just as art, but also as a business,” Saravia says. “It’s been quite difficult to have musicians think that way.” M3 Music focuses a lot of its efforts on international strategy. If the goal is for a band to develop the U.S. market, for instance, M3 Music will set up a tour, or release a single and video, or book a date at a big festival and hope to land a primo time slot, one that isn’t too early in the day.

Saravia also works in music publishing, albeit with a tech twist. She is the cofounder and communications director of MusicAll, an online platform that connects companies, ad agencies, video-game producers, and others in need of music with a community of independent composers and artists. An ad agency that needs music for a commercial, for instance, can search MusicAll’s catalog of artists and songs. It also can request a custom-made song for the ad; if the agency wants an original up-tempo song with a Latin feel, a request is sent to MusicAll’s artists, who respond with ideas. Saravia says the site has proven popular with musicians. “There are so many independent artists,” she says. “It’s not easy for them to get their music heard.”

Saravia has always loved music. While at Babson, she was constantly attending concerts, typically about three a week, in Boston and New York City. Her mother recently found a scrapbook of her ticket stubs. “I can’t believe all the shows I saw,” Saravia says. Back home in Colombia after graduation, she worked for a producer of advertising jingles for a year and a half before heading to Barcelona, where she earned master’s degrees in both international marketing and the music business.

Returning again to Colombia, she became partner and vice president of a music management and promotion firm, SCP Music, which had a roster of 18 bands but only a small, harried staff. Saravia helped put on the bands’ concerts, which meant attending about 10 shows in an average weekend. “It was fun for a while in my 20s, but it was tiring,” she says. “That’s when I realized it was better to focus. Having so many bands wasn’t the way to go.” So in 2010 when she co-founded her own firm, M3 Music, Saravia decided to keep the roster small. Today M3 manages just four bands.

The most popular of those acts is Bomba Estereo, which tours all over the world and scored a catchy hit, Soy Yo, that is used in Samsung and Target ads. The song’s popularity was helped in large part by its fun video, which centers on an independent-minded girl intent on living life her own way. To create the video, M3 solicited ideas through a website called Genero, and a Danish director, who hadn’t even heard of the band, submitted the winning proposal.

When promoting a new song, M3 focuses not so much on radio as on social media. “Social media is important to us,” Saravia says. “It’s very effective. It’s very close to your fans.” For Soy Yo, M3 reached out to people popular on social media and asked them to post the video. The strategy worked. “After releasing the video, it was crazy,” Saravia says. “Everyone started posting it.” On YouTube, Soy Yo has been viewed more than 20 million times.

Road Warrior and Businessman

As much as social media and streaming are a great way to reach listeners, singer-songwriter Jamie Kent believes there is still no substitute for touring. Traveling repeatedly across the country, he may play a major market as many as four times in a year. Two of those appearances may be headlining shows, while the other two may be at festivals or as an opening act—gigs intended to expose him to a new audience. This summer, as he has done in the past, Kent and his band are opening on a number of dates for ’80s pop heroes Huey Lewis and the News.

Kent’s growing success as an artist can be measured by his choice of lodging while on tour. When he first started touring, Kent mainly slept on other people’s couches. Since then, he has graduated from couches to Motel 6, then to La Quinta, and now to Holiday Inn. “It’s a tangible level of growth,” he says. “Some bands love crashing on couches. I need my own bed at night.” He has yet to reach the ultimate symbol of success as a touring act: a bus. For now, Kent is content to be economical and travel in a van. “Money saved is money earned. Until you reach a certain level, you don’t need it,” he says. “I’ll run the numbers and see when it makes sense to get a bus.”

Kent believes so much in the importance of touring that he has partnered with First Note Play, an artist development agency. Together with First Note Play, Kent will develop tours for emerging artists. He envisions the tours as old-fashioned road shows, where several acts travel together, performing concerts but also doing community events such as school visits as they hit the same markets again and again to build a fan base. “A lot of artists don’t have the ability to book and promote a tour on their own,” Kent says. “This helps artists grow their own markets.”

Kent long has known that he wanted to make a living as a performer. He first picked up the guitar and started writing songs in high school. “I’m an only child,” he says. “On some fundamental level, I have to be the center of attention. That’s the Freudian diagnosis of my career.” When choosing colleges, Kent picked Babson over the Berklee College of Music because he wanted solid business skills, which so many artists lack.

He put those skills right to work. To fulfill a need for capital at the beginning of his career, Kent started a unique fan partnership he called The Collective. Fans provided Kent with monetary support and career advice, offering opinions on album artwork and which songs to push as singles. In exchange, Collective members received exclusive songs and free admission to shows. Eventually about 600 people signed up, and while Kent no longer asks for money from members, he continues to value their input. “My fans have a say in my career,” he says. “Data and insight from fans is more valuable than ever.”

Kent has formed other partnerships, landing Bose and Durango Boots as corporate sponsors. Kent receives sound equipment from Bose, boots and funding from Durango, and he plays events for both companies in return, showing off their products as he performs. “We’re evangelists for them,” he says. “I help promote their products in a cool way.”

Now he’s hoping to find a top-level manager, someone with strong industry connections who can “knock down doors.” Until then, Kent will continue to do what he always has done: work hard. When not on the road, he spends about 12 hours a day laboring on his career, whether booking shows, doing publicity, or writing songs for himself, other artists, or a publishing company that pitches his tunes to TV shows, films, and commercials.

Just like Jon Ricci of Lansdowne, Kent isn’t rushing into a record deal. Any such deal demands caution, for labels aren’t too forgiving of failure. “They will sink half a million dollars of promotion into a record, but if it doesn’t catch fire, that’s your chance,” Kent says. “I have spent too much time and effort building this thing to gamble it on one shot.” Ideally, he would like to sign a co-venture deal that partners the small record label that he started, Road Dog Records, with a major label. This would give him access to a label’s promotional arm and radio connections, though such a deal is still a ways off. “To do that, you’ve got to bring a lot of fans to the table,” he says. “We’ve got a lot of fans, but not to that level.”

Still, Kent has earned the right to be proud. He and his band are working musicians who have successfully grappled with the tumultuous times of a changing industry. “We’ve done some amazing things,” he says. “We’re making money, and we’re growing.”

Photo: Jason Myers

Jamie Kent ’09 in Nashville