Photo: Pat Piasecki; Score: Trevor Baca

The typical path to becoming a classical musician is as fixed as it is rigorous: With enough talent, effort, and luck, an aspiring musician earns a degree and lands an orchestra job. Jessi Rosinski, MBA’15, is a professional flutist who stepped off that path—and never looked back.

Rosinski says she picked up the flute as a child “on instinct and intuition,” drawn to the instrument’s direct, unmediated nature. “It’s truly an extension of the body. It’s really vocal and human; what you can do with your breath is what you can do with your flute,” Rosinski says. “It’s very organic, which makes it precious.”

Her ambitions evolved in college, when the aspiring classical musician realized that “contemporary music is where I really shine. Orchestra music doesn’t light me up the same way.” After graduation, instead of seeking an orchestra position, she went for a master’s degree, choosing the New England Conservatory (NEC) because of Boston’s burgeoning contemporary music scene. Today, Rosinski performs with several new-music ensembles, including the Callithumpian Consort, Boston Modern Orchestra Project, and Sound Icon; she also teaches entrepreneurial musicianship at NEC and does consulting for arts organizations.

Contemporary music, with its dissonance and complexity, can be a hard sell to some audiences, she acknowledges. But to Rosinski, new music has an urgency that makes it vital. “What drives me as a musician is bringing to life something exciting and relevant,” says Rosinski. “Contemporary music is here and now.” Playing newly written music, she says, also allows her to form collaborative relationships with composers. “I love working on new pieces and premieres. It’s awesome to help a composer bring a piece to life,” she says.

Her Babson degree—earned, she says, “to see if my voice could go beyond my instrument”—supports her ever-evolving goals. “Contemporary music and entrepreneurship are both about creating new things and finding ways to make the impossible possible,” she says. “They’re the same in so many ways.”

]]>

Photo: Justin Knight

From left, Steven Maler, director of the Sorenson Center, Richard Sorenson, MBA’68, P’97, ’00, Sandy Sorenson, P’97, ’00, and President Kerry Healey attended the February celebration.

In February, the Richard W. Sorenson Center for the Arts celebrated its 20th anniversary with a slate of performances that demonstrated the breadth and depth of Babson’s arts programming. The project that began as a suggestion has evolved into a vital campus resource, one that helps the College provide a well-rounded educational experience for students.

Photo: Justin Knight

A cappella group Rocket Pitches performed a lively version of Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition.”

Although the Center has played an important role since its inception, by all accounts its programming took a significant leap forward when President Kerry Healey hired Steven Maler to direct the Sorenson Center in 2013. Maler, a well-known figure in Boston theater circles, brought with him the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company, for which he serves as founding artistic director. CSC is now Babson’s theater company in residence, mounting several productions on campus each season as well as annual free Shakespeare performances on the Boston Common.

Photo: Justin Knight

Students Against Gravity played an improv game.

Maler is excited by the “pedagogical tie-ins” between the arts and the classroom that he has been able to find and create. He lauds the Sorensons’ “prescience” in helping bring the arts to campus some 20 years ago. “The requirements of creativity in the workforce now are so much more manifest and manifold than they were when the Sorensons gave this gift,” he says. “I think the Sorenson Center has become an urgent necessity in equipping our students to go out into the world.”

Photo: Justin Knight

Alex Markovitz ’10 (at the piano) and Jess Carvo, who perform as Satellite Mode, offered an original tune.

At the February showcase, the Babson community’s talents, from singing to dancing to performing improv and more, were very much in evidence among the 15 or so numbers. As a finale, CSC artist Anthony Rapp, who originated the role of Mark Cohen in Rent, joined students on stage to perform the anthemic “Seasons of Love.” Student artwork—paintings, drawings, ceramics—was on display in the lobby outside the theater, a reminder that the Sorenson Center supports visual as well as performing arts.

The Sorensons, who also fund scholarships for students involved in the arts, are frequently asked why a business school needs an arts program. In response, they tend to flip the question around. “Without the arts,” says Richard, “life would be pretty empty and stark. It’s such an integral part of human existence. Why shouldn’t every business school have an arts presence?”—Jane Dornbusch

]]>Since then, Kent has traveled many a mile and sung many a song. He plays his music, a warm, rollicking mix of country, rock, and folk, to audiences from coast to coast, performing 100 to 150 shows a year. Life on the road can be liberating, but it also can be repetitive and exhausting. Driving from one gig to another, he and his bandmates take three-hour shifts behind the wheel of an Econoline van, which is stuffed with gear. With no roadies to help them unload and set up before a show, they do it themselves, and when the concert is over, they load the van back up and hit the road again.

This grind, of packing and unpacking, of playing to strangers night after night, is traditionally how music careers are made. “If you want to do it full time, you have to hit the road,” says Kent. “That’s where you make money.” But as the digital age continues to upend the music industry, forever altering the way fans discover and listen to artists, many of the rules of the music game have changed. Hard work, undeniable songs, and a drive to play for people—these remain the basics of a successful life in music. But also needed nowadays, for not only singers on the stage but executives behind the scenes, is a nimble mindset, one that is comfortable navigating an industry in flux and open to exploring new opportunities.

Kent has done just that. Beyond extensive touring, he has started a small record label, has scored a couple of corporate partnerships, writes songs for a publishing company, organizes tours for other artists, and has brought together a dedicated group of fans, known as The Collective, that have provided him with funding and much-needed advice.

