Didn’t you almost go into music as well? I was a double major in finance and piano in college. I had a minor in musical composition, too. When I came out of school, I thought, “Do I pursue business or continue with music?” I had two equal loves, and unfortunately, you have to make a choice. I wanted to write music for movies, but if I wanted to study film composition, I would have had to go to California for film school. I decided to stay with finance.

Do you still play piano? Not as much as I desire, but I do want to own a Steinway concert grand piano one day.

Tell me about living in Taiwan. My parents are originally from Taiwan. I always wanted to experience the culture there. So I went to live in Taipei. I studied Mandarin for almost a year and taught English on the side. It was one of my greatest experiences. The people are friendly, it’s affordable, and the food is amazing. I traveled around and ate out for almost an entire year, trying all the different dishes.

What comes in a LobstahBox? We’re selling the full experience. A classic LobstahBox includes the crackers and picks, Wet-Naps, cooking directions, and place mats that have instructions on how to eat the lobsters. We only source from Maine, and we guarantee the lobsters’ freshness. It all ships overnight in a cooler with frozen gel packs to keep the lobsters cool. That’s the key. If you order by 11 a.m. Eastern, you’ll get it the next day.—John Crawford

]]>For many Americans, doughnuts are a much-loved, feel-good food. More than 193 million people ate these hand-held treats in 2017, and a reported 10 billion doughnuts are made in the U.S. annually. Today, system-wide sales for Dunkin’ Brands—which includes Dunkin’ Donuts and ice cream maker Baskin-Robbins—exceed $11.1 billion from more than 20,000 locations worldwide. Dunkin’ Donuts itself is found in 46 countries.

In New England especially, Dunkin’ customers tend to be loyal and maintain a strong, emotional connection to the company, says Kate Jaspon ’98, CFO for Dunkin’ Brands. Jaspon, who joined the company as an assistant controller in 2006 after auditing it in her previous job with KPMG, remembers childhood visits with her family to Dunkin’ to pick up Munchkins. Professionally, she was drawn to the company because of its iconic branding and growth potential. As a Babson graduate and the daughter of a small business owner, she also liked Dunkin’s all-franchise model and the opportunity to work with entrepreneurs growing small businesses.

Given the company’s entrepreneurial bent and penchant for innovation, perhaps it’s not surprising that so many Babson alumni work for Dunkin’ Brands. It’s not unusual to attend a meeting and discover that the person sitting next to you is a Babson graduate, Jaspon says. She and fellow alumni say the world of doughnuts and coffee is fiercely competitive. Staying ahead of competitors in this space requires fresh, innovative ideas, Justin Unger adds. “When we’re trying to solve a business challenge,” he says, “the entrepreneurial mindset is a valuable asset.” But franchise owner Blum also likes to remind his employees to smile and keep it light. “There’s a lot of work to do, and it’s very hard work,” he says, “but this is a fun business.”

The World of Franchises

After graduating from Babson, Blum worked in commercial banking in Boston for nearly 20 years, eventually leading the franchise-lending group for Sovereign Bank, where he backed a variety of franchises, including Dunkin’ Donuts. “The Dunkin’ franchisees I did business with were some of the nicest people you would ever meet,” Blum says. “I think part of me wanted to be part of that community.” Growing up with a father who owned a small business, Blum often wondered if he should go into business for himself as well.

In 2005, one of his clients, John Batista, who had owned Dunkin’ franchises for decades, asked Blum to partner with him and expand Dunkin’s reach in the Cleveland area. Blum and his wife, Gerri, who was then home with the couple’s four kids, decided to say yes. Gerri spent a year in Dunkin’ stores, learning the ins and outs of operations, while Blum wrapped up his bank job and began his own six months of hands-on training. They moved the family to Ohio and opened their first location in Cuyahoga Falls in November 2007. Blum remembers a lot of anxiety and doubt. But when the banking industry tanked in 2008, he was relieved that he had left, and by the five-year mark he and Gerri felt confident in their decision to join Dunkin’. Blum’s brother, Bob, eventually joined the business as a partner, and they now own 26 Dunkin’ locations.

For many Dunkin’ franchisees, doughnuts are a family affair. Consider Alex DiPietro ’09, who met his wife, Lindsey ’08, at Babson. After working in technology sales for several years, DiPietro went into business with his wife’s father, Carlos Andrade, an immigrant from Portugal who followed in his brother’s footsteps and purchased his first Dunkin’ franchise in the Boston area roughly 50 years ago. Over the decades, the Andrade brothers have drawn many more relatives into the business. “I always joke that my wedding ran on Dunkin’,” DiPietro says. “We had 300 people there, and pretty much all of them were franchisees.”

