Illustration: Miguel Porlan

The hands-on exercise was part of a class called “Introduction to Sustainability,” offered jointly by Babson, Olin, and Wellesley colleges. Students from all three institutions can earn a certificate in sustainability; students may opt to emphasize different aspects of sustainability, depending on their interests, but the co-taught course, part of the Babson-Olin-Wellesley (BOW) Collaboration and helmed by one instructor from each school, is one of the shared requirements.

The course is intended to provide a philosophical, social, and practical framework for the study of sustainability, but its centerpiece is the energy audit. Working in groups, students spent several hours at local houses whose owners, members of the colleges’ communities, volunteer for the task.

As the students roamed the house, aiming their infrared camera at corners and windows, Olin instructor Tess Edmonds talked them through the tasks. When the camera’s display showed areas of blue, students recognized heat-loss trouble spots. “It’s so blue in there,” Edmonds said of a drafty, disused bedroom. “There’s probably some conductive energy loss through the seam in this corner.”

Later, the group wrestled into place a blower door, essentially a large fan used to change air pressure in a building and measure its airtightness. They surveyed the owners about their energy usage and took one last set of measurements before departing. About two months later, they gave the homeowner a detailed report about their findings and recommendations for improving the house’s efficiency, from unplugging unused appliances to installing a solar hot-water heater.

Why such a deep dive into the nuts and bolts of a home-energy audit? The idea, say the instructors, is to take students from the big picture to specifics, as well as to provide a microcosm of certain sustainable practices that can have a broad impact when enacted on a larger scale. “We always try to make the point that this is a very complex problem, sustainability. There are no easy solutions,” says Dave Chakraborty, the instructor from Wellesley. “But we also have to be optimistic and take concrete steps, however small, to change the system, and the home energy audit is just that.”

Jacob Allread ’20 hadn’t thought much about sustainability before coming to Babson. But a course on nature and the environment—chosen, he says, “at random”—piqued his interest. He enrolled in the intro course and now plans to earn the sustainability certificate. This class, he says, has been eye-opening: “It’s not just about the environment. Society also needs to be sustainable; the economy needs to be sustainable.” Much of the study of sustainability, he says, is abstract. But “being able to see and almost touch what was going on in the house during the audit was incredibly valuable.” He also appreciated being part of a BOW class. “Olin and Wellesley students bring a whole different dynamic to the table, which I love.”

Course instructor Michelle Graham, a lecturer in Babson’s Arts and Humanities Division, speaks of a “paradigm shift” in the approach to sustainability—one that will require new ways of doing business across the board. Of her students, she says, “Their generation grew up watching the Arctic ice melt. They see the evidence before their eyes. It’s not just academic; this is their future.”

Adds Olin’s Edmonds, “If this class creates more curiosity about different ways of looking at these really complex issues—for me, that’s success.”—Jane Dornbusch

]]>After graduating from Babson, Heidinger headed to New York City to work for a small consulting and money-management firm that specialized in socially responsible investing. But she decided the fit wasn’t right, and within six months Heidinger accepted a position with FremantleMedia, a global television production company responsible for shows such as American Idol, The X Factor, and The Price Is Right. Her job involved supporting business that was generated by programs such as product placement. “The Coke cups on the desk that Simon Cowell and the other judges drank out of on American Idol? That was a deal that our team did,” Heidinger says.

She spent six years with the company, first in New York and then, looking for a warmer climate, in Santa Monica, California. Heidinger next took a special-events position with DreamWorks Animation, arranging movie premieres, global film launches, and company appearances at the Cannes Film Festival and trade shows. “It was an incredible company to work for, but I didn’t care much about the work I was doing,” she admits. “I was never star-struck. That made the 16-hour days really difficult.”

As her 30th birthday approached, Heidinger decided to fulfill a longtime dream by taking a three-week trip to Kenya. She went on safari and then spent a week in the slums of Nairobi, where she helped break ground for a women’s clinic and volunteered in an orphanage for children with addictions. The experience led her to question her career. “This world is so crazy. There are so many people in need, and here I was working in this posh job—but I was not helping anyone,” she recalls. “I was just making the wealthy wealthier and celebrating celebrities who already had everything they needed.”

At the end of her trip, she returned to California and resigned from her job. But perhaps even more surprisingly, she also realized that she wanted to break the pledge she had made as a teenager and head back to Buffalo. Her periodic trips home had intrigued her. She was discovering new restaurants and development in old neighborhoods, and Yahoo had opened a data center and customer-care facility. “More and more, you’d hear that some classmate from high school had moved back,” Heidinger says.

Around Labor Day in 2014, she packed her Mini Cooper and headed east, uneasy that she was moving back in with her parents and had no job or health insurance. But just a few months later in March, she was hired as director of special events and programming for 43North, a position that means serving as one of Buffalo’s chief cheerleaders.

In 2012, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo had unveiled the Buffalo Billion project to spur economic growth and job creation in the region. One of the initiatives included an annual $5 million business-plan competition that requires winning companies to move to Buffalo and stay for at least one calendar year. Heidinger’s employer, 43North, runs the competition, now in its fourth year. Each October, eight winners are selected and must establish operations in Buffalo by January 1. Heidinger helps employees of those companies settle into the Buffalo area and arranges entertainment itineraries that companies can use to impress important out-of-town visitors. “We recognize that if companies don’t love Buffalo, they’re probably not going to stay,” Heidinger says. “I do anything I can to open their eyes to what’s going on here and help them fall in love with Buffalo.”

Photo: Matt Wittmeyer

Colleen Heidinger plans to live on the second floor of the building she is renovating and open her own events business in commercial space on the ground floor.

Along the way, Heidinger appears to have fallen in love with her hometown as well. “The cost of living is unbelievable,” she says. “There’s no traffic. We have great dining. We have NFL and NHL teams, we attract all the shows and big bands, and after a night out you’re still able to get home in 12 minutes.”

She recently entered the Buffalo real estate market by purchasing a 1914 building in a revitalized area called Larkinville. She is rehabbing the building, planning to live on the second floor and open her own events business in a commercial space on the first floor. “I often tell kids that I mentor, ‘There’s no better place to fail,’” Heidinger says. “If this real estate project blows up, I didn’t use my whole savings account or sign my life away. If I did this in Greenwich Village, you can bet it would be all my money. If you have an idea you want to test out, or need to hire 20 people, Buffalo is a good place to do it.”

Still, coming home has had its challenges. Heidinger enjoys being part of a small, tight-knit community but notes that dating was tough at times. (She now is seeing “a very great guy.”) She also is grateful for Babson friends scattered around the country, including those in New York City and Boston who give her a regular place to land when she needs a big city fix. “I do need to get out of here sometimes,” she says. “But then I’m very happy to come back.”

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Dan Dalet ’03 co-founded SoloCoco in his homeland of the Dominican Republic to help the economy and provide employment for locals, many of whom are single moms.

Hope Through Work

Growing up in the Dominican Republic, Dan Dalet ’03 and his two brothers lived a comfortable life. They attended good schools, their father worked for a bank and later the auto company Fiat, and their mother was a portrait photographer. As a surfer, Dalet took full advantage of the white sand beaches and amazing weather.

But Dalet also knew the DR’s strong GDP and popular tourist resorts didn’t tell the whole story of his country. “If you drive 10 miles in the opposite direction of those beaches, you find yourself in poverty and underdevelopment,” he says. “As a youth, I always had the idea that someday I would come back to my country and add value.”

First, he traveled to Babson to earn his undergraduate degree. Intrigued by the world of finance, he worked for a private bank in Florida after finishing his studies, and then he helped establish a Boston-based hedge fund comprising entrepreneurial companies. But around the time of the economic collapse in 2008, Dalet began rethinking the long hours and stress of his job, and he couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that his work wasn’t making a lasting impact on the economy or people’s lives.