One thing he hasn’t done is sign a record deal, but his career is flourishing nonetheless. Kent’s last album, American Mutt, landed on Billboard’s top 20 country album chart when it was released in November. Kent heard the news while he was on tour, staying at a Holiday Inn in Tennessee. “I cracked open a great bottle of Scotch with my band,” he says. “It was a bottle I had been saving for a special occasion.”

Photo: Jason Myers

Kerry O’Neil, MBA’78, at the office of Big Yellow Dog Music in Nashville

The Door Is Open

One big conundrum has bedeviled the music industry for years: the internet. It allows for unparalleled access to music, but at the same time, making money off that access, or at least making the same sums of money as when the industry’s bread-and-butter was selling physical CDs, has proven elusive. As CDs and even music downloads continue their inexorable decline, the streaming of songs through subscription sites such as Spotify, Apple Music, and Google Play Music is increasingly the way fans hear music.

Kerry O’Neil, MBA’78, has witnessed these developments firsthand. He co-owns both a music business management firm, O’Neil Hagaman, and a music publishing company, Big Yellow Dog Music, that are based in Nashville. As he navigates the turbulent state of the industry, O’Neil adjusts and adapts. Gone are the days, for instance, when Big Yellow Dog Music would put together annual business plans. “Now, they’re not even quarterly. They’re just continuous,” O’Neil says. “Our style with dealing with change is saying, ‘The door is open.’”

O’Neil originally came to Nashville because he wanted to be a songwriter. He started writing songs in grade school, and as an undergraduate dropped out of college for a while because he was spending too much time on his songs rather than his studies. Arriving in Music City in 1980, he pursued songwriting during evenings and weekends while working at a CPA firm, where he built a client base of artists.

Surrounded by the city’s many amazing writers and artists, O’Neil came to two realizations. “The talent in Nashville, it’s the best in the world. What I found out was that I was just an OK writer,” he says. “It also became apparent that I had an ability to empathize with creative people. I understood their personalities.” So O’Neil drifted away from his dream of becoming a hit songwriter and embraced a career helping artists with their finances. His services were badly needed, as artists often entrusted their money to family members, many of them unqualified for the job. “People would get into all sorts of problems,” he says. “There were legendary IRS problems in Nashville back then.”

In 1984, O’Neil co-founded O’Neil Hagaman, and today it employs 50 people charged with handling the business side of music, whether merchandising, touring logistics, or record deal negotiations. “At any time, our artists have some of the top tours in the nation, some of the top albums,” says O’Neil, though he declines to mention any of his clients’ names. “We don’t as a rule do that. Their privacy is a primary goal.” The firm keeps a low profile and doesn’t even have a website. “We’re known as one of the quietest management companies,” he says.

O’Neil is more forthcoming about his work with Big Yellow Dog Music, which develops and promotes a group of 20 songwriters. Founded in 1998, the company has three main facets to its business, explains O’Neil. The first is traditional song publishing, in which Big Yellow Dog Music seeks artists to record its songwriters’ pieces. It also sets up songwriting sessions in which its writers compose with other artists. One of the company’s better-known writers is Meghan Trainor. While Trainor is a pop star on her own, having released the smash All About that Bass a few years back, she also has co-written hits for other artists, including Rascal Flatts and Jennifer Lopez.

Another department at Big Yellow Dog Music places its writers’ songs in TV shows, movies, and commercials. Over the past five years, 80 songs from the company’s writers have appeared in the TV show Nashville, while the films The Peanuts Movie and Smurfs: The Lost Village and TV shows Big Little Lies and Grey’s Anatomy also have featured Big Yellow Dog Music songs. With the instability in the music industry, these song placements represent a steady form of revenue and exposure for writers, says O’Neil. Last year, the company landed 400 song placements around the world.

The last facet of the organization’s business is artist development. Big Yellow Dog Music helps its artists grow their voices and build careers, a process that can take years. When signing a writer, the company is looking for people who have talent and something to say. It isn’t concerned with where their songs might fit in the everchanging marketplace. O’Neil compares the company’s thinking to that of a team in the NFL draft that picks a player for his talent, not necessarily for the position he will play. “The artists we work with, we try to find the ones who are so unique, people don’t know what to do with them,” he says.

For writers who also are performing artists, Big Yellow Dog Music looks to hone their sound. The company will bring artists and producers together, and it has its own record label, so it can record artists and put out their albums. To help them gain exposure through the variety of channels that music fans use to discover new music today, such as YouTube, social media, or streaming sites, the company tailors its approach to each individual. One of its artists, Jessie James Decker, used her strong social media following to propel downloads of her single, Lights Down Low. Another artist, Maren Morris, found great success on Spotify. “That doesn’t mean Spotify will break the next act,” O’Neil says. “Every artist is different. Every artist is on a different track.”

A Great Time for Artists

These many digital platforms are tools that musicians didn’t have a generation ago. “This is a great time to be an artist,” says Jon Ricci ’05, founder and lead singer of the hard-driving rock band Lansdowne. While streaming sites don’t pay high fees to most artists, Spotify and the like do allow them to release their music directly to consumers without the aid of a record company. A site such as TuneCore will distribute Lansdowne’s music to whatever digital platform Ricci chooses, and another site, SoundExchange, can collect his royalties. Lansdowne may have released two physical CDs in the past, but it has no intention of putting out more in the future, Ricci says, not when the band’s songs already have been streamed millions of times online. The digital age has changed the way music fans find new artists. They don’t have to go to a club, or turn on the radio, or even venture to one of the dwindling record stores. They simply can go online. “The discovery of new music has become frictionless,” says Ricci, who lives in Bolton, Massachusetts.