Since DiPietro joined his father-in-law’s business, they’ve expanded from 70 stores to 130, making them one of Dunkin’s largest franchisees. DiPietro manages 13 locations in Massachusetts, 10 in Connecticut, and 13 in Florida. His responsibilities range widely, from overseeing daily operations and building maintenance to staking out new properties and growth opportunities. He believes more people should consider owning franchises. “Coming out of a great school like Babson, everyone wants to create a product or build their own business,” DiPietro says. “But I think franchises are overlooked as an opportunity to own a business. An established brand has already done a lot of heavy lifting, and it allows people to get their feet wet.”

Dunkin’s franchise agreements are typical in the franchise world, explains CFO Jaspon. Franchisees pay an upfront fee per location that is good for 20 years. They also pay ongoing 5.9 percent royalties to Dunkin’ Brands each week, along with a 5 percent fee based on top-line sales, which goes toward advertising. In many regions, multiple owners invest together in cooperative kitchens where doughnuts are made daily and delivered to stores, keeping the process efficient and consistent.

Photo: Gene Smirnov

Franchise owner Adam Goldman ’89 at his West Orange, New Jersey, store

After a significant career in corporate America, including many years as an executive consultant, Adam Goldman ’89 began exploring the possibility of owning a business. “I got tired of being on a plane from Monday through Friday,” he says. “I wasn’t finding any great manufacturing businesses for sale, but I was going to Dunkin’ Donuts every day for my coffee.” Goldman felt the store near him in West Orange, New Jersey, didn’t run as well as it should and thought he could probably do better. With his interest piqued, he began researching franchise opportunities. Dunkin’ Donuts stood out in part because it allowed franchisees some latitude in their entrepreneurial tactics. So in 2009, Goldman purchased two stores in nearby Paterson. He hired more staff, bought updated equipment, and launched new initiatives, such as delivering doughnuts to local offices.

He then purchased a third location in West Orange, but the store felt small and parking was lousy. So Goldman operated out of that Dunkin’ while building a new store just 150 yards away, this one with a drive-thru, ample parking, a kitchen, and quadruple the seating. The new location opened in December 2015. “We operated the old store until 12:30 p.m., and then opened the drive-thru at the new place at 12:31 p.m., and never skipped a beat,” Goldman says.

In an effort to control operating costs at this larger facility, he outfitted the store with green technologies, including LED lighting, high-efficiency heating and cooling, an in-house “biodigester” that breaks down food wastes to produce energy, and an electric-vehicle charging station in the parking lot. The store won Dunkin’s “Green Elite” designation, and Goldman says the West Orange community has loved the new location. “Dunkin’ told us to expect a 30 percent bump in sales due to the drive-thru,” Goldman says, “but we actually had an 85 percent bump in sales.”

Location, Location, Location

The success of Goldman’s stores (he and his wife, Karen, now own four) points in part to the importance of wisely chosen locations. Blum in Ohio prefers to locate his stores on Monday-to-Friday commuter routes, just before the driver hits the highway. “Right turn in, right turn out, you’re on your way,” he says, adding that he also considers commuter psychology. “We prefer to be at the beginning of the commute as opposed to the end. If you’re five minutes late heading out the door for your 30-minute commute, and you know we’re fast, you’ll stop for a cup of coffee even though you’re running late, thinking that you might be able to make it up,” Blum says. “But if it’s at the end of your commute, and you’re five minutes late, you’re not stopping.”

The Babson franchisees say fast but friendly service is critical, particularly at the drive-thru window. Goldman’s West Orange drive-thru serves 130 to 140 cars an hour during the morning rush. Blum coaches his teams to assume that most customers are late to work. Dunkin’ has less of a “sit-and-stay” mentality than other coffee spots, adds DiPietro, and focuses more on moving people in and out. “Our customers have to get to work, have to get the kids to school, and have to move along with their day,” he says. “Speed of service is imperative in our business.”

Competition comes from all directions. The U.S. doughnut universe includes such contenders as Krispy Kreme, Canadian chain Tim Hortons, and local bakeries. But the competition grows especially fierce around coffee and other beverages, which account for more than 60 percent of Dunkin’s U.S. sales. The competition comes from chains such as Starbucks, quick-service restaurants such as McDonald’s, local coffee shops and high-end “beaneries,” and the so-called “C” stores, or gas and convenience businesses, such as Cumberland Farms. “They’re using coffee and other beverages to drive people into their stores,” Jaspon says. “They’re actually giving the product away for very cheap, which has given us a whole new form of competition to deal with.”

