Margaret Schlachter ’05

At first, you think they’re crazy. Sure, people like to work out, to push themselves, but what these alumni do is beyond the usual. It’s beyond rational. Why, you want to ask them. Why take your sports to such extremes?

But then as you watch them, their bodies full of grace and strength, you start to marvel at what they can do. They amaze you. They make you rethink the limits of what is possible. As they strain to do the improbable, you admire their guts and their willingness to ignore society’s conventions, even if you never quite stop wondering about their sanity.

Margaret Schlachter ’05 of Salt Lake City is one of these crazy, boundary-pushing, take-no-quarter alumni. For her, marathons aren’t tough enough. Later this year, she’s running in 50-kilometer and 100-kilometer ultramarathons. In June, she ran 60 miles, the equivalent of back-to-back marathons and then some, before foot issues forced her to drop out of the Peak 100, a 100-mile race.

Schlachter also competes in obstacle course racing, these muddy, adrenaline-fueled events that seem like something out of basic training, or some sort of masochistic workout, with runners scaling walls, climbing ropes, crawling under barbed wire, throwing spears, and jumping over fire. Some courses confront runners with a field of dangling electric wires, which can carry up to 10,000 volts. “It’s a big pop and a really intense shock,” Schlachter says. “The best thing to do is run fast through the wires and get in and out as quickly as possible.”

The most grueling obstacle races last for hours, even days, and resemble forced marches. Last year, Schlachter ran in the Spartan Death Race and lasted for 25 hours before dropping out. That’s 25 hours of physical tests, such as lugging a kayak and a 40-pound pack for miles, while willing herself to put one foot in front of the other. The year before, she lasted 21 hours and made it through some 150 obstacles in the World’s Toughest Mudder. Hypothermia and hallucinations ultimately forced her to stop. “I was upset, getting so close and not making it to the finish,” she says. “But I am going back to the World’s Toughest Mudder this year to slay that dragon.”

PEACE ON THE TRAIL

When thinking of Schlachter’s athletic feats, that question creeps up again: Why? Why couldn’t she just do an easy-going three-mile jog? Why feel the need to run for dozens upon dozens of miles and be shocked by electric wires? As intense as her races and training can be, Schlachter says she finds peace in all the miles. Depending on what races are coming up, she may run anywhere from 30 to 70 miles in a week, which includes a long outing every Sunday in the hills and mountains around Salt Lake that can last six hours or more. On top of that, there are many trips to the gym for strength training, but Schlachter finds it all therapeutic. “On long runs, you and you alone are on that trail,” she says. “It’s time to be by yourself, away from your phone. It’s you and your thoughts.”

Photo: Tobias MacPhee

To train for her long and intense races, Margaret Schlachter ’05 not only runs for miles upon miles around Salt Lake City, but she also regularly hits the gym for strength training.

Schlachter hasn’t always been such an uncompromising athlete. She may have played two sports at Babson, but she was goalie on the lacrosse team so she wouldn’t have to run around the field. After college, fitness wasn’t a priority. She coached high school lacrosse and alpine skiing, but she didn’t go to the gym and enjoyed wings night at the pub a bit too much.

Everything changed in 2010 when Schlachter entered her first obstacle course race. It inspired her. This was raw, messy time spent in nature away from life’s digital clutter. “These races speak to this primal need,” she says. “It’s very real. You’re in the mud. You don’t get that playing a video game.” Just like that, fitness was no longer an afterthought. More races soon followed, and she began tackling longer and more severe competitions. In just a short time, she became a consistent top finisher. In 2012, the Spartan obstacle race series ranked her the No. 5 woman in the world.

As racing and training engrossed her life, Schlachter made what seemed at the time to be a small decision: She started a blog called Dirt in Your Skirt about her running adventures. “It started as a personal blog for me for accountability,” she says. “At first my mom was the only one who read it. Then it started to grow.” Its popularity opened up entrepreneurial possibilities. By 2012, it was receiving about 1,000 hits a day and was the centerpiece of a business enterprise Schlachter started that focused on obstacle and endurance running. She was selling merchandise such as T-shirts and patches, and she was picking up sponsors.

Photo: Tobias MacPhee

With her blog and business growing, Schlachter was still working her day job as head of admission at a private school. It was a good gig, but with Dirt in Your Skirt and her training taking up so much time, something had to give. In July 2012, she quit her job. This was untested territory. Schlachter was the first woman to devote herself full time to obstacle racing. The move stunned friends. “I still have friends who think I’m crazy,” she says. A year later that decision is working out as Schlachter continues to expand her business and her profile. She offers coaching, runs a summer training camp, writes columns for the online site FitnessRX for Women, and is a contributing editor for Mud & Obstacle Magazine, set to launch in the fall. She also has a book coming out in 2014.