Dalet began to wonder if it was time to head home. He imagined doing his part for the local economy by launching a company, and he was casting around for ideas when a conversation with his parents grabbed his attention. They were talking about the health benefits of coconut oil. Initially, Dalet was skeptical, but then his uncle, a physician, chimed in, saying that he thought new research about coconut oil was compelling. It was the proverbial lightbulb moment. “I thought, we’re surrounded by coconuts here,” Dalet says. “Why aren’t we making very high-quality, organic coconut oil?”

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Dan Dalet (left) at SoloCoco

Historically, the Dominican Republic has harvested coconuts and exported them as produce or raw material. But Dalet imagined something new: processing the coconuts and turning them into high-quality products before export. So in 2011 he and his wife moved to the DR, and Dalet dove in, experimenting with the production process at a manufacturing facility he established in a rural area 3 1/2 hours from the capital. A year into the venture, however, Dalet hit a significant roadblock. When trying to recruit workers, he discovered that few were available, because most had left the rural area to find work in the city.

Undaunted, Dalet started over. This time he partnered with his cousin Abel Gonzalez, opening a new plant in San Pedro de Macoris, a city with a population of about 195,000 in the southeast region of the island. As they prepared once again to bring on staff, they advertised a willingness to hire applicants who lacked typical experience but demonstrated promise and a desire to work.

One morning in November 2014, they drove to their plant to interview potential employees. What they encountered stunned them. “There was a line of more than 250 women waiting outside,” Dalet remembers. Most were single mothers in their mid-20s, raising three to five children on their own. Many never had attended high school. One woman told Dalet that she was willing to do anything to feed her children, but no one would hire her.

“The sense of despair and hopelessness impacted us profoundly,” Dalet recalls. Although he always had been aware of income disparity in the DR, Dalet still was startled by the severity of the poverty and the lack of options for these women and their children. He and his cousin saw their upbringing and access to education with new eyes. “That day changed us as human beings,” he says, “and changed us as entrepreneurs.”

Running a successful company would no longer be enough. Dalet and Gonzalez made a strategic decision to launch as a socially conscious venture designed around the well-being of its workers. They called their company SoloCoco, which translates to “just coconut” in English. (“Just” is intended as a double-entendre, meaning both “simply” and “fair,” Dalet says.) They hired more women than they initially planned and created a flexible work schedule that would allow employees to work as little as one or two days a week.

Dalet has seen statistics suggesting that a high percentage of children in the Dominican Republic are born to single mothers. These children are more likely to experience poverty and drop out of school, he notes. Many don’t attend school because they lack basic resources, such as school supplies. Those who do attend often experience frequent illnesses and absences because of a lack of sanitation and basic health care. These factors put high school graduation out of reach for many children of single mothers, Dalet explains.

Faced with these daunting statistics, Dalet worked to earn certification by the Fair Trade Sustainability Alliance, a New York-based organization that oversees the well-being of a company’s workers. In addition to offering his workers health care, Dalet partnered with FairTSA to set up a co-pay fund to help with costs not covered by insurance and a fund to cover the cost of school supplies for employees’ children. Another initiative, driven by SoloCoco staff, focuses on employee housing and sanitation. Last summer, the company built its first concrete house, complete with indoor plumbing, for one of SoloCoco’s single-mom employees.

The business is growing. SoloCoco now sells its coconut oil and body-care products in more than 10 countries, and they are carried by 75 Whole Foods stores in the Northeast U.S. This growth comes with challenges, however. “Our biggest problems right now are cash flow and capital requirements,” Dalet says. “It’s harder to find startup funds in the DR, and we can’t borrow money because interest rates are high and lending for small businesses is rare. We’re all self-funded at this time.” Others in Dalet’s family contribute to the business. His wife is a certified natural skin-care formulator, and she develops the company’s organic, personal-care product line. When Dalet’s father retired from Fiat two years ago, he began working for the company in an administrative role.

Dalet says he is motivated daily by what SoloCoco means for his employees. “The most important reward has been seeing the transformation of these families and these kids,” he says.

He and his cousin hope their success motivates more entrepreneurs to come home. “If we do a good enough job with this, it’ll inspire more people to come back and build on our trails,” Dalet says. “This country doesn’t need one SoloCoco. It needs 1,000 of them.”

An Agent of Change

Alex Souza ’09 was born in Mexico City. Although his family moved to San Diego when he was 2, they returned to Mexico City in time for him to start high school. Part of the motivation around the moves was an opportunity to experience other cultures. “Our parents really wanted us to go out there and see the world,” Souza says. “If there was money to spend, we spent it on travel.”

Photo: Alicia Vera

Alex Souza ’09 founded Pixza in Mexico City to help homeless youths change their lives.

His mother, Alejandra, also instilled in Souza and his sisters the importance of helping those in need, bringing them to volunteer with Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity in Mexico City. A life coach, Alejandra taught her children that the best way to help people is by offering them tools to reshape their lives. “That’s always been a big thing in my family, to recognize that you are an agent of change,” he says. “If you want to change the world, you cannot sit around and wait for things to happen.”

When the time came for college, Souza chose Babson for its focus on entrepreneurship and the chance to live in a new place. His college years included a semester at sea and opportunities to study abroad at the London School of Economics, as well as in Uganda and Hong Kong. After college, he returned to Africa with fellow Babson alumni to start an English-language school and management-training program in Rwanda. The program included an initiative that helped underprivileged students; for every 12 students who paid full tuition to the program, one student attended tuition-free.

After successfully launching the business in Rwanda, Souza wanted to build his knowledge of social and economic development. So he sold his stake and enrolled at Columbia University for a master’s in public administration and development practice. While in school, he spent a semester in Bhutan and introduced a program that measures national well-being. After graduation, he moved to Rio de Janeiro to work with the Inter-American Development Bank, which aims to reduce poverty and inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean through financial and technical support; Souza helped establish sports programs for youths living in Rio slums.

When his contract with the IDB ended, Souza turned his attention to home. “I had already helped solve issues outside my own country and learned so much,” Souza says. “But after working in Rwanda and Uganda, Brazil and Bhutan, I decided to go back to Mexico to see what I could do here.”

Photo: Alicia Vera

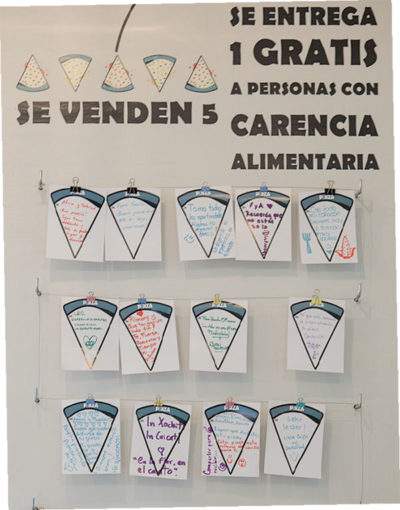

Sign inside Pixza

Souza felt drawn to the plight of Mexico City’s homeless teens and young adults, many of whom are born into homelessness. Hoping to intervene before these youths became adults, Souza began to think about ways to use his Babson-earned entrepreneurial skills. While at grad school in New York City, he had craved a Mexican food known as huarache, which is made with blue corn, and he theorized that the ingredient might make a tasty pizza crust. The idea resurfaced when he decided that a restaurant would make an ideal work experience for homeless youths. Souza spent four intense months developing a blue corn pizza crust that could be topped with traditional Mexican ingredients, including grasshoppers and zucchini blossoms. He called his restaurant Pixza (based on a common Mexican pronunciation of “pizza”), and envisioned “a social empowerment platform disguised as a pizzeria.”

For every five slices sold at the restaurant, the Pixza team donates a sixth slice to youths at a nearby homeless shelter. They deliver all the slices on Sundays. But Souza aims to do more than feed the teens. “It starts with a slice, because that’s a good reason to come together and talk,” he says. “But we want to move on to something bigger.”