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Jon Ricci ’05 at the Brighton Music Hall in Boston

As a first-year student at Babson, Ricci didn’t intend to make music a career. His original plan was to become an investment banker. But he was inspired by his liberal arts courses, and he began singing and writing songs and spent many nights jamming in the rehearsal space in the basement of Park Manor Central. By the time he was set to graduate, the course of his life had changed. He was now an artist. “I wanted to give it a shot,” Ricci says. “I had to be true to what I was passionate about.”

Lansdowne formed in 2006, and its music has found a healthy audience. One of its more well-known songs, One Shot, has been viewed more than 4 million times on YouTube. The band has played well over 1,000 shows, including in the Middle East, where it entertained American troops. In Afghanistan, Ricci met a soldier who had the band’s name tattooed across his back.

Along the way, Lansdowne has taken a pass on not one, but two, potential record deals, as well as a slot on the TV show America’s Got Talent. At first glance, this may seem surprising, but Ricci says the terms of these opportunities weren’t right for the band. Because record companies no longer make as much money from music sales, they now seek additional sources of revenue with so-called 360 degree deals, which take a piece not only of a band’s music sales but also of its touring and merchandise earnings. That revenue is critical to a band’s survival, so the band decided to turn down the record deals.

As for America’s Got Talent, the show would have required that Lansdowne sign a long-term management deal that also took a piece of touring and merchandise sales. The price seemed too high for a TV appearance that would provide fleeting public attention. “It was hard to turn that stuff down,” Ricci admits. “I think it was the right call.”

Ricci isn’t opposed to signing a record deal in the future. A record company’s marketing muscle could prove critical given the right circumstances. And as the band continues to gain in popularity, it might be able to negotiate a deal with better terms. In the meantime, Lansdowne has three investors who provide the band with capital for making records and promotions. In return, the investors receive equity in the band or a piece of album profits, depending on the terms of their agreement.

Lansdowne should be back in the studio soon, ready to record a new batch of songs that Ricci has written. But the husband and father of two makes sure that life in a rock band doesn’t take precedence over his life at home. After missing his son’s first birthday because Lansdowne was playing a show, he vowed not to let that happen again. “You can’t miss those things,” he says. Lately, Ricci has kept busy with his venture, Prechorus, an app that centralizes the information needed to produce and promote a live event. Too often when bands play a venue, Ricci says, details about gear, lighting, promotional materials, and a host of other considerations can become lost in a slew of emails and written notes.

Prechorus puts all that nitty-gritty information in one central spot for easier access. Prechorus currently is being tested at two Boston-area venues, Brighton Music Hall and The Sinclair, and Ricci enjoys working on the startup, a much quieter pursuit compared to rock ’n’ roll. “I get as much out of building software as being on stage,” he says.

Photo: Jorge Oviedo

Camila Saravia ’04 in Bogota, Colombia

Plan for the Future

Offstage is where Camila Saravia ’04 operates. She is the CEO and co-founder of M3 Music, a management company working with Colombian bands. “There is a lot of talent in Colombia,” says Saravia, who lives and works in Bogota and also has an office in Miami.

While the growth of streaming has brought a somewhat steadier flow of revenue to record labels, Saravia says that innovative thinking is still in short supply. “People are very comfortable and not thinking in a more forward-thinking way,” she says. “If you are able to understand new opportunities, there are so many things to be done.”

M3 Music always is looking to the future with its clients. The firm sets specific career goals for them, something to which the more free-spirited musicians may not be accustomed. “We look at the artists not just as art, but also as a business,” Saravia says. “It’s been quite difficult to have musicians think that way.” M3 Music focuses a lot of its efforts on international strategy. If the goal is for a band to develop the U.S. market, for instance, M3 Music will set up a tour, or release a single and video, or book a date at a big festival and hope to land a primo time slot, one that isn’t too early in the day.

Saravia also works in music publishing, albeit with a tech twist. She is the cofounder and communications director of MusicAll, an online platform that connects companies, ad agencies, video-game producers, and others in need of music with a community of independent composers and artists. An ad agency that needs music for a commercial, for instance, can search MusicAll’s catalog of artists and songs. It also can request a custom-made song for the ad; if the agency wants an original up-tempo song with a Latin feel, a request is sent to MusicAll’s artists, who respond with ideas. Saravia says the site has proven popular with musicians. “There are so many independent artists,” she says. “It’s not easy for them to get their music heard.”

Saravia has always loved music. While at Babson, she was constantly attending concerts, typically about three a week, in Boston and New York City. Her mother recently found a scrapbook of her ticket stubs. “I can’t believe all the shows I saw,” Saravia says. Back home in Colombia after graduation, she worked for a producer of advertising jingles for a year and a half before heading to Barcelona, where she earned master’s degrees in both international marketing and the music business.