Through it all, she keeps moving. There are always more miles to go. When her body aches, she’ll acknowledge the pain in her mind and push on. She’ll think, I can go a little farther, and then, a little farther after that. “Physically, our bodies can take a lot,” she says. “People say this, but it really is all mental. It is really amazing what the brain can do.”

She remembers trying to climb a rope in a race, her hands cramping after swimming through a chilly pond. “It was so cold. My body froze,” says Schlachter, who somehow compelled herself to keep climbing. “You just got to go do it. You got to dig a little deeper and find out what you can do.”

A BETTER SELF ON THE MAT

Brent Earlewine, MBA’10, can inflict a lot of pain. Not that he wants to. He’s a ninth-degree black belt in Budo Taijutsu, a martial art that traces its roots back some 2,500 years to samurai in Japan. Those who practice it are known as the Bujinkan, which translates loosely to “house of divine warrior.”

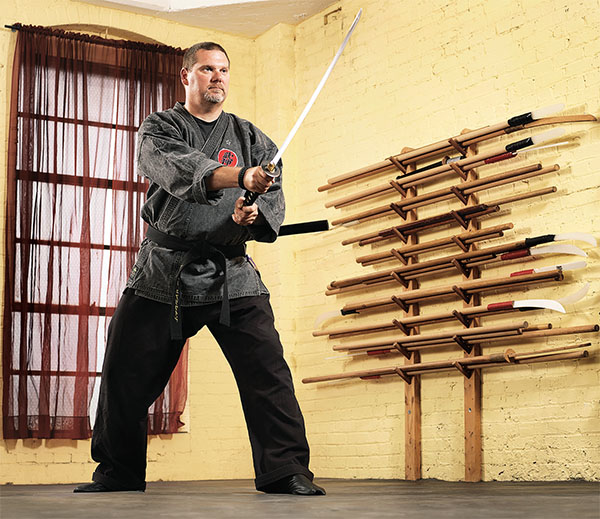

Photo: Mike Basher

Brent Earlewine, MBA’10, is a practitioner of a battlefield art that requires strength of body and mind.

Much like Schlachter’s running, Earlewine’s martial art requires strength of both body and mind. His training is cerebral. Ask him what he’s studying, and words seem inadequate. “I’ll give you an answer, but I’m not sure you’ll understand,” Earlewine says. Check out his Twitter page, and he sounds almost like a Zen master. “You have to learn the structure before you can throw away the structure,” reads one.

A 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike ride, and a 26.2-mile run. These daunting distances make up the Ironman triathlon, and they are the numbers that Nancy Gomes ’93 ponders in her mind. Could she do it, she wonders. Could she handle these distances?

The Franklin, Mass., resident already ran a half-Ironman last year on a tough 97-degree day, one in which she constantly doused her head with ice water. “It was hot. It was humid. It was gross,” she says. Despite the heat, the 70.3-mile race (half the full Ironman distance) was a great experience, save for the running. Pounding the pavement isn’t her thing. “I enjoyed the bike and swim,” she says. “I maybe enjoyed the first two miles of running. Your legs feel like bricks.”

To further test herself, she’s participating in two more half-Ironmans this summer. If those go well, she’ll sign up to do a full Ironman in 2014. From the relentless workouts to the loss of downtime to the potential to annoy even the most patient of spouses, Gomes understands the competition is a major commitment. It takes a solid year of training. “You have to go all in,” she says. “I think I know how much suffering is involved.”

Gomes played soccer in high school and at Babson, but she wasn’t always such a serious endurance athlete. About five or six years ago, a friend mentioned a sprint triathlon, a shorter race that serves as an introduction to triathlon competitions. She signed up for it, even though she had to learn how to swim, and soon was hooked. Longer races have ensued, and her training regimen has grown rigorous. In a typical week, she’ll work out 12 to 14 hours. That means training most days both before and after work, each session lasting one to two hours. Longer weekend workouts follow. “It makes you feel positive to push yourself,” she says. “I love the challenge. You could say it’s addictive.”

Triathlons also are a mental test. Before a competition, she thinks of what can go wrong—a leg cramp, a flat tire—and how she will handle it. As she races, she concentrates on keeping her pace steady and not going too fast. “You have to hold yourself back,” she says. “You have to stay in the moment. It’s a challenge to stay focused.” To keep going mile after mile, she thinks of Boston Children’s Hospital, the charity she runs for. She thinks of those who supported her. And she thinks of the finish line, which will be a welcome sight if she ultimately races in an Ironman. “People think we’re crazy, but that feeling of crossing the finish is very motivating,” she says. —JC

To illustrate the importance of mental vigor to Budo Taijutsu, the Pittsburgh resident talks of the astonishing sakki test, a requirement for all the art’s practitioners hoping to earn their fifth-degree black belt. The test, which is administered only in Japan, consists of one challenge. The test takers kneel on the floor with their eyes closed, and behind them stands the soke, or grandmaster. He holds a solid wooden sword above their heads. “It’s a pretty version of a baseball bat,” Earlewine says. Without warning, the soke brings the sword down, and the test taker must sense it coming and duck out of the way. “Trust me, you can’t hear it,” Earlewine says. “You have to be in the moment.” Earlewine recalls kneeling, concentrating, waiting for the soke to act. Then came an otherworldly signal. “I heard him in my head, ‘I’m about to cut. You need to get out of the way,’” says Earlewine, who did just that and earned his belt.