Based on his previous experiences with social empowerment programs, Souza developed a detailed, multistage intervention that he calls “The Route of Change.” When youths at the shelter receive their first piece of pizza, they also receive a bracelet, which is punched each time they accept a slice. After the fifth slice, they must complete a small volunteer project of their choice, such as delivering a slice of pizza to a friend. “Instead of just being willing to receive, they have to be willing to give as well,” Souza says.

Kids who don’t complete this step are out of the program. Those who finish receive five more slices and a chance to complete a larger volunteer project. If they hit that milestone, they advance to receiving a shower, haircut, doctor’s appointment, T-shirt, and daylong life-skills course. When they complete those steps, they receive a formal job offer at Pixza, a regular salary, and a job title: Agent of Change. They get restaurant skills training and their own life coach. “The coach helps them develop a personal and professional plan,” Souza says. “Since they’ve been living on the streets, many don’t have the ability to dream.”

Professional life coaches, including Souza’s mother, usually donate time to work with the teens. In the final stages of the program, Souza and his team help participants find housing. Since Pixza launched in 2015, it has graduated and employed 23 kids, including four who have moved into housing. The entire program is funded by restaurant revenues.

Souza has opened a second location but has learned that restaurant management isn’t his strong suit, so he currently is seeking a business partner with this expertise. “I want a partner who actually loves to run restaurants, so we can open up many more locations, and I can focus on the part I’m better at, which is the social empowerment aspect,” Souza says. One day, he hopes to open an institute where he can train homeless youths for a range of roles in the food and beverage industry.

Pixza’s success has taught him the power of business to address social problems. “You can make that an objective from day one,” he says. “It’s amazing how you can use a for-profit business to make a difference.”

Photo: Greta Rybus

Jessica Wright ’11 lived in Ireland for two years, but she knew she would return to North Conway, New Hampshire, some day. Now she’s a local food systems advocate and part of a group that encourages young adults to settle in the area.

Building Communities

Jessica Wright ’11 adored her childhood in North Conway, which is in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. She was 10 when her family moved to this village, popular with tourists, skiers, and hikers. Her mother and stepfather opened the Metropolitan Coffee House in a historic building that once held North Conway’s bank. Wright and her sister spent much of their teen years working at the family business. “It evolved into this really cool community space where people would come and go for open mic night,” Wright says. “Our friends would come for teen night. Given the small town, and the central location, we knew everyone in town.”

While at Babson, however, Wright became interested in travel. She spent a semester in Ireland at University College Cork and fell in love with the place. After graduation, Wright interned with the Family Equality Council in Boston and considered law school, but she decided instead to return to County Cork in Ireland. She spent two years working as a nanny, traveling, playing rugby, and volunteering on organic farms. Those volunteer stints fueled Wright’s passion for farming and locally grown food.

As Wright prepared to leave Ireland, she applied to law school, but life as a lawyer still didn’t feel quite right. Then she found a master’s program at Vermont Law School focused on environmental law and policy. It would prepare her for a career in advocacy, and, apart from occasional on-campus courses in Vermont, she could do most of the work online, clearing the way for her to return to North Conway. “Coming back from Ireland, I just knew that I wanted to be here,” she says. “I love being in the mountains and an hour from the ocean. I love the snow and skiing. There’s nothing like hiking in the White Mountain National Forest in the fall, when the trees look like they’re on fire because the colors are so phenomenal. And I think my favorite part is that the Saco River runs right through the heart of where we live.” Wright takes frequent hikes along the water and ends hot summer runs with a dip in the river.

As she wrapped up her master’s degree, Wright began volunteering for the Upper Saco Valley Land Trust, a North Conway-based organization that aims to protect land from development. The work seemed like a good way to use her environmental law expertise to give back to the village; Wright served on the development committee and then took a part-time administrative position. When the land trust received several grants to support regional food-system projects, the leadership team used the funds to offer Wright a full-time position as a local food systems advocate, which she enthusiastically accepted.

“I work with family-scale farms to make sure that farming is a viable enterprise here,” Wright says. She leads collective efforts to help farmers market their products, creating and maintaining directories that allow customers to find local food, and working to promote area farmers markets. Wright feels lucky to spend her days visiting local farms, checking out greenhouses, fields, and farm animals. “That’s what I’m working for, to make sure that these people can keep doing what they’re so passionate about,” she says.

Photo: Greta Rybus

Jessica Wright works for the Upper Saco Valley Land Trust.

But Wright’s choice to live in North Conway also involves some sacrifice. Because it’s a tourist area, housing can be expensive. At the same time, salaries typically lag behind those in cities, so Wright holds a second job as a bartender to help pay her student loans and mortgage. Also, few other permanent residents are in their 20s or early 30s. “People who might want to put down roots are delaying that until they’re 35 or 40,” Wright says. “They work on their careers in Boston or Portland or Portsmouth and wait until they have a better handle on their finances to come back and raise their families.”

Hoping to find solutions, Wright is chair of a group known as STAY MWV, for Supporting the Active Young Professionals of the Mount Washington Valley. In 2016, the group established a student debt scholarship that helps pay recipients’ loans for up to a year. “We’ve had so many discussions about the apparent lack of young people and examined the barriers to living up here,” she says. “If we could alleviate student debt for someone for one year, think how much more engaged they could be in their community. They could leave that second job and coach soccer or save for a house.”

Wright plans to continue her efforts to convince young adults to commit to North Conway. “The best thing about the work I do is knowing I’m benefiting the community that helped raise me, that’s helping raise a whole new generation of children, and where I’ll hopefully raise my own children one day,” she says. “That’s so rewarding.”

]]>At the same time, people in some parts of the world have limited or no access to energy due to poor or nonexistent infrastructure. The International Energy Agency reports that 1.2 billion people around the world live without power.

Meeting the world’s energy demands is complicated at best, difficult or improbable at worst. Alumni working in the industry talk about how energy sources, from gas and nuclear to solar and wind, are powering the world today, and what the future may hold for these industries and the people who depend on them.

JIM JUDGE ’77, MBA’81

CEO, Eversource

Jim Judge is a 40-year veteran of the power company now known as Eversource, which delivers electricity and gas to 3.7 million customers in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. During his career, Judge has watched New England’s energy industry shift to a reliance on natural gas. In 2000, natural gas generators made up just 15 percent of the region’s power plants, he recalls. But the development of mining techniques such as hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”) has created an abundance of cheap natural gas, so gas-fired plants in New England now exceed 50 percent of the total energy supply, with virtually all generators built during the past 20 years running on natural gas. Because natural gas releases less carbon than other fossil fuels, it is a preferred fuel source from an environmental perspective, Judge explains.

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Jim Judge ’77, MBA’81, CEO of Eversource, which delivers electricity and gas to customers in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire

Judge began his career as an associate rate analyst in 1977 at Boston Edison. Through the years, the company merged with other utilities to eventually become Eversource, and Judge rose through the ranks to become CEO last May. During those four decades, the world has developed a host of new uses for electricity, but energy demand has remained largely stable due to such factors as advances in the design of electronics and power plants. “New England’s generators are the newest and most efficient plants that we have on the system,” Judge says. The company also offers programs for improving energy efficiency to its customers. “We spend more than half a billion dollars a year on energy efficiency, so new buildings going up now use a fraction of the energy used, say, 30 years ago,” he explains.

Nonetheless, New England sometimes still struggles to get enough natural gas during peak periods, Judge says. To expand the region’s infrastructure, Eversource is part of a project known as Access Northeast, which seeks to update existing pipelines to bring more natural gas from the rich shale deposits in Pennsylvania into New England.

