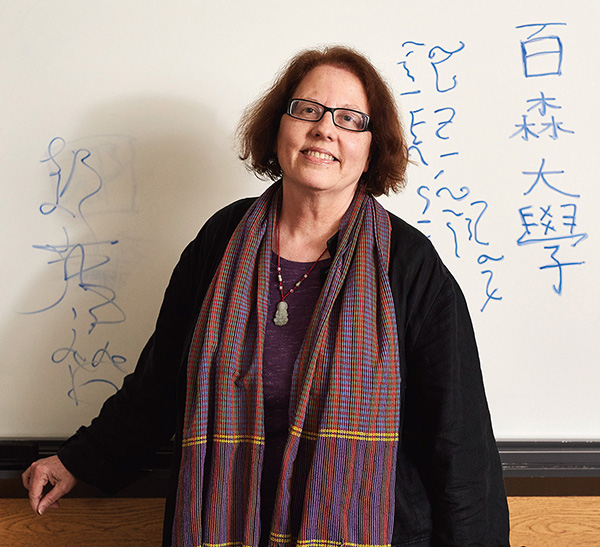

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Kandice Hauf, associate professor of history, enjoys learning about other cultures, and she hopes to inspire that same curiosity in her students. “We want them to be lifetime learners and global citizens,” she says.

For the first session of the new summer course she is teaching, Kandice Hauf brought in cookies and brownies to share with her students. Partly the treats were meant to fortify them. “I knew we’d be in this long class,” says the associate professor of history. “It’s more than three hours.”

But she also thought the students might need something sweet and comforting. The subject matter of her class, “Cambodia: Rebuilding Culture and Economy After Genocide,” is tough. “It’s heavy for a summer class,” says Hauf, who has taught at Babson for 25 years.

As many as 2 million people died in the Cambodian genocide, which was carried out by the brutal Khmer Rouge regime and lasted for four harrowing years during the 1970s. Hauf’s course examines the genocide and is particularly focused on its aftermath, on how a society finds the strength to rebuild and carry on. “How do people heal?” she asks. “How do they go on?”

Any traveling tips?

Don’t overschedule, and don’t be afraid to get out of your comfort zone. Go to the market one day, or just sit under a tree and watch the kids play and see how people go about their day.

How do you relax?

I want to do more reading. But once I start reading a novel, it’s hard to stop. I’ll turn around and it’s 6 a.m. I’m also trying to do more meditating. When I lived in Japan for two years, I would wake up at 4 a.m. and go to the temple and meditate for three, four hours.

A favorite book?

I try to read Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own every year on International Women’s Day. It’s a reminder to me of how far we’ve come in terms of gender equality, and not to take it for granted.

These questions haunted the well-traveled Hauf the first time she visited Cambodia in the late 1980s. She found a country still hurting. The Khmer Rouge were no longer in power, but Cambodia was in the midst of a civil war. Poverty and corruption were rampant, and Hauf saw many people missing limbs from the scores of landmines buried in the country. She wondered about the trauma suffered by the people she met. “There was a lot of internal pain that had not been addressed,” she says. “It was so staggering.” But despite all the horrors that had happened, Hauf found the Cambodians to be kind and giving. “People were so hospitable, so friendly,” she says.

Growing up, Hauf never imagined herself going to such faraway places. Until she was about 11, she lived on a farm in Wyoming with no indoor plumbing. “You look back with nostalgia,” she says, “but it was a lot of hard work.” It was also a precarious existence. “I remember one time with my dad watching the hail come down and destroying the whole crop,” she says. On the farm, Hauf learned to be self-sufficient and independent, to make do with less and be grateful for what she had. “It’s been a long time since I lived on a farm, but it’s still a large part of my identity,” she says.

Hauf’s mom later became a nurse, and Hauf assumed that she would go into medicine as well. But then as a senior in high school, she studied abroad in Sheffield, England, with the American Field Service. “It was eye-opening,” she says. “I suddenly realized there was a whole world out there.” The direction of her life changed. Instead of medicine, she studied international affairs at George Washington University, and an interest in learning other languages led the undergraduate to sign up for a Chinese language course. “It was the most different and difficult thing I had ever studied,” she says. From that language course, she soon grew interested in Chinese culture and history and decided to focus her studies on China. “I knew there was enough to learn to last a lifetime,” she says.

Hauf earned a master’s degree in Asian studies at the University of Hawaii, and her academic work took her to Taiwan for two years to study Chinese language and classical texts. “You can’t really learn about a culture unless you live there for a significant amount of time,” she says. Hauf went to Yale University for her doctorate in Chinese history, and because China wasn’t entirely open to scholars back then, she spent two years researching Chinese texts in Kyoto, Japan. She eventually traveled to China for the first time in the mid-1980s by serving as a tour group leader.

Over the years, the China expert became drawn to Southeast Asia as well. While at the University of Hawaii, she had grown close to a roommate from Laos, and Hauf studied the country’s language for a couple of years. As an American, Hauf also had an interest in her country’s involvement in Vietnam. Then in 1999, she adopted a baby daughter, Sara, from Cambodia. Sara is now in high school and has tagged along with her mother the last two times she has visited the country. Those trips have allowed her daughter, culturally an American but Cambodian by birth, to think about her identity and background. “It’s an interesting experience for her, to figure out how she belongs,” says Hauf, who also has helped build and support a school in rural Cambodia through a community organization of Cambridge, Massachusetts, residents.

With her summer course, Hauf wants students to learn about what happened in Cambodia. She urgently knows that genocide must not be swept under the rug of history, so the class also discusses other mass killings in Rwanda and Bosnia and during the Holocaust. “Hopefully, we can help this not happen again,” Hauf says.

Besides looking at Cambodian memoirs, histories, newspapers, and documentaries, the class took a trip to Lowell, Massachusetts, home of the second largest Cambodian community in the U.S. Students visited a Buddhist temple and a Cambodian community center, restaurant, and even a dance troupe, a welcome sign that Cambodia’s arts live on, despite the Khmer Rouge’s targeting of artists and musicians during the genocide.

Many of Lowell’s Cambodians, poor rice farmers in their home country, came to America as refugees. Hauf had her students interview them to hear their voices and stories, learning how immigrants work to make a new life and how the next generation is still adjusting to living in America. “I’m really trying to get students out in the community,” Hauf says, “so they can listen to someone other than me.”

The lessons of the class, and the stories of the Lowell Cambodians, weren’t always easy to hear, but the students listened and learned. Hauf says, “They’re aware you can’t shy away from this stuff.”