Returning again to Colombia, she became partner and vice president of a music management and promotion firm, SCP Music, which had a roster of 18 bands but only a small, harried staff. Saravia helped put on the bands’ concerts, which meant attending about 10 shows in an average weekend. “It was fun for a while in my 20s, but it was tiring,” she says. “That’s when I realized it was better to focus. Having so many bands wasn’t the way to go.” So in 2010 when she co-founded her own firm, M3 Music, Saravia decided to keep the roster small. Today M3 manages just four bands.

The most popular of those acts is Bomba Estereo, which tours all over the world and scored a catchy hit, Soy Yo, that is used in Samsung and Target ads. The song’s popularity was helped in large part by its fun video, which centers on an independent-minded girl intent on living life her own way. To create the video, M3 solicited ideas through a website called Genero, and a Danish director, who hadn’t even heard of the band, submitted the winning proposal.

When promoting a new song, M3 focuses not so much on radio as on social media. “Social media is important to us,” Saravia says. “It’s very effective. It’s very close to your fans.” For Soy Yo, M3 reached out to people popular on social media and asked them to post the video. The strategy worked. “After releasing the video, it was crazy,” Saravia says. “Everyone started posting it.” On YouTube, Soy Yo has been viewed more than 20 million times.

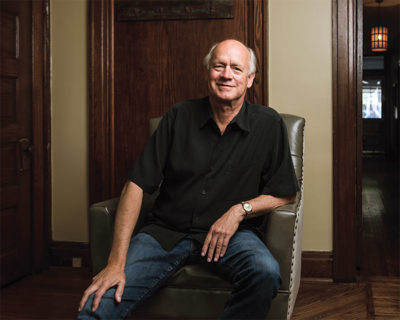

Road Warrior and Businessman

As much as social media and streaming are a great way to reach listeners, singer-songwriter Jamie Kent believes there is still no substitute for touring. Traveling repeatedly across the country, he may play a major market as many as four times in a year. Two of those appearances may be headlining shows, while the other two may be at festivals or as an opening act—gigs intended to expose him to a new audience. This summer, as he has done in the past, Kent and his band are opening on a number of dates for ’80s pop heroes Huey Lewis and the News.

Kent’s growing success as an artist can be measured by his choice of lodging while on tour. When he first started touring, Kent mainly slept on other people’s couches. Since then, he has graduated from couches to Motel 6, then to La Quinta, and now to Holiday Inn. “It’s a tangible level of growth,” he says. “Some bands love crashing on couches. I need my own bed at night.” He has yet to reach the ultimate symbol of success as a touring act: a bus. For now, Kent is content to be economical and travel in a van. “Money saved is money earned. Until you reach a certain level, you don’t need it,” he says. “I’ll run the numbers and see when it makes sense to get a bus.”

Kent believes so much in the importance of touring that he has partnered with First Note Play, an artist development agency. Together with First Note Play, Kent will develop tours for emerging artists. He envisions the tours as old-fashioned road shows, where several acts travel together, performing concerts but also doing community events such as school visits as they hit the same markets again and again to build a fan base. “A lot of artists don’t have the ability to book and promote a tour on their own,” Kent says. “This helps artists grow their own markets.”

Kent long has known that he wanted to make a living as a performer. He first picked up the guitar and started writing songs in high school. “I’m an only child,” he says. “On some fundamental level, I have to be the center of attention. That’s the Freudian diagnosis of my career.” When choosing colleges, Kent picked Babson over the Berklee College of Music because he wanted solid business skills, which so many artists lack.

He put those skills right to work. To fulfill a need for capital at the beginning of his career, Kent started a unique fan partnership he called The Collective. Fans provided Kent with monetary support and career advice, offering opinions on album artwork and which songs to push as singles. In exchange, Collective members received exclusive songs and free admission to shows. Eventually about 600 people signed up, and while Kent no longer asks for money from members, he continues to value their input. “My fans have a say in my career,” he says. “Data and insight from fans is more valuable than ever.”

Kent has formed other partnerships, landing Bose and Durango Boots as corporate sponsors. Kent receives sound equipment from Bose, boots and funding from Durango, and he plays events for both companies in return, showing off their products as he performs. “We’re evangelists for them,” he says. “I help promote their products in a cool way.”

Now he’s hoping to find a top-level manager, someone with strong industry connections who can “knock down doors.” Until then, Kent will continue to do what he always has done: work hard. When not on the road, he spends about 12 hours a day laboring on his career, whether booking shows, doing publicity, or writing songs for himself, other artists, or a publishing company that pitches his tunes to TV shows, films, and commercials.

Just like Jon Ricci of Lansdowne, Kent isn’t rushing into a record deal. Any such deal demands caution, for labels aren’t too forgiving of failure. “They will sink half a million dollars of promotion into a record, but if it doesn’t catch fire, that’s your chance,” Kent says. “I have spent too much time and effort building this thing to gamble it on one shot.” Ideally, he would like to sign a co-venture deal that partners the small record label that he started, Road Dog Records, with a major label. This would give him access to a label’s promotional arm and radio connections, though such a deal is still a ways off. “To do that, you’ve got to bring a lot of fans to the table,” he says. “We’ve got a lot of fans, but not to that level.”

Still, Kent has earned the right to be proud. He and his band are working musicians who have successfully grappled with the tumultuous times of a changing industry. “We’ve done some amazing things,” he says. “We’re making money, and we’re growing.”