Judge notes that the energy industry also has grown “greener,” particularly in states such as Massachusetts where customers and policymakers continue to push for energy from renewables, including solar. “We are working closely with policymakers to help achieve aggressive carbon reduction goals,” he says.

Judge expects renewables to become increasingly important and believes Eversource is well positioned for that shift. The company currently is working on what he humorously describes as “a large extension cord up to Canada” to take advantage of excess energy produced by the country’s hydroelectric dams. Eversource also partnered with a Danish company that specializes in offshore wind power, and it has invested $200 million in a large-scale solar farm in Massachusetts. For now, renewables provide a relatively small part of the total supply needed, Judge acknowledges, due in part to a lack of affordable ways to store power once it’s generated. “As you know, the wind doesn’t always blow, the sun doesn’t always shine,” he says.

The big breakthrough will come when the industry develops batteries and other cost-effective methods to capture excess energy supply for later use. To that end, Eversource has launched a $100 million program to test energy storage technologies for five years, and it currently is considering projects located around Massachusetts. “It’s a significant investment, but we think this is the next major breakthrough for our industry,” Judge says, “and we’d like to lead the charge on it.”

ABHIJIT GUPTA, MBA’13

Founder, ACI Clean Energy

Following the completion of his MBA, Abhijit Gupta returned home to Mumbai, India, to launch a new branch of his family’s business: After decades in the IT industry, the company diversified into renewable energy. “India is the fastest-growing large economy in the world,” Gupta says. “There’s been a worldwide push for much cleaner fuel and renewable technologies, especially in the developing world, so we felt the demand would be there. It’s also a good area to be in from a moral standpoint, because I think we’re adding value to society.”

ACI Clean Energy provides biofuel made from wood scraps. It collects wood waste and sawdust generated by saw mills and other wood-processing industries and compresses them into pellets that can be burned as heating fuel. Although somewhat new in India, wood biofuels have a longer history in Europe, Gupta notes, driven in part by the requirement that 20 percent of the European Union energy needs be fulfilled by renewables by 2020.

For some ACI clients, such as large commercial kitchens that typically cook with propane, the change to biofuels can save money. For other clients, such as PepsiCo India, biofuel is more expensive than conventional fuels, notes Gupta. But PepsiCo chooses to use the pricier pellets in certain processes to raise its sustainability profile.

Gupta recently expanded ACI Clean Energy into designing, constructing, and maintaining solar installations. The company’s first project, completed in late 2016, involved installing a 400-kilowatt solar plant on a client’s factory roof. By the end of 2017, Gupta aims to install at least 10 megawatts of rooftop solar power, and he sees huge potential for future growth, given that India’s leadership has set aggressive goals for clean energy. “There is a government target for the country to install 100 gigawatts of solar power by 2022,” Gupta explains. “We’re at nine gigawatts now. That’s obviously massive growth, and billions of dollars of possible business.”

The World Bank reports that about 300 million people in India lack access to electricity. Utility companies are slowly building power lines to connect rural communities, but Gupta sees solar as a key solution, particularly if energy-storage technology improves, because solar lets consumers provide their own power. “It’s a fantastic solution for a country like India that needs more grid transmission connectivity,” he says. Even in countries like the U.S., the ability to store solar power will increase its popularity, Gupta believes. “That will be feasible in the future for sure,” he says.

JOHN CHAIMANIS, MBA’07

Co-founder, Kendall Sustainable Infrastructure; adjunct instructor, Babson

After volunteering as a teacher in an inner-city school and co-founding a public charter school in Boston, John Chaimanis was about to begin his MBA at Babson when he read an article about renewable energy in National Geographic. It included a photo that showed more than 70 people standing shoulder to shoulder before a massive wind turbine blade. The image “just blew my mind,” says Chaimanis, who from that point determined he wanted to work in the industry. Major European banks were backing wind projects, he notes, which encouraged his decision. “Once banks start putting hundreds of millions and billions of dollars into an industry,” Chaimanis says, “you have to believe it’s real, and not something that’s going to fade away tomorrow.”

With his goal in mind, Chaimanis started classes and relaunched Babson’s Energy and Environment Club, which had languished but came back to hold its first annual conference on energy topics that year. (Chaimanis remains involved in the club today as an alumni member.) After graduation, he joined Edison Mission Energy, an independent power producer, where he was part of a group that developed roughly 1,500 megawatts of wind projects in four years.

Chaimanis sees renewables as a savvy investment, but historically investors have had few ways to benefit directly. So Chaimanis partnered with Ken Lehman at Kendall Investments to create an offshoot company, Kendall Sustainable Infrastructure (KSI), which offers investments in closed-end funds focused on renewable energy projects. Chaimanis explains: “In a typical investment, our fund would spend about $1 million to build a solar asset, similar to a commercial real estate building, and then sell the power we produce, distributing that cash to investors.”

Through its funds, KSI owns interests in more than 30 projects around the country, mainly in solar power, although the company also considers investments in other renewables such as wind and hydropower. Chaimanis made the switch to solar around 2012, when wind power was well-established and he saw more potential for growth in distributed solar projects, the medium-sized installations that are bigger than rooftop panels but much smaller than utility-scale solar farms. The solar market has exploded; according to the Solar Energy Industries Association, solar experienced a compound annual growth rate of more than 60 percent during the past decade. Part of the appeal is that the installation cost has dropped, from $4 to $6 per installed watt five years ago to less than $2 a watt today, Chaimanis claims. “And it’s continuing to get cheaper and more competitive.”

He sees significant growth of renewables in other countries, including China and Mexico, which are aggressively investing in solar and wind power. “The recipe for successful renewable energy,” Chaimanis says, “is a stable regulatory climate with political certainty, and then the capital will come.”

Chaimanis acknowledges that renewable energy alone cannot yet supply all of the power needs in the U.S. “There’s more than enough wind energy and solar energy and land in the United States to generate the power we need,” Chaimanis says, “but the cost of storage today would make it an expensive proposition.”

However, Chaimanis sees a lot of work happening to increase the amount of renewables that the power grid can handle and to make the grid smarter and more efficient. Given the research by companies such as Tesla to develop cheaper battery technologies, he predicts the price of energy storage will become more affordable over the next decade. In the next 50 to 100 years, Chaimanis says, an all-renewable energy grid is “extremely possible.”

HUNTER HILL ’02

CFO, LPR Energy

Hunter Hill was born into an oil and gas family. Starting in the fifth grade, he spent summers working for his grandfather’s company, Hill Energy, helping map its oil and gas wells in Texas and Oklahoma. Later, when he graduated from Babson, Hill didn’t intend to join the family business. “But we were entering another energy boom, and my grandfather was getting up there in years and had failing health,” he says, “so I helped him run the company and wind down his affairs.”

After his grandfather’s death, Hill established PAS Capital, which invested in gas and oil projects. Later, he teamed up with his father and brothers to launch LPR Energy, a small, private oil and gas firm where he serves as CFO. The company drills for natural gas in central Pennsylvania; its customers include South Jersey Industries, one of the largest natural gas marketers in the Northeast.

Hill has had a front-row seat for the dramatic emergence of natural gas. In the early 2000s, companies working in the north-central Texas area perfected the then-new techniques of horizontal drilling and fracking to extract natural gas from a rock formation known as the Barnett Shale. The process involves drilling down at least a mile, and then drilling horizontally for several thousand feet through the shale. Once the well is drilled, water is pumped in, along with sand and additives, to create tiny fractures in the rock, permitting gas to escape. “One horizontal well can produce as much gas as probably 50 vertical wells,” Hill says, “but the cost of the horizontal well is only about three times that of one vertical well.”