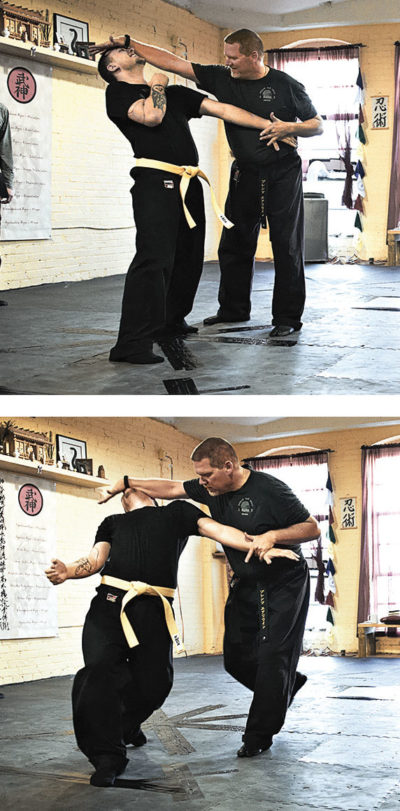

That’s a jaw-dropping feat, one that’s hard to believe, but Budo Taijutsu isn’t simply about mental acrobatics. It’s also about brute force. Unlike other martial arts that emphasize sport and exercise, it’s designed for one main purpose: to hurt people. Budo Taijutsu utilizes throws, hits, takedowns, and joint locks, which painfully bend the body in a way it’s not supposed to go. Swords, spears, and staffs also are used. “It’s a battlefield art,” says Earlewine. “It’s a zero-sum game.”

Earlewine began studying martial arts when he was 17. He’s now 44. “I couldn’t imagine not doing it,” he says. “It’s not a hobby. It’s become a part of who I am.” As a teenager, he wanted to be a “badass,” and the exotic nature of martial arts intrigued him. In time, though, those allures faded. He first studied Tang Soo Do, a Korean martial art, but he grew disillusioned that it was superficial, that it didn’t offer anything deeper than sweating on a mat.

Photos: Mike Basher

He took up Budo Taijutsu in 1996 and has been at it ever since. Such longevity is unusual. Earlewine estimates that out of every 100 people who start martial arts training, only two or three will earn a first-degree black belt. Of those, only one in 10 will make it to second degree. Around the world, fewer than 200 people are rated as highly in Budo Taijutsu as Earlewine, who is only one belt away from reaching 10th degree, the highest level. He’s so highly rated that to train, he travels every four to six weeks to where the most senior instructors live. He goes all over the country, and he also has taken three trips to Japan to study with the soke.

Hearing about Earlewine’s commitment, the same question pops up: Why? Why is he still at it? Doesn’t he already know enough to defend himself? “I’ve known how to physically handle myself for a long time,” Earlewine says. “It’s no longer the main reason I do this. When you know you can truly hurt someone, you wonder, is it worth it?” As part of his training, he has learned how to project his inner strength and confidence. “You gain a sense of presence,” he says. “People realize they shouldn’t mess with you.”

For Earlewine, studying martial arts has been transformative. Similar to how Schlachter finds fulfillment on the trails and in the gym, he finds it on the mat, in the flow and grace of his actions. “There’s peace in the movement,” he says. “It changes you and how you think.” As he has earned higher and higher belts, Earlewine has become someone not afraid of challenges, someone who’s an example to others, a teacher. While he works as a manager at Avaya, a telecommunications company, he and his partner operate a dojo, or training facility, called Pittsburgh Bujinkan Taka Seigi Dojo. The pair originally had started a website to document their training, but the site found an audience of people looking for instruction. The two had never planned on running a dojo, but after first offering a popular class at a local community center, they opened their facility in 2003.

At the dojo, Earlewine watches the new students who come in with the chip on their shoulders, the ones who want to be tough, as he did when he started. Slowly, they mellow. That chip disappears. “It’s not about beating someone up,” Earlewine says. “It’s about being the best version of yourself.”