Dunkin’ also competes with the coffee maker at home and at the office, Blum notes. “There are so many choices for customers to get a cup of coffee, so we have to execute at as high a level as possible,” he says. In part, this means delivering coffee just the way the customer likes it. “For every medium black coffee there are 30 people who will order it highly customized, say with one Splenda, three creams, and a pump of caramel swirl,” Blum says. “People are very particular about how they want their coffee.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge for Dunkin’ franchisees is the struggle to find good employees. Given the low national unemployment rate, employers face a severe labor shortage. A declining number of high school students—previously a reliable source of workers—apply as well, exacerbating the problem. “Applications are way, way, way down,” Blum says, “and not everyone’s cut out for customer service. I have more anxiety about staffing than any other issue. My wife will tell you: As we get closer to an opening, I get crankier and more and more anxious.” Each new location typically requires 10 to 30 employees, depending on store size and volume.

In the search for solutions, Blum and his brother have traveled to Washington to lobby on franchisee issues such as immigration reform, with the hope that increasing the number of people coming from other countries can expand the pool of available labor. Goldman notes that a large number of his employees are from Bangladesh. “I have brothers, sisters, uncles all from the same families working for me,” says Goldman, whose franchises experience unusually low staff turnover. Most employers are desperate for reliable help, Blum says. “Talk to people in other industries that support us: the carpet guy, the window guy, the landscaper, the snowplow guy. They’re all in the same boat,” he says. “Everyone’s just scratching their heads and struggling.”

We Are Family

Any time multiple franchise owners get together, staffing difficulties are a frequent conversation topic. “We share each other’s pain,” Blum says, who adds that he and other franchisees typically see one another as allies rather than competitors. Goldman says, “In general, we talk, we share ideas, we help each other out. We are more family than competitors.”

That spirit of cooperation also exists at the corporate level, where partnering with franchisees is built into the organization model. For example, Dunkin’ Brands maintains a formal committee system made up of franchisees elected by their peers. Regional Advisory Committees (RACs) elect representatives to the Brand Advisory Council (BAC), which meets with the corporate team in Canton, Massachusetts, four times a year. The BAC also has subcommittees of franchisees to focus on such areas as marketing, restaurant operations, profitability, and technology. “The meetings are useful, as you get to meet and interact with the brand leadership,” says Blum, currently co-chair of the Midwest RAC and a member of the BAC. “You don’t always get exactly what you want, but you get to share your ideas and opinions in a constructive format.”

Franchisees are central to Dunkin’ Brands, which is 100 percent franchisee-owned, notes CFO Jaspon. Dunkin’ does not run any stores itself, which contributes to a smaller-than-usual corporate structure and allows for corporate-franchisee teamwork. “Franchisees are an integral part of every decision we make,” says Anh-Dao Kefor in integrated marketing.

Corporate guides strategy, develops and rolls out new products and promotions, manages advertising budgets, and handles product nutrition information and regulatory compliance, for example, but it solicits feedback from franchisees along the way. This occurs through the committee system and in more informal ways, too. “I might pick up the phone to franchisees and say, ‘Hey, I want to run something by you,’” Kefor says, asking, for instance, about their initial reaction to a new product concept or promotion.

“People think of us as a very large corporate organization,” Jaspon says, “but it’s really a conglomerate of small business owners.” In addition to working with franchisees, Jaspon oversees the team that handles financial planning and analysis, business analytics, and tax and accounting. Her daily duties include managing interactions with the Securities and Exchange Commission and investors, and she handles the finance side of all business functions. “Every day is different,” she says. “I could be in meetings with franchisees, meetings with our investors, or leading the finance group in the office.”

In Kefor’s daily work, she views franchisees as one of the customers her integrated marketing team serves, in addition to the field teams for marketing and operations, who drive the communication and execution of upcoming programs. Kefor’s first roles with Dunkin’ were marketing positions for Baskin-Robbins, and over the next decade she eventually moved into strategic initiatives and operating systems roles, serving as the bridge between the Baskin-Robbins brand and franchisees. “I would spend my commutes every day on the phone with our franchisees, getting to know them, understanding their stores, basically building trust and credibility,” Kefor says.