Around 2008, companies including LPR began drilling in the Marcellus Shale, which includes areas in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and West Virginia, and found an abundance of natural gas. “In 2004, no one thought you’d be able to produce anything cost effectively from the Marcellus Shale, and today the Marcellus alone is producing 18 BCF [billion cubic feet] per day,” Hill says. “Overall production in the U.S. is around 70 BCF. The Marcellus is about 25 percent of production, and no one would have predicted that.” Hill says this has created jobs in the region, including at his own company, which employs more than 20 people to run its operations in central Pennsylvania.

The sudden abundance of natural gas triggered a dramatic drop in prices. “The oil and gas markets are very efficient, and the moment you have one molecule of excess supply, prices drop,” Hill explains. Still, given the current popularity of natural gas, he expects its price to increase in the near future. In addition to LPR Energy, Hill launched another company to purchase mineral rights from property owners in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. The company buys the minerals located under a person’s property, which gives Hill the right to lease the minerals for drilling, either by his company or a third party. If natural gas prices do rise, Hill’s company will drill new wells in search of additional gas.

Hill says one of the biggest challenges in natural gas is the question of what to do with the large quantities of wastewater produced by fracking; transporting the used water to disposal sites is one of LPR’s largest expenses. The challenge—and opportunity—lies in figuring out a portable, small-scale process to handle the water produced at the shale wells, cleaning it on-site for other uses, he says. Hill notes that people are working on this question; for the past five years, he has served as a judge for the Ben Franklin Technology Partners Shale Gas Innovation Contest, in which contestants pitch new ways to deal with mining challenges, including wastewater.

“There’s never a dull moment in this field,” Hill says. “You have to constantly be out there trying to figure out the next trend, the next game changer, and thinking, how is that going to impact my costs?”

ILENE MASON, MBA’08

Founder, Rethinking Power Management

Ilene Mason’s company, Rethinking Power Management (RPM), gives her insights into how municipalities and other organizations in New England are striving to become more sustainable, including their efforts to reduce power consumption.

Mason, who founded RPM to help organizations tackle sustainability issues and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, notes that New England is an especially exciting place to work on changing the local energy landscape. She cites former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick as a leader in this area for setting aggressive targets for carbon reductions and establishing a legislative framework to support those goals. Her small company has guided municipalities and businesses as they change their energy habits, from converting to LED streetlights to revamping the mechanical and ventilation systems in buildings. But meeting aggressive energy goals requires more than incremental changes, Mason adds. “If we’re going to achieve those carbon reductions, we need to go beyond changing lightbulbs and think more systemically, much more holistically, in terms of how we operate,” she says.

Mason admires innovative efforts by cities and towns to reduce their carbon emissions. “Boston and Cambridge have been very forward thinking in trying to reach those targets,” Mason says. She points to a “green steam” project, which involves a gas-fired power plant in Cambridge: The steam given off by the plant is captured and then routed by pipes to heat 250 buildings in Cambridge and Boston. Mason predicts that the energy infrastructure of the future will include more of these novel projects.

A metallurgical engineer by training, Mason took a break from that career when her children were young, volunteering for the Sierra Club and chairing her town’s recycling efforts. She eventually took a job with the Consortium for Energy Efficiency, which gave her insight into energy efficiency policies in the U.S. and Canada. But, as she finished her MBA at Babson, Mason realized she craved a role that would have a direct impact on energy use and greenhouse gas mitigation, and in 2009 she founded RPM.

Mason is concerned about what the current political climate could mean for energy efficiency and carbon-reduction efforts. “But I’m hopeful that local governments will be able to continue to push forward these kinds of policies and initiatives and continue to support them,” she says. “For me, the main driver is environmental stewardship, but the second piece of that is financial. As you become more efficient, you also can bring down costs, and for cities or towns or companies, that’s critical.”

CARL PEREZ ’15

Co-founder and CEO of Elysium Industries

Carl Perez and his co-founders at Elysium Industries want to build a better nuclear reactor. Their design is based on 1950s technology that was originally developed to power U.S. military planes, says Perez. The project was ultimately abandoned, due in part to budget cuts, and plans for this once-classified technology eventually were released into the public domain. Elysium obtained the plans, hired a staff of veteran nuclear designers, and is working to build a next-generation nuclear reactor that its founders view as a cheaper, carbon-free alternative to gas- and coal-fired power plants.

The Elysium team knows that the words “nuclear power” trigger fear of accidents like those in Chernobyl and Fukushima. But Perez says Elysium’s technology is safer and more stable than existing nuclear reactors because it uses a molten salt reactor, which doesn’t require human intervention to shut down in emergencies, such as a rise in temperature or an earthquake. And while older reactors burn roughly 4 percent of their uranium, the molten salt reactor burns 99.99 percent, eliminating the problems created by spent nuclear fuel, Perez explains. In fact, he claims this technology can run on the spent nuclear fuel generated by older nuclear plants.

Nuclear provides plentiful, carbon-free energy, says Perez, who believes that renewables such as wind and solar alone can’t meet the world’s voracious energy demands. For example, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reports that renewable energy provided only 13 percent of U.S. electricity in 2015. The Elysium reactor would produce about 1,000 megawatts of power, enough for 500,000 households in an industrialized country or more than 1 million households in less developed nations.

On a more personal level, one of Perez’s primary concerns is “energy poverty,” a lack of access to consistent power in Africa and elsewhere. The problem resonates for Perez, whose father was born in Algeria. During college, Perez studied such topics as the international energy infrastructure and the sub-Saharan energy sector. He found that though African countries are fertile for entrepreneurship, frequent power failures mean business owners must devote significant resources to purchasing backup power generators. Even developed areas in South Africa experience regular power outages, which limit the ability to conduct business. Perez wants to help and sees nuclear power as a solution.

For now, Elysium’s design team is about to begin materials testing on its first reactor. Although the company is pursuing the U.S. market, obtaining U.S. licenses is likely to take more than a decade. In the meantime, Perez and his colleagues are working with regulators in Canada, which has a vendor design review program that will take about three years. Elysium hopes interested utilities will sign on and then oversee licensing procedures and costs themselves. The company also hopes to attract interest in Japan. Perez says that in the aftermath of Fukushima, the country is dismantling its aging nuclear power plants, thus increasing its reliance on imported fossil fuels, so it is eager for safer nuclear options.

Given that renewable energy is unlikely to meet all of the world’s power needs in the foreseeable future, Elysium hopes to shift society’s thinking about nuclear power. “If the desired outcome is to generate electricity safely and without any carbon emissions,” Perez says, “then nuclear needs to be part of that discussion.”

SAVITHA SRIDHARAN, MBA’14

Founder and CEO, Orora Global

Photo: Jillian Clark

Savitha Sridharan, MBA’14, founder and CEO of Orora Global, provider of clean-energy solutions for rural and semi-urban communities

Savitha Sridharan believes that solar energy has the power to change women’s lives. Her company provides reliable and affordable renewable energy to rural communities in India that lack access to electricity; recent statistics from the World Bank reveal that about 300 million people in India don’t have power. She chose to focus on solar because it’s easily scalable and people in India seem open to this technology. “One of Orora’s chief missions is to empower more women to become part of the clean energy industry,” Sridharan says. “We hire and train women to become part of our network, and they go and light up the communities where they live in rural India.”

Born in Bangalore, Sridharan came to the U.S. to advance her studies, eventually working here for nine years as a designer of integrated circuits. “As much as life as an engineer was fun and I was doing what I wanted to do, I also had a strong passion for social change, for giving back to my country,” Sridharan says. Living in the U.S. with her husband, she raised thousands of dollars for nonprofits in India by running races, from 10ks to ultramarathons. A survivor of childhood sexual abuse, Sridharan felt especially committed to making life better for women.

At Babson, she focused on renewable energy, joining the Energy and Environment Club. “It gave me that confidence to go explore New England-based renewable companies, to learn about the industry and think about ways to replicate it or try something new,” she says. The concept for Orora took shape around two main products: solar-powered lanterns that hold a charge for up to eight hours after sitting in the sun for four to six hours, and solar-powered home-lighting systems. The company now also offers custom-built, solar-based systems for community buildings such as schools and hospitals.