Photo: Jason Myers

Jamie Kent ’09 in Nashville

Illustration: Neil Webb/theispot.com

To perfect one of the songs in their repertoire, the students in the Rocket Pitches a cappella group need about a month and a half of practice. In rehearsal after rehearsal, huddled together in a room in Sorenson, they seek the right blend of their voices. All the altos and sopranos, the tenors and basses, need to come together as one. When they reach that moment of unison, it’s hard to miss. “It gives me shivers,” says Judy Liu ’15, one of the group’s 20 singers.

To move people with their music is the goal of the Rocket Pitches. “We want the audience to feel the emotion,” Liu says. Founded about six years ago, their name an homage to one of Babson’s signature events, the Rocket Pitches sing at campus happenings and host an open mic night in Reynolds’ dining area. They perform songs such as Elton John’s Can You Feel the Love Tonight, Beyonce’s End of Time, and Seasons of Love from the musical Rent. “We do modern music,” says Liu, who serves as the group’s vice president for communications. “We feel everyone can relate to it.”

The music offers different rewards to the group’s members. “Music is a big part of my life,” says Sarah Noh ’16, the Rocket Pitches’ president. From elementary school through high school, Noh played the violin in orchestras, and she almost majored in music before changing her mind at the last minute. She joined the Rocket Pitches as a way to keep music and performance in her life. “I didn’t want to lose it,” she says.

For Liu, who always has loved singing, the group allows her to do something she has avoided: sing in front of others. “I think I’ve had a slight case of stage fright since I was young,” she says. “I want to overcome that fear.” Even if surrounded by others, though, she admits that performing onstage still isn’t easy. Singing without musical accompaniment can make one feel vulnerable at times. Make a mistake, and you break that wall of unified voices. “If one person is out of sync, you can hear it,” Liu says.

Beyond singing, the Rocket Pitches plan to change their act a bit this year. They’re adding more movement, some swaying, finger snaps, and steps, and they’re hoping to experiment with percussion. “We would like to have a beatboxer this year,” Liu says. “It would add more spunk.” But efforts to recruit a beatboxer, basically someone who uses his or her mouth and voice to make all sorts of rhythmic sounds, have proven unsuccessful so far.

Whether they find that person or not, the Rocket Pitches remain a tight group that stays in harmony both onstage and off. “This is where I made most of my close friends,” Noh says.—John Crawford

]]>

Photo: Webb Chappell

Sam Sternweiler ’17 (left) and Kai Haskins ’18

For Kai Haskins ’18 and Sam Sternweiler ’17, radio still holds an allure, a magic.

In an age when any kind of music you long to hear can be found on the Internet and sites like Pandora use algorithms to recommend songs, radio offers a personal and intimate experience, they believe. To turn on a station, to hear that voice come out of the speakers, is to invite someone into your life, say Haskins, the president of Babson College Radio, and Sternweiler, the station’s vice president for campus events. “The communal aspect of music still matters,” Haskins says. “Sharing your music with someone is a personal thing. It’s more fulfilling than when an algorithm recommends music.”

Babson College Radio has been heard online since 1998, and today it plays what Haskins describes as an “eclectic smorgasbord” of music. For years, the station made its home in Park Manor Central, but construction necessitated a relocation to Mandell Family Hall. Early in the semester, the station was still recovering from the move. Wires, microphone stands, a disco ball, and lots of records, given vinyl’s resurgence in recent years, were scattered about the studio. But the turntables already were set up and ready to go, and Haskins and Sternweiler were excited about the year ahead. Plans include a live 24-hour broadcast for charity, a show on entrepreneurship, and bringing more bands to campus.

About 30 students signed up to be disc jockeys, which is easily double the usual number. To get to know the new DJs, Haskins and Sternweiler asked them to turn in an eight-song playlist and to explain why they picked their songs and in what order the songs should run. “Order matters,” Haskins says.

The station is on air 24/7. Haskins and Sternweiler hope to have the DJs playing music 24 to 30 hours a week (when no one mans the studio, the station broadcasts a long, continuous playlist). To increase the station’s visibility, Sternweiler also DJs at one or two campus events every week. He loves seeing how the music he plays affects people, how it makes them sing and dance. “That’s a satisfying feeling,” he says.

To hear Babson College Radio, go to Trim Dining Hall, where the station is streamed throughout the day, or visit babsonradio.com. In a typical month, the site has about 3,000 listeners, though Sternweiler doesn’t care about the size of the audience. He takes to the microphone to share some of himself and his music. “The feeling that someone might be listening makes it all worthwhile,” he says.—John Crawford

]]>

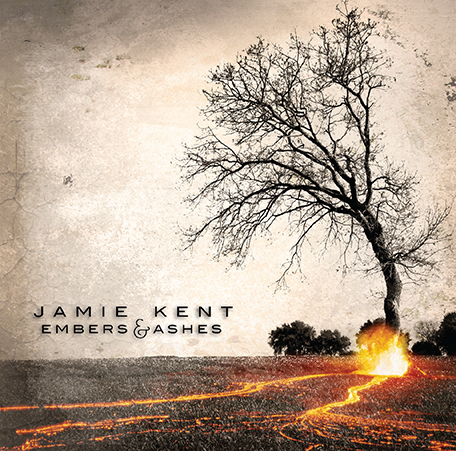

Cover Art: Kris Lyons

To date, Jamie Kent ’09, musician and songwriter, has released four albums. Two are full length, with 10 songs each, and two are shorter releases (EPs) with five songs, like his most recent, Embers & Ashes. Kent says, “Even if I had 10 tunes, I’d rather produce two EPs. It’s a shame, but everyone’s attention span, even that of record execs, is short now. It’s easier to keep people interested with an EP.”