At the beginning of 2018, Kefor took on her current role with Dunkin’ Donuts, leading the four-person team that oversees the 12- to 18-month marketing calendar for beverages. Her team develops monthly programs to match the season (say, Girl Scout-inspired flavors during the Scouts’ cookie season), partnering with the advertising, loyalty, public relations, and media teams to develop campaigns. Sharing the story and details of each program with franchisees keeps Kefor and her team on their toes. “We’re not developing a product and taking it straight to the consumer,” she says. “We have the opportunity to collaborate with our franchisee partners first. We want them to be advocates and ambassadors, and that requires a strong business case and due diligence on our end to get them on board. I’ve learned that you have to be proactive about franchisees’ concerns.”

Drawn in by Doughnuts

When Nisha Munshi, MBA’15, meets new people, there’s often a funny moment when they ask what she does for work. “When I explain that I’m a registered dietitian for Dunkin’ Donuts, they often look at me with a slightly confused face,” she says. Munshi earned an undergraduate degree in nutrition sciences and went on to Massachusetts General Hospital to complete a dietetic internship. She completed several clinical rotations in different areas of nutrition and discovered that she liked the broad reach she could have while working for food companies.

Photo: Pat Piasecki

From left, Anh-Dao Kefor ’05, Kate Jaspon ’98, Nisha Munshi, MBA’15, and Justin Unger ’08 all work in the Canton, Massachusetts, headquarters of Dunkin’ Brands.

When she began at Dunkin’, Munshi spent much of her time in a regulatory compliance role, compiling information about ingredients to create Nutrition Facts labels, as well as ingredient lists and allergen information for each Dunkin’ product. “Over the years my responsibilities have broadened to strategy, and I’m now developing nutrition-related goals and initiatives for the company as a whole,” she says.

Munshi earned her Babson MBA in part to hone her strategy skills. She also conducts trend research to track better-for-you choices at other quick-service restaurants, monitoring such information as the sugar and calorie content of their products. She shares this information with the innovation teams at Dunkin’. The company already offers options such as oatmeal and wraps with egg whites and veggies, developed in response to customer requests. “We’re always going to have those indulgent products, but consumers are becoming more savvy about what’s in their food, where it comes from, and what’s good for them,” Munshi says, adding that customers should watch for additional options coming soon. Dunkin’ Brands also removed all artificial dyes from its doughnuts and has pledged to remove them from the rest of its menu by the end of this year.

As director of strategic partnerships, Justin Unger also is responsible for reaching new customers, which his team does by linking Dunkin’ Donuts with other brands. They led a recent collaboration with Massachusetts-based shoe company Saucony, which created a Dunkin’-themed running shoe for the Boston Marathon. The shoe designers began with an existing Saucony shoe, the Kinvara 9, and tricked it out with Dunkin’ colors, images of coffee beans and a frosted doughnut, and the America Runs on Dunkin’ logo. The limited edition shoe sold out quickly, Unger says, but the benefits of such partnerships linger. “We wouldn’t necessarily be able to talk to runners the way we did, but the partnership with Saucony made our brand top of mind for new audiences,” Unger explains. “And the beauty of the partnership is that it goes both ways. We are a trusted voice for our audience, so it increases reach for both partners.”

Technology innovations also are key to maintaining and attracting customers. When Unger joined Dunkin’ Brands in 2016, he oversaw its DD Perks loyalty program and mobile app, which rewards customers with personalized promotions and offers. Customers also can use the app to place orders and pay in advance of pickup.

Dunkin’ is not alone in these types of innovations. For example, Starbucks offers a similar app. “We’ll continue to see the industry as a whole lean in on loyalty and innovation and technology and to think about how we can use them to enhance the guest experience,” Unger says. Jaspon notes a recent example of originality: “Our newest store in Quincy, Mass., is the first store in the restaurant industry that we’re aware of where you can order ahead of time, skip the drive-thru line, and go to a separate window to pick up your product.”

In the end, though, a friendly “good morning” still goes a long way in building customer loyalty, notes franchisee Goldman, who says 95 percent of the people in his stores are repeat customers. Blum agrees. “We want people to leave a little happier than when they walked in,” he says. “If we succeed, they come back the next day.”

Erin O’Donnell is a writer in Milwaukee.

]]> There are many ways to be a disruptor, an innovator. Some use technology; some work through politics. Ebru Ipekci ’93 does it with chocolate.