Rural women tell Sridharan that her lanterns have been game changers. “If women don’t have sanitation, they have to walk into the wild to use the restroom at night,” Sridharan says. “They get attacked every day. My first customer made me cry. She said, ‘By giving me your solar lantern, I have not had a man touch me in three months, and I can walk around in the night safely.’ It’s returning their dignity, and that’s important to me.”

Orora is a for-profit company, and its main customers are local nonprofit agencies that connect Orora with communities. Orora helps the nonprofits raise funds to purchase lanterns and lighting systems for women to sell, and it trains women in salesmanship and business skills. “The women are involved in many ways, from business development to training other women to installing and servicing products to talking to the government,” Sridharan says. She recently teamed up with Womentum, a crowdfunding company founded by Babson undergraduate Prabha Dublish ’18, to run a yearlong campaign for Orora. They hope to raise enough in 2017 to give 200 women $150 each to start selling solar lanterns.

One of the beauties of solar power in rural India is its simplicity, Sridharan says. “Solar is one of the easiest solutions, because apart from the solar panels, all you need is the sun,” she says. “There’s no question of availability. In India, the sun is always there.”

Erin O’Donnell is a writer in Milwaukee.

]]>When looking for suppliers, Rogers considers not only the quality and cost of products, but also how well those operations treat the environment and their employees, requirements that align with his personal beliefs in protecting the environment and promoting social justice. “It’s the ultimate commitment to values in business. It’s baked into everything that Whole Foods does,” Rogers says. “We can use the power of business to reward people for the work they do. I get to do that every day.”

Rogers enjoys working for a company with a conscious mission. As a youth, he wasn’t sure such a career would be possible. In high school, he wanted to be an environmentalist, but his father questioned how Rogers could turn that interest into a career. “My dad, who was always supportive but not one to let you get away with anything, said, ‘Well, that’s wonderful, but not necessarily a job. Do you want to be an environmental lawyer, a scientist, an activist?’” says Rogers, who at the time wasn’t excited about any of those options. “Working for a business wasn’t on the list of things to do for someone with my interests.”

Rogers came to learn about such opportunities after graduating from Villanova University in 1997 and taking a job with what was then the New Jersey Office of Sustainable Business. The nascent office, created by Gov. Christine Todd Whitman, helped craft policy recommendations in support of sustainable businesses, as well as locate and expand green businesses in the state. “The idea of sustainable business was a new concept at the time,” Rogers says. “I was exposed to businesses that were doing cool and innovative things, making a difference through the power of business, whether with an environmental product or service or through recycling or energy conservation or organic farming.”

After working for several years in the office, Rogers decided that instead of being the person who helped these companies, he wanted to work at a sustainable company. He also wanted to move to the Boston area. Researching options, he discovered Preserve, which makes reusable and recyclable household products from recycled materials. Founded by Eric Hudson, MBA’92, the company is based outside of Boston in Waltham. “I called up Eric and begged my way into a job,” says Rogers.

Initially, Rogers took a part-time sales position, and in time he became Preserve’s national sales manager. “It was a very formative time for the company. I was involved with all aspects of the business,” Rogers says. Developing partnerships with companies such as Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s, which sell Preserve’s products, Rogers was introduced to the natural foods industry. He also learned about Babson through conversations with Hudson. “I realized that if I wanted to take my career to the next step, I needed some business fundamentals,” Rogers says. So after three years with Preserve, he left to earn his MBA.

But Rogers soon returned to the natural foods industry, taking an unusual job with Whole Foods in the fall after graduating. He became the business development coordinator for Earth University in Costa Rica, a position underwritten by Whole Foods. The job came about after Whole Foods executives learned of Earth University and reached out to see how the two could help each other, says Rogers. “Earth University teaches sustainable agriculture,” Rogers says, “but it also teaches entrepreneurship and business.” As part of its program, the school runs farms that grow a variety of produce. Whole Foods executives had a suggestion. “They said, ‘Why don’t you walk the talk and sell us your products. Sell us your products, and you’ll make money, and we’ll sell them,’” says Rogers.

Unfortunately, the arrangement wasn’t working very well. In addition to cultural and language challenges, says Rogers, Earth University had difficulty meeting Whole Foods’ stringent criteria for suppliers. “They’d be like, ‘We have 10 of these, the cost is $15 each, and we have them this one time.’ And Whole Foods would say, ‘That’s nice, but we need 1,000, and they need to cost $5, and we need to have them every week,’” Rogers says. Whole Foods realized that if it wanted the relationship to work, it had to hire someone to help the school, so it financed a business development position and support staff for three years. Rogers spotted the opening on Whole Foods’ website, applied, and got the job.

Photo: Winni Wintermeyer

Matt Rogers, MBA’05, at Jacobs Farm / Del Cabo

“It was a fantastic opportunity,” he says. “I used all my Babson skills, basically creating a business from scratch.” Rogers focused the business mainly on bananas, figuring out such logistics as how to get the fruit on a boat, how to make sure it was still fresh when imported, and how to get it on trucks and to Whole Foods distribution centers in good condition. “Whole Foods took a risk working with them,” Rogers says. “But many years later, we have bought millions of boxes of bananas from Earth University. We buy almost all of their production from an on-campus banana farm, where they do sustainability research to reduce the environmental impact of farming. And the profits from sales go to scholarships.”

Although he had a great experience at Earth University, Rogers was ready to come back to the States when his contract ended. “I was living in very rural Costa Rica, so the walls were closing in a little bit,” he says. When he told Whole Foods executives of his plans to move on, they offered him a job in their Watsonville, California, office, the company’s main location for produce procurement. “Whole Foods is a truly mission-driven organization,” Rogers says. “It was not a very difficult decision to work for them.”

During his time in the Watsonville office, Rogers has helped develop and implement the Whole Trade Guarantee and Responsibly Grown programs, which address a range of issues aimed at educating consumers about products and ensuring product quality while supporting suppliers, workers, and the environment. The work has been complicated, Rogers says, but satisfying. “We’re consistently dedicated to understanding the food supply,” he says, “and figuring out ways to drive things forward.”

The company’s desire for continuous improvement and long-term dedication to making a positive impact align closely with Rogers’ beliefs. He likes how Whole Foods’ values and mission are built into its business model, saying this frees employees to focus on their jobs. “Whole Foods is very competitive. It is exciting and a fun part of what we do. We want to win, because our success means success for the mission,” Rogers says. “It’s not always part of our daily conversation. It’s just part of who we are.”

Photo: Oliver Parini

Amy Levine, MBA’01, director of marketing, Cabot Creamery Cooperative, at its visitor’s center in Cabot, Vermont

From Nonprofit to For-Profit

As an undergraduate at Skidmore College, Amy Levine, MBA’01, was curious about how and why government policies are implemented, so she studied government to understand how things get done and psychology to explore why people do what they do. After graduating in 1993, she moved to Washington, D.C., and worked for a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization called the Center for Public Integrity, which investigates and reports on corruption at public and private institutions. “It’s bigger now, but at the time I was the fourth employee,” says Levine. “We were looking into the flow of money and politics and how legislation is informed and enforced.”

Being part of a small, grass-roots organization also taught Levine about entrepreneurship, as she worked on everything from investigating organizations to figuring out how to keep the doors open to copying press releases the night before a press conference. She enjoyed the work but soon found it took a toll on her emotions. “I was seeing all the ways in which our country doesn’t work and all the ways in which money leads to decisions—and not necessarily what’s best for the country,” she says. “So I thought, I don’t know if I can do this day in and day out. We were shedding light on important things, but I felt like I needed to have a more positive direct impact.”