Kent’s introduction to music came at an early age, when he was “forced,” as he says, into playing different instruments—violin, trumpet, cello, percussion—probably because his parents didn’t have that opportunity. “But all I wanted to play was sports.”

However, once he reached high school, Kent realized that the guys who played in bands got the girls’ attention, so he picked up the guitar. He quickly fell in love with music and started to compose songs. “I had all sorts of feelings I wanted to capture,” he says. “At first, I was focused more on music. Now I’m focused more on lyrics. As a songwriter, I’ve developed songwriter ears. I used to carry a small recorder for ideas and melodies, but now I have an app on my phone that takes care of that.”

Recently on a bus in Puerto Rico, Kent noticed a small restaurant called Rosalita’s Kitchen, and he had an aha moment. Feeling inspired, he sang loudly and passionately into his phone and says he probably freaked out everyone on the bus. That moment became Rosalita, a song for Kent and his group, The Options. “Art comes before embarrassment,” he says.

Kent also has been writing with other people. At first, he was resistant to the idea because he felt strong ownership for his emotions and ideas. “But collaboration blew my mind,” he says. “When it’s just you, it’s tough to have perspective. When you work with other people, they tend to challenge your ideas. The experience can be intense.”

Lately, his inspiration comes from time on the road and how it affects his friends, family, relationships, and himself. “A theme seems to be the journey—the constant work and struggle—of being a musician,” says Kent. “And some are love songs. Sometimes, I can’t resist.”

]]>

Photo: Tom Kates

David Oksman ‘03

Summertime means outdoor music festivals. In New England, one of the best for families has been organized by Life is good, creator of those T-shirts depicting a grinning stick figure named Jake, to support its 501(c)(3) charity. The Life is good Playmakers promotes healing among children who face traumatic life experiences, such as illness, violence, and poverty.

“Nothing connects people like music,” says David Oksman ’03, head of marketing for Life is good, which has evolved to sell apparel and other merchandise beyond the Jake designs. “Once you put music on, people are going to dance. They’re going to connect in that energy. It’s a really powerful way to bring people together.”

The two-day festival has featured artists such as Dave Matthews and The Roots on its main stage, while the Good Kids stage has hosted musicians such as The Fresh Beat Band and Laurie Berkner, favorites among the under-10 set (although many older folks enjoy these groups, too). Since 2010, Life is good has raised more than $11 million for the Playmakers program.

Philanthropy has been central to the brand from its beginning, Oksman notes. Company founders and brothers Bert and John Jacobs turned their events into fundraisers after receiving letters from customers who reported that Life is good T-shirts kept them focused and upbeat through difficult times, such as cancer treatments.

This year Life is good took a break from the two-day festival format to experiment with smaller events that continued the tradition of celebrating music and supporting kids. In July, it sponsored a night of the Soulshine tour, which featured Michael Franti & Spearhead (perhaps best known for the song Say Hey (I Love You)) along with other artists. Held at the Blue Hills Bank Pavilion, an outdoor amphitheater in Boston, the concert raised one dollar from every ticket sold for the foundation, and attendees could raise additional funds to receive special perks, including preferred seating and entry to a pre-concert party. The event had a minifestival vibe, with games and activities, including a pre-concert yoga class, for all ages and abilities, which was accompanied by Franti and others playing an acoustic session.

Oksman takes a lead role in orchestrating these events, ensuring that they mesh with the Life is good brand strategy and heading the team that handles marketing, social media, and logistics. As a bonus, he gets to meet top musicians. Oksman went to the Tennessee music festival Bonnaroo in June 2013 to announce that the singer-songwriter Jack Johnson would be headlining the Life is good festival later that summer. Johnson was at Bonnaroo to play a small set with friends, but when the band Mumford & Sons had to pull out of its headlining slot at the last minute, Johnson was asked if his band could fill in. Despite not having played a big show in more than a year, Johnson’s band came together and pulled it off. “He did so with a few hours practice and nailed an 80,000- person show,” Oksman remembers.

Afterward, Oksman spent some time with Johnson and his family. “They were the nicest people in the world,” he says. “He was everything you would imagine from a smart, philanthropic artist.” The icing on the cake? The next day, when Oksman and his team launched their 2013 festival marketing campaign, they received a publicity boost for their headliner from the music media, including Billboard and Rolling Stone, which was clamoring about how Johnson saved Bonnaroo.

Meeting celebrities has been fun, but the festival’s message is what resonates with Oksman. “The festival is the best weekend of the year, period,” he says. “Bringing together 30,000 optimists to focus on what’s right with the world always inspires me. I love seeing people of all ages enjoying the outdoor games and the great music, all while making the world a little bit stronger.”—Erin O’Donnell

(Editor’s Note: Oksman since has moved on to lead U.S. marketing at Reebok.)

]]>

Photo: Webb Chappell

Throughout her life, Sandra Graham has played at least 15 instruments. Piano was the first.

