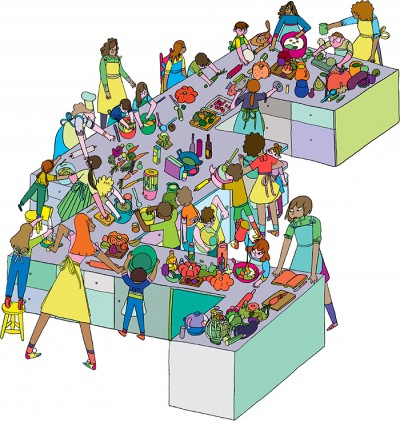

Illustration: Celyn Brazier

Karen Salvatore ’74 and Steve Dunn, MBA’93, both grew up in Italian-American families that loved to cook and gather for family dinners. Salvatore, whose mother was famous for her stuffed artichokes, says her parents expected their six children to be present for dinner. “You had to be sitting at the table at a certain time,” she remembers. “No phone calls. The TV was off, and it was family time.” Dunn and his family ate at his grandmother’s table every Sunday. “I grew up in a family where cooking was important and was done from scratch, but now so many people don’t have that,” he says.

Today Dunn and Salvatore both work to bring families back into the kitchen. They believe teaching cooking skills can start to solve the problem of childhood obesity in the U.S. The statistics are startling: Childhood obesity has more than doubled in children and quadrupled in adolescents during the last three decades, reports the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2012, more than one-third of U.S. children and adolescents were overweight or obese, which increases their risk of serious illnesses such as Type 2 diabetes.

Part of the problem, Dunn and Salvatore say, is a lack of familiarity with healthy, whole foods. “There are people who have never peeled a carrot, who have never handled raw chicken,” Dunn says. “Everything is either precooked or prepackaged and processed.” It’s a multigenerational problem, he adds. Many people are born into families in which parents and grandparents never cooked, instead serving frozen dinners, takeout, or fast food. Salvatore and Dunn are determined to help break that cycle.

Salvatore became particularly interested in health and nutrition in the late 1970s after reading about trans fats, the partially hydrogenated oils used in processed foods such as doughnuts, cookies, and chips. Scientists now know that trans fats dramatically increase heart-disease risk, but back then just a few researchers discussed this possibility. Their ideas alarmed Salvatore, inspiring her to learn more. For years, although she worked in communications at various companies, her passion was the field of health and nutrition.

Then in 2005, Salvatore established a nonprofit called Food and Truth, with a mission to inform, educate, motivate, and organize around issues related to food ingredients. While brainstorming ways to help, Salvatore remembered a pivotal personal experience: As a teenager, she founded an anti-smoking program that sent high schoolers to speak at elementary schools about the dangers of smoking. “I saw kids go home and apply pressure to their parents and get them to quit smoking,” she says. “That’s how I learned that going to children is an effective way to approach any problem.”

Teaming up with a community organization in Providence, R.I., she established a 12-week, after-school program called Fit2Cook4Kids. Funded by a $50,000 local grant, it offered middle schoolers a combination of chef-taught cooking lessons and fitness classes. Kids made foods such as salads, sushi, quiche, and fruit-infused waters, a healthy alternative to soda. They also took the recipes home to prepare for their families.

Because the grant required a job-readiness component, Salvatore and her team taught students how to sanitize their hands and dishes to state code (useful for future restaurant jobs). She engaged them in games that included public speaking and required that they address classmates about the meals they had prepared at home, building their confidence and thinking abilities. Salvatore ran two sessions of the course, reaching 48 children before the grant ran out.

To address the funding problem, she began offering the same program to kids through weeklong summer camps offered at multiple locations in Rhode Island. Funds from paying campers generated scholarships for kids who otherwise could not participate. Salvatore’s goal is to replicate Fit2Cook4Kids nationally, and she currently is seeking board members to guide the organization as it builds a sustainable model.

Like Salvatore, Dunn came to cooking mid-career. After working in finance, real estate, and high-tech, he moved his young family to France for two years so he could study at Le Cordon Bleu cooking school. An accomplished home cook, Dunn had completed a six-week culinary arts program in Boston and wanted to deepen his education. After the family returned to Massachusetts, Dunn launched a blog called Oui, Chef, which chronicled his adventures cooking with his three kids.

He also began volunteering for the Boston branch of Share Our Strength (SOS), a nonprofit devoted to eradicating childhood hunger. He currently volunteers with an SOS program called Cooking Matters, in which he and a nutritionist run six-week cooking courses in at-risk Boston neighborhoods. The work appeals to Dunn, who enjoys teaching (in his day job, Dunn works for America’s Test Kitchen, the company behind how-to-cook publications, TV shows, and websites) while giving back to the community.

The students are mainly young mothers of toddlers and are on food assistance. “We get moms when they’re young and can immediately impact the life of one or two or three young kids in their family,” Dunn says. Students spend half of each class learning about nutrition and skills such as meal planning, and the other half in the kitchen preparing dishes together. Popular recipes include jambalaya, tofu chocolate pudding, and vegetable frittata.

At the end of each class, students receive a bag of fresh ingredients used in the dishes prepared that night. “They get to go home and practice their cooking skills and introduce their family to new flavors,” Dunn says. “Nine times out of 10, their kids eat things that the moms never thought they could get them to eat. Husbands or boyfriends also get excited about class day because they know they’re going to have a chance to eat something new.”

Dunn says one of the biggest misconceptions he faces is that healthy food is too expensive. He disagrees and teaches students a different approach to meals: for example, cut back on expensive animal proteins by serving a few slices of steak on a big leafy salad instead of a big steak and small side salad. The Cooking Matters team also teaches students to plan meals over the course of the week, which saves time. The popular vegetable frittata, for instance, can be made on the weekend and cut up for fast, healthy weekday breakfasts. Parents can roast two chickens on Sunday and use the leftovers to make chicken tacos and chicken sandwiches later in the week. Having a plan prevents the 5 p.m. panic, says Dunn, when everyone is hungry and parents dial for a pizza.

As the women in Dunn’s classes experience success, some begin to change other aspects of their diets, such as giving up soda. Some start to lose weight. “It’s very rewarding to see people grow and see the benefits they get from participating,” Dunn says. “And a mom who’s a healthy eater can have a huge, positive impact on the developing tastes and eating habits of her child.”—Erin O’Donnell