She began volunteering on weekends with the Alternatives to Violence Project, which offers workshops on personal growth and conflict management to prisoners, communities, and youths. “I was going into maximum security prisons and teaching inmates about conflict resolution and anger management, but I was energized by working with people,” Levine says. “It made me look at people in a different way, making me realize that in some ways we’re all just one bad decision away from lives that would be very different.”

Through that organization, Levine began volunteering with high school students in D.C. as well. Then, in 1996, a friend told her about a job in Ithaca, New York, serving as a mediator for students in trouble and teaching them anger management skills. She moved and took a job with the not-for-profit Community Dispute Resolution Center (CDRC), where she worked mostly with middle and high school students. “I was loving the work I was doing, but getting frustrated with the system around nonprofits,” she says. “The nonprofits in this community were fighting for a limited number of funds, and this was creating an atmosphere of competition instead of collaboration.”

Thinking there must be a better way to have a positive impact, Levine started reading about companies that are making money but also doing social good. “I realized that if I wanted to make a difference, I needed to learn about business,” she says. So after three years with the CDRC, she left to earn her MBA, coming to Babson because she liked its focus on collaboration and entrepreneurship.

After graduating, Levine moved to Vermont with her husband, who had taken a teaching job in the state, and applied for a marketing position at Cabot Creamery Cooperative. More than 1,100 dairy farms in New York and New England are part of Cabot, which is known for its cheese and dairy products. Soon after arriving in Vermont, Levine was offered the job. More than 15 years later, she is still with the organization. “Previously, I hadn’t been anywhere more than three years,” she says. “Cabot is a great fit for me. I love being grounded in the environment and farming and keeping land open and maintaining that connection to the land. Farmers are the stewards of that. It’s a passion for me. It feels authentic.”

Working for a cooperative can be complicated at times, notes Levine. “Sometimes you want to do something for business reasons,” she says, “but it isn’t right for the farmers, so you don’t do it.” Because the goal of the cooperative is to return profits to the farmers, Levine also doesn’t receive a huge marketing budget like she might at another company. So she and her co-workers take a creative and entrepreneurial approach to spreading their message. Many of the Cabot farmers volunteer in their communities, so the marketing team created programs about engaging and thanking volunteers and encouraging participation. Cabot has a food truck called The Gratitude Grille, for example, that feeds volunteers at the sites where they are serving. Cabot also sponsors a cruise for people who have been outstanding contributors to their communities. “We bring 40 to 50 people on the cruise, and we host some seminars on best practices and volunteering. It’s a great way to bring like-minded people together,” Levine says.

Cabot is a B Corp as well, a certification handed out by the nonprofit organization B Lab, which makes its determination after examining a for-profit company’s social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency. “We’re part of a community that is saying we’re going to look at business as a force for good, and not just a way to meet the bottom line,” says Levine.

Collaborating with other B Corp companies has been exciting, says Levine. She is leading a steering committee of B Corp members who are examining how they work together and figuring out ways to grow the brand so that it becomes more recognizable to consumers. “The B Corp label will help consumers make a choice,” she says. “They can look at our product and say, ‘Oh, they’re a B Corp. I want that.’” Other initiatives at Cabot include belonging to the National Dairy FARM (Farmers Assuring Responsible Management) Program, which sets standards for animal care, and creating a group that addresses sustainability issues (Cabot recently won a U.S. Dairy Sustainability Award).

The challenging work at Cabot keeps Levine interested and busy. “I haven’t tired of it,” she says. Working for a company with a mission about which she feels passionate is important to her. “It’s always been about needing to be whole,” she says. “You don’t want your work life to feel separate from what goes on at home. When I entered the business workforce, I wanted to align my professional life with my true self.”

Levine believes more businesses need to realize that people increasingly want to choose jobs based not just on salary but on what a company stands for. “To attract talent, companies have to change the way they are. People don’t have to make a choice, either live a comfortable life or sacrifice and do good in the world,” she says. “They can align those values. It’s exciting.”

Spurred into Action

About eight years out of college, a book transformed the way John Moorhead, MBA’10, viewed his career. Moorhead grew up in New England, loving family, sports, and the outdoors. His main sport was lacrosse, which he played in high school and at Williams College, becoming captain of both teams and an All-American. During college, Moorhead also developed a greater appreciation for the outdoors, going on hikes in the nearby Berkshires of northwestern Massachusetts. “What a place that was to experience the outdoors and find ways to connect with the present moment,” he says. “It helped me to understand nature.”

Photo: Oliver Parini

John Moorhead, MBA’10, brand manager of e-commerce, Seventh Generation, at company headquarters in Burlington, Vermont

After graduating in 2000, Moorhead moved to Australia and worked for Coca-Cola during the Sydney Olympics. Taking the money he had earned, he then stretched his savings into almost a year of traveling the world, mostly to developing nations. “I had some hair-raising experiences,” he says, “but through my travels it became clear to me that I needed a lot more fundamental, real-life business training to understand the difference between what I was seeing in the U.S. and what I was seeing in these countries.” Upon returning to the States, he took an internship with Cat Partners, a hedge fund focused on small- and mid-cap companies; six months later, he was hired as a full-time analyst.

Fast forward five years, when Moorhead is engaged to be married and making a nice living. A college friend gave him the book Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution. “It was massively eye-opening, relating how much damage we’ve inflicted on the environment and those who can’t speak for themselves,” he says. “But it also detailed what we can do to help. Businesses can play a leadership role in helping people and the planet. Those things don’t have to be mutually exclusive. You can be profitable and mission oriented.”

At work, Moorhead delved deeper into his analyses of companies, examining how they conduct business as well as how they perform. He wanted to figure out how he could marry his personal and professional values, and he took notice of people who were starting to transform business practices: Gary Hirshberg of Stonyfield Farm and Ray Anderson of Interface, heads of corporations that built social responsibility and sustainability into their company models. “The deeper I got into it, the more clear it became that I could play a role,” he says.

At first, Moorhead tried to convince his firm to invest in the clean technology space. “They weren’t ready for that,” he says. “So it was time for me to go.” He talked with his fiancee (now wife) and decided to come to Babson to earn his MBA. “I fundamentally believe that entrepreneurship is the best way to drive systemic change,” he says, “so that’s why I chose Babson.”

While at Babson, Moorhead was president of the Energy and Environment Club, where he worked with the facilities team to bring single-stream recycling to campus and made connections in the sustainability industry. After graduating, he became director of business development for a startup called Banyan Environmental, which had developed a technology for capturing mercury emissions. “At Banyan, we were working all the time. My wife was six months pregnant,” he says. “The company didn’t succeed, but I learned more in that year about each of the operating functions of a business than ever before, and I figured out what I wanted for the next stage of my career. I realized that I loved brand management and marketing.”

From research and Babson connections, Moorhead also had a solid understanding of the sustainability industry. He decided to focus on companies in the consumer packaged goods sector, and Vermont-based Seventh Generation became his top choice. Founded more than 25 years ago, Seventh Generation formulates and sells plant-based cleaning and personal-care products aimed at improving the health and well-being of people and the environment. The company has social responsibility and sustainability built into its core business model and, like Cabot Creamery, is a B Corp. “Seventh Generation was one of the original companies to show that business can enter big markets for products that you use every day and do it in a better way,” Moorhead says. “I was elated to get an interview. It worked out very fast from there.”

Moorhead joined the marketing team and has worked on programs across the brand, most recently focusing on e-commerce. One of his responsibilities is to determine a revised strategy for Seventh Generation’s online shopping experience. “The online experience for a consumer is so different from their in-store experience. How do you make sure you understand this and address the needs of the consumer without driving up cost?” he says. “I developed an innovation agenda that I presented to the board in September. We’re resetting the way we think.”