Sandra Graham, associate professor of ethnomusicology, credits a brief romance in her mid-30s with bringing her back to music. Not that her love for music ever really waned. She grew up singing around the piano with her parents and four siblings, and she began playing piano and clarinet as a youth, adding instruments, such as the bassoon, as her curiosity arose. Her bandmates were her best friends.

But a move from New York to Maryland when she was 13 changed more than her surroundings. “I hated my band teacher,” she says of her new school, and the music teacher didn’t challenge her abilities. So Graham’s interest dwindled. She continued adding to her repertoire of instruments, learning guitar, but by the end of high school, Graham decided her college major would be English. Upon graduating, she worked as an editor and was content playing piano and attending theater for her musical fixes. Then she started dating an actor. “It was just one of those little three-month romances,” she says, “but it had a profound effect on me, because we’d spend Friday nights at his grand piano playing duets and singing show tunes. It reignited my love of music.”

Graham decided to earn a second degree from Moravian College in musical composition “for the fun of it.” After arriving on campus, however, the myriad possibilities entranced her, and she immersed herself in as many ensembles and courses as she could, once again learning to play new instruments. “I had to take courses in all the instrument families,” she says. “But every once in a while I would fall in love with an instrument and take private lessons. I took viola and oboe because I just really loved those.”

When graduation loomed, Graham couldn’t bear the thought of school ending, so she applied to graduate school and set about earning her doctorate from New York University, where she discovered ethnomusicology, or the study of music in culture. “Ethnomusicologists still attend to what music sounds like, music analysis, theory, all those things,” Graham says, “but we also look at what social meaning the music has. Does it have implications for gender, politics, religion, social organization? Ethnomusicology was a word that had never passed my lips. And I fell in love with it.”

During grad school, Graham continued learning instruments, picking up the mandolin and playing in a Near and Middle Eastern ensemble. “I sang and played various string instruments,” she says. For her dissertation, she chose to focus on the Fisk Jubilee Singers, the first African-Americans to sing spirituals on a public platform to a white audience. Her research has taken Graham down “all these little alleyways,” and she has written about blackface minstrelsy, black music theater, and the politics of folklore in America. Currently, she is finishing a book on the popularization of African-American spirituals.

After earning her PhD, much of Graham’s time was dedicated to launching the graduate program in ethnomusicology at the University of California, Davis, where she taught for eight years. During her time at UC Davis, Graham traveled extensively and taught for a semester in Slovenia and Croatia. “The folk music really stuck with me,” she says of her time abroad. “There were folk music festivals, and holidays that included folk music. The songs are indelible in my mind because music plays a role in public rituals and holidays in these countries in a way that it doesn’t in the United States.”

Four years ago, in search of a new, more permanent role, Graham brought her knowledge and talents to Babson. “It felt very much like home here,” she says of the College. “What attracted me is there is no department of music. It’s very stimulating to have this cross-pollination of discourse among music and poetry and anthropology and Middle Eastern studies and African-American studies and feminist studies.”

Since arriving, Graham has developed and teaches four courses: “African-American Music,” “Appreciating Classical Music,” and “Global Pop,” as well as “Memory and Forgetting,” which is part of the first-year foundation curriculum in arts, history, and society. Although she wasn’t sure what to expect from business majors, Graham says Babson students often bring a greater degree of interest to her classes than her previous students. “When you’re teaching music majors, a world music course can be just another requirement they have to fulfill. Some may be interested, some not. Here, most of my courses are pure electives,” she says. “The people who are there want to be there.”

Graham also is involved with The Empty Space Theater, Babson’s cocurricular program that integrates theater and the classroom, becoming its music director. Her stint began in 2012 with the musical Working, based on Studs Terkel’s nonfiction book about Americans and their jobs. “I had my students do interviews with people like Studs Terkel had done. They taped the interviews, they wrote them up, and I published them in a book. Then I had my students invite their interviewees to a performance of Working,” says Graham. “I threw a reception for everyone afterward. It was a wonderful event. We had a blast, and I was just bowled over by the transformation of the students. I thought, ‘Oh, I can’t wait to do another one.’”

Even with such a full schedule, Graham also said yes to the Rocket Pitches, Babson’s student a cappella group, when they asked her to become their faculty adviser. Graham says she functions more as a director, finding music for the group and teaching them songs. About 20 students participate. “A lot of these kids come from strong theater and music programs at their high schools,” she says. “They come here and are wondering where they can unwind and have a good time with music.”

Graham, who admits that her full life can be a bit stressful at times, too, is happy to help these students find respite through song. “People come to rehearsal stressed, and then after a half-hour of singing they’re up and joyous again,” she says. “It’s wonderful. We need more of this on campus.”

]]>

Illustration: Harry Campbell/theispot.com

On a Tuesday evening near the end of the spring semester, Clayton DeWalt puts the Babson Music Collective through its paces. “I have a new composition,” says DeWalt, the group’s director, as he hands out sheet music to the student musicians. The piece is Epistrophy by Thelonious Monk, and DeWalt goes about the nitty-gritty work of hammering out each musician’s part. Once the students are ready to give the tune a whirl, DeWalt counts, “one, two, three, four,” and off they go.

DeWalt came to Babson in January to launch the collective. He doesn’t find anything unusual about playing jazz at a business school. “It makes sense to me,” says DeWalt, a doctoral candidate at New England Conservatory and a freelance trombonist who plays throughout New England. “Improvisation and entrepreneurship go hand in hand.” The collective’s goal is to give students a place where they can grow and take chances as musicians. “The most challenging part is convincing people to be open-minded about what they can do on their instrument,” DeWalt says. “It takes time.”