CHALLENGES IN A KAYAK

Dave Lamoureux ’89 is a fisherman, of a sort. He has his unique way of fishing for bluefin tuna. It’s a bit, well, different. Waking up at 3 or 4 a.m., he drives to Provincetown, Mass., on the tip of Cape Cod. There he puts his kayak, named Fortitude, in the water and proceeds to paddle out into the open ocean. After about 90 minutes, he reaches his fishing spot, which is two miles or so offshore. With his line in the water, he waits for a bite from the big fish. It can’t be missed. “It stops the kayak dead,” he says. “Your body snaps. It’s like being in a car and slamming on the brakes.”

Photo: Tom Kates

Dave Lamoureux ’89 says tuna is the toughest, most powerful game fish.

Then comes what Lamoureux calls a “Nantucket sleigh ride,” as the fish pulls his kayak along at speeds of up to 20 mph. Reining the fish in can take as long as four hours. “You have to tire the fish out before he tires you out,” Lamoureux says. If he keeps the fish he catches, he then has to tow it back to shore, a hard and slow process. Add it all up, and he paddles 15 to 20 miles in a typical outing. While on the water, Lamoureux survives on 5-Hour Energy drinks.

Lamoureux’s unconventional fishing technique may be exhausting, but it’s also effective. He holds the record for the biggest bluefin tuna, 157 pounds, caught unassisted from a kayak, and his antics have been featured in The New York Times and on Animal Planet’s Off the Hook: Extreme Catches TV show. “I am the only person in the world who fishes like this for bluefin tuna,” Lamoureux says. “It’s dangerous. That’s why I’m the only guy in the world who does it.”

One thing making it dangerous is the fish he’s chasing. “Tuna is the toughest game fish,” says the Cambridge and Yarmouth resident. “A tuna is like hooking on a freight train. It’s a bull. It’s powerful enough to drag me and the kayak to the bottom.” Then there’s the matter of great white sharks. The water is full of them, and he has had several scary encounters. Once a great white zigzagged through the water trailing Lamoureux, who was dragging an 80-pound tuna catch back to shore. He actually had no idea the shark was there, and only found out later from a park ranger who was watching him through binoculars.

Photo: Tom Kates

Dave Lamoureux ’89

Another time, he paddled out early in the a.m., the morning’s calm broken when a great white attacked a seal pup about 30 yards away, the shark’s jaws clamping down with “awe-inspiring power.” At first, only the great white’s mouth was visible, but then the rest of its body rose to the surface. Lamoureux estimated it was 14 feet long. “I wasn’t putting a tape measure up to him,” he says. “It was bigger than my 12-foot kayak.”

At this point, that familiar question is begging to be asked: Why? Why paddle out into the vast ocean and worry about sharks? Why doesn’t he fish off a bridge, beach, or boat like everyone else? “I would fish off a bridge, but I would be bored,” Lamoureux says. “I get bored with things that are easy.” A lifelong fisherman, he took up kayak fishing in 2009, just one in a long line of extreme sports that Lamoureux has tried. “I was a rock climber till I got too heavy,” he says. “I was an extreme skier until my knees went.”

Lamoureux insists he’s not an adrenaline junkie. “I’m a challenge junkie,” he says. “I take on the challenge and mitigate the risk. It’s about risk management.” To manage the considerable risks, Lamoureux goes to great lengths. He has become an expert on the weather, so much so that commercial fishermen, many of whom were skeptical when he started kayak fishing, will ask him about forecasts. Being stuck in a kayak during an ocean storm would not be fun.

Photo: Tom Kates

Dave Lamoureux ’89

He also carries 50 pounds of gear, much of it safety equipment, including a life jacket, dry suit, VHF radio, cell phone, flares, signaling mirror, whistle, knives, fog horn, GPS, compass, and dive fins. If he ever capsizes, he doesn’t want to rely on the Coast Guard to rescue him. “If you do something that is risky and don’t plan for a self-rescue, that’s irresponsible,” he says. As for his fishing equipment, it’s all made of titanium, which is impervious to the corrosive effects of salt water. Lamoureux is co-founder and CEO of Amalgamated Titanium International Corp., which developed a process for producing more affordable titanium. Tired of his fishing paraphernalia always rusting, Lamoureux had titanium equipment made for himself, and that led to Fortitude Fishing, a subsidiary of Amalgamated that sells reels, harpoons, hooks, and the like. As with Schlachter’s website and Earlewine’s dojo, Lamoureux’s obsession brought about a business opportunity.

The three extreme alumni, though, aren’t alike in all ways. Unlike Schlachter and Earlewine, Lamoureux doesn’t find much peace in his sport. At first, that may be surprising. As he paddles, Lamoureux is alone with the sea, surrounded only by the sounds of birds and water. Seems tranquil, but it’s not. He is constantly thinking, about the tide, about the weather, about signs of tuna, about sharks. Moments of serenity are fleeting. “There’s nothing calmer than when I paddle out for the first time every season,” he says, “but then I’m thinking if a great white is coming to eat me.”