Before tackling e-commerce, Moorhead focused on the baby business. During that time, one of his responsibilities was brand-building partnerships, and Moorhead helped connect Seventh Generation with Mamava, a developer of lactation suites that make breast-feeding in public places, such as airports, easier. Seventh Generation sponsored several suites. “We’re a business with a social mission, and we support moms. The deeper I got into the issue of how difficult it can be for women to find clean places to breast-feed when traveling, the more I realized it’s just a sad state,” Moorhead says. “I’m really proud of the inroads we made.”

Seventh Generation recently was purchased by giant consumer-goods company Unilever. Moorhead expects change but also believes that everyone, including the top executives at Unilever, is on board with preserving Seventh Generation’s core identity and mission. Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, has been recognized by industry observers for his efforts to make Unilever more sustainable and socially responsible. “Unilever will strengthen our ability to scale the business,” says Moorhead. “We need to appeal to more mission-oriented consumers. We also can do a better job of getting our products into the hands of people who can’t afford them. There are still lots of untapped opportunities for us.”

Moorhead believes in the future of companies like Seventh Generation. He knows being socially, environmentally, and financially responsible can be challenging, but that makes him more determined to succeed. “We can’t just come in to work and think about cost and performance. We have to think about the environment and personal health, too. We work really hard at it, from our research and design teams up through senior leadership,” he says. “But once you take a bite, you can’t go back. I’ve always been a passionate and purposeful person who is team oriented. Our mission is to inspire a consumer revolution that nurtures the health of the next generation. I have loved that process.”

Moorhead views Seventh Generation as a model for what businesses must do to continue to evolve. “Coming from an investment space and seeing as many companies as I have, I can tell you that the fastest and largest way to scale impact is a for-profit that stands for something,” he says. “Every time I go outdoors, I think about what I am going to leave for my kids. When they get older, I think they will really respect what we’re trying to do.”

]]>Today the couple produces tables in many styles, such as trestle, farm, Parsons, and bistro, as well as other pieces, including stools and bookcases, all custom-made from reclaimed and repurposed wood. “The hardest part is finding good wood,” says Whittier, who has traveled around rural Colorado to find stock. “It’s exciting,” he says. “You never know what you’re going to find in a barn until you break it down. The large rafters and trusses in some old barns were made from trees that sprouted around 500 years ago.”

The couple also has worked with tobacco-barn siding from rural Tennessee. Whittier says, “That wood, in all thicknesses and colors, from brown to silver, had taken on the aroma of tobacco. And we have found shotgun pellets in the wood.” Recently, Whittier’s favorite wood is cypress planks collected in Missouri, typically from barns and chicken coops. “This wood can have up to 100 to 150 years of use and paint,” he says. “You see hoof marks from horses, initials and dates scratched by kids, and worm holes.”

To craft each piece, the couple uses old-world techniques, such as mortise and tenon joints. Surfaces are cleaned with a wire brush and sanded, but not too much. “We may stain it,” says Whittier, “but the character remains.” To seal the wood and make the surface cleanable, pieces often are covered with a durable mix of oil and urethane. “Our tables are modern-day heirlooms,” says Whittier. “They’re made to be lived on and used; they’re built to withstand a hurricane.”

One of Whittier’s favorite projects was an emerald-green stained, 8-foot long by 3.5-foot wide dining table. “It was shocking and different,” he says, “but it looks terrific in the house. That’s the beauty of custom work. Truly anything is possible.” To learn more about Whittier’s creations, visit oldwoodsoul.com.

]]>The father of Susan Dacey, MBA’80, was one of those manufacturers, running a plant that developed and produced bomb fuses. In later years, though, Ralph Dacey grew dismayed as America’s manufacturing might slipped away. An industry that once produced an arsenal to free the world from oppression became replaced by a vast service economy. “We can’t all be shining each other’s shoes,” he would say.

Susan Dacey, now CEO of Industrial Polymers and Chemicals, the Shrewsbury, Mass.-based company that Ralph began in 1959, shares her dad’s sentiments. Her company makes a fiberglass reinforcement for abrasive cutting and grinding wheels. It is a tangible product, she says, and that’s what manufacturers provide.

Much has been said about the decline of American manufacturing. In 1990, manufacturing as a percentage of GDP stood at 16 percent. Two decades later, that percentage fell to about 11 percent. Consequently, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of Americans working in manufacturing dropped from 17.6 million to 11.5 million during that time. “Large-scale manufacturing has been declining for 25 years, and it’s unlikely to come back, at least not in the traditional form we know,” says Sebastian Fixson, assistant professor of technology and operations management.

When Americans think of the country’s golden age of manufacturing, they think of the auto plant job with union wages that enabled someone to buy a house, raise a family, and live a comfortable life. “We can no longer say there will be a nice job waiting for you on the assembly line,” says Kent Jones, professor of economics and the Kevern R. Joyce Term Chair. “We can’t replicate that. Trying to recapture the past isn’t going to work.” Recognize that today’s service economy isn’t a bad thing, Jones says. Think about the many people working in health care, education, and high-tech. Transitioning to an economy dominated by these types of jobs is the normal path that nations take as their citizens’ standard of living increases, Jones says.

Besides, everything isn’t doom and gloom in U.S. manufacturing. Despite overseas competition and the recession, manufacturers are finding ways to set up shop in the U.S. and make it work. They have found niches by making high-quality products, going green, focusing on local markets, or tapping into a growing demand for American-made items. They may not be massive companies employing thousands of people, but on a smaller scale, they’re proving that manufacturing is still a relevant part of the American landscape.

The Local Advantage

Depending on the industry, location can be a powerful asset for a manufacturer. Consider Bilco Brick in Lancaster, Texas. Thanks to the simple fact that its namesake product is heavy and expensive to move, Bilco enjoys a big local advantage. Ship bricks too far domestically, much less internationally, and a manufacturer soon eats into its profits. “The weight kills you,” says Randy Colen, MBA’86, Bilco’s president.

When Bilco’s machines are humming, the manufacturer’s 100,000-square-foot facility can crank out some 150 million bricks a year. Unfortunately, because of the recession and the toll it has taken on homebuilders—Bilco’s main customers—the company is producing only 24 million to 30 million bricks annually. “When all the pistons are running, the profit margins can be huge,” Colen says. “But when you’re not running on all pistons, the margins are terrible.” The 150-employee company, though, refuses to stand still and has diversified its business. Besides bricks, it now makes stone facade, steel products for leveling and fixing foundations, and green sand for golf courses. “I’m hanging on,” Colen says. “This is the worst economy in 70 years. You’ve got to be creative.”

Dacey’s Industrial Polymers and Chemicals also has a local leg up, being that its fiberglass products have a limited shelf life and are best used within three months. That puts its Chinese competitors at a disadvantage. “They have a hard time getting to market in a timely fashion,” she says. The cost savings from buying overseas are also disappearing. Ten years ago, if Industrial Polymers spent a dollar to manufacture an item, customers could buy the Chinese equivalent for just 30 cents. That figure has risen now to about 75 cents, which doesn’t include freight costs.

Still, manufacturing in America is challenging, says Dacey. “I have a hard time thinking of advantages,” she says. “Being close to market is one of the few.” Dacey cites the usual drawbacks: regulations, costly health insurance, relatively high wages. Like Bilco Brick, Industrial Polymers took a hit in the recession, suffering a 25 percent drop in sales between 2008 and 2009. Uneasiness about the future lingers. “I’m not hiring new people because I don’t know what’s going to happen,” Dacey says. Overall, though, business at the 60-employee company is good. “It was pretty bad, but we have come back,” she says. “It’s getting there.”

Mack Molding appreciates the significance of a local advantage. In the early 2000s, as many competitors migrated overseas, the supplier of contract manufacturing services and molded plastic parts developed a new business model, doubling down on its identity as an American manufacturer since 1920. “An honest look in the mirror resulted in two separate but connected strategies,” says Ray Burns ’74, president of Mack’s southern division.