Olivia Belitsky ’17 plays the vibraphone in the band. She took up the instrument in her middle school orchestra, though she originally wanted to play drums or piano. “There were three drummers and five piano players, so my band director decided to put me on vibraphone instead,” she says. “I had never heard of a vibraphone.” As she plays, she holds four mallets that seem to hover over the bars like magic wands, conjuring up notes that swirl around the room. “The vibraphone is a beautiful blend of piano and percussion,” she says.

Chris Bruno ’17 plays saxophone and piano. After the band takes on Epistrophy, he gets to shine on You Know Just Because, a moody piece by Jim Black that makes one think of shadows and dark streets. “It sounds like something that should be in a Quentin Tarantino movie,” Bruno says. Bruno’s musical education first focused on classical music, but then at the age of 13 he took a jazz lesson. “After that lesson, I realized there was more to music than just reading notes on a page,” he says. As he plays You Know Just Because, Bruno blows his tenor sax softly, more a whisper than a blare. “That’s perfect,” DeWalt tells him.

Sitting behind the drum kit, Dara Behjat ’15 takes in the scene. While his bandmates try out new pieces, he holds the music together and moves it forward. “As a drummer, you get to listen to everyone else in the band,” Behjat says. “You are the foundation of the rhythm, and you witness people’s artistic expression before you.” Behjat played drums in high school, though he started out singing in the chorus. He soon grew tired of that, so he switched to the jazz band and fell in love. “I believe it is one of the only genres of music where you have a conversation,” he says. “You listen, respond, yell, argue, whisper through the music.”

When the musicians reconvene this fall, they hope to perform often, to bring the fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants thrill of jazz to campus audiences. “That’s the beauty of jazz,” Belitsky says. “No two performances are the same.”—John Crawford

]]>

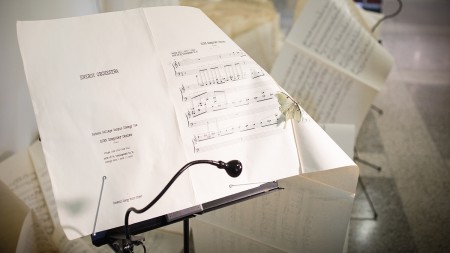

Photo: Tom Kates

The score represents electricity use for one year at Reynolds, Olin Hall, the Babson Skating Center, Horn Library, and the Horn Computer Center.

Flick on a light. Crank up the air conditioning. Turn on the television. Energy is almost like oxygen; it supports modern day life. We use it 24/7. Refrigerators run. Safety lights illuminate. Even when off, some electronic devices draw electricity.

Similar to breathing, we don’t think much about our energy consumption. To raise awareness of energy use, artist Deb Todd Wheeler created Surge, a multi-sensory exhibit that represents one year of electricity use of five Babson buildings. The exhibit, curated by Danielle Krcmar, artist in residence at Babson, includes an audio composition of five musical movements produced from actual data of the five buildings’ electricity expenditure. A video accompanies the composition, to “lure the passer-by into stopping to take in the sound,” says Wheeler. Next to the video projection is a flowing sculpture made from a printout of the musical score (above photo).

While conceiving and developing the exhibit, Wheeler collaborated with sev-eral groups, including Babson facilities, who provided her with the kilowatt-hour energy use of the buildings—a spreadsheet with more than 86,000 numbers. Art students from Wellesley College suggested Wheeler explore working with sound for the exhibit, and sound artist and Emerson College professor Maurice Methot helped her translate the numbers into a composition. Each number, which represents a kilowatt-hour of electricity usage, would equal a note, decided Wheeler, with low-usage numbers being low tones and, conversely, high-usage numbers being high tones.

“The higher tones make the intensity of use an unappealing stimulus,” says Krcmar. “It’s intentional—that kind of getting under your skin. She wants you to realize that intensity of use isn’t something that we should be striving for. The lower pitch is more musical and soothing.”

Four of the movements were played on a digital synthesizer. The fifth was played on the piano by Wheeler’s brother and mother, who are skilled sight readers. The duet brings the digital data back to “analog human energy,” says Wheeler. Several of the videos show their two sets of hands playing. Other videos, which Wheeler both filmed and found, include footage of moths set to the scores. “I used the moth’s innate attraction to light as a visual anal-ogy to our own unquestioning dependence on electricity,” she says. Preserved moths also were placed in various spots on the sculpture.

“In some ways, we are so exposed to data all the time that we are almost a little numb to it,” says Krcmar, “and numbers become like a word that’s repeated too often. We don’t really think about what they mean. The exhibit kind of hits you on a visceral level where your teeth grate a little bit on the high notes and you think, well, maybe those numbers are a problem.” At the same time, the visual sculpture of the composition, while conveying a sense of intensity through its continuous unraveling, is quite beautiful, she says.

Wheeler says the exhibit isn’t overtly telling people what they should think about energy consumption. It is striving to represent an intangible element— energy consumption—via sound and visuals. “Right now use is invisible, abstract, except when the electric bill comes to our homes,” she says. “I guess this is one of the many wonderful things about the value of art in our culture, providing a place for creative experiments that reflect back on the way we live.”—Donna Coco

]]>