There are many ways to be a disruptor, an innovator. Some use technology; some work through politics. Ebru Ipekci ’93 does it with chocolate.

The Istanbul native worked at Chase Manhattan briefly after Babson, but it wasn’t a fit. “I wanted to be in a business that has no boundaries. I wanted to create something,” she says.

Noticing an unfilled niche in the Turkish marketplace, she started writing cookbooks, teaming up with a partner who had trained at Le Cordon Bleu. The cookbooks led to wider culinary ambitions. “There were no specialty bakeries in Turkey,” says Ipekci. “So we said, ‘OK, let’s create a French bakery.’”

The shop, called Butterfly, opened in 2003 and was an immediate success—so much so that a slew of imitators followed. Looking to innovate, Ipekci began offering a line of high-end, handmade chocolates that eventually eclipsed the pastries. Today, she says, Butterfly is “probably the biggest handmade chocolate business in Turkey.” They still sell pastries—but exclusively chocolate ones. Ipekci was deeply involved in designing her four stylish Istanbul shops, the newest of which opened in March.

Butterfly offers the kind of fashion-forward creations you would expect to find in Paris or New York. Ipekci, whose interests extend to art, design, architecture, and technology, creates new chocolate collections several times a year, reflecting seasonal ingredients and trends in design. She has drawn inspiration from sources as disparate as chia seeds and Turkish Iznik tiles. For her most recent New Year’s collection, flavors included gingerbread, tahini, cinnamon gianduja, and apple caramel.

A consistent best-seller pairs chocolate with pistachios from Gaziantep, the Turkish city famous for those nuts. But Ipekci always tries to push the envelope. “Buckwheat is very popular in French pastry,” she says. “We did it this season—buckwheat with dark chocolate. I loved it, but it didn’t sell much.” That doesn’t trouble her; she knows that educating customers’ palates—part of her role as an innovator—can be a process.

Looking ahead, Ipekci is excited about improving her online presence and incorporating more technology into the business, making it easier to shop on the website and adding worldwide shipping capability. “The sky’s the limit,” she says. “This is what I like about this business. There are no bounda-ries. I keep thinking of new things that haven’t been done.”

]]>

Illustration: Miguel Porlan

A group of 20 chefs from across the country arrived on campus last fall for a new five-day leadership program. Some were restaurateurs; others were bakers or artisanal coffee roasters or sold handcrafted ice cream.

They represented a range of culinary styles, but each had two traits in common: All were women, and all were inaugural fellows in the Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership program, devised by Babson Executive and Enterprise Education for the James Beard Foundation (JBF), the New York-based national culinary nonprofit.

“Like most industries,” says Mitchell Davis, JBF’s executive vice president, “the food industry has a dearth of women leaders at a certain level.” The goal of the program is to support women who want to expand their businesses and hone their leadership skills. More than 90 applicants vied for 20 slots, which were offered as fellowships with all expenses covered by the foundation.

Davis explains that JBF had long sought to create a program that would help women in the field aim higher and imagine what’s possible. When, through a series of connections, Babson appeared on JBF’s radar, it seemed a perfect fit. Candida Brush, vice provost of global entrepreneurial leadership, and Victoria Sassine, adjunct lecturer, served as faculty directors for the program, which takes participants through such topics as managing staff, negotiations, finance, and value propositions. The week culminated with attendees making a final presentation detailing an action plan for growth.

More philosophically, Brush hoped the program would bring about a change in mindset for participants—transform them from puzzle solvers to quilt makers, as she puts it. Chefs, she notes, are task-oriented and tend to focus on the day-to-day. Instead, she says, “I wanted them to think about what it means to be more creative and more strategic.”

Carolyn Johnson, chef-owner of 80 Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts, and Mooncusser Fish House in Boston, was excited to participate in the program. “I came away feeling very motivated and energized and exhausted,” she says, “with a greater understanding of my need to step away from my role as a cook and into my role as a business owner.”

The food industry is demanding for both men and women, but some of its challenges are unique to women. At a session on leadership and gender issues, several of the participants talked about feeling the need to walk the line between being liked and being respected. “That’s the double bind” for women managers, acknowledged session leader Susan Duffy, executive director of Babson’s Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership. “But here’s a hint,” she told the group. “You’re allowed to come back from a program like this and totally become the new boss.”

Brush says that though many of the week’s topics were not gender specific, “There is a benefit to having a single-sex cohort. They have common issues, and a cohort sisterhood is a little different from when you have a mixed group. It’s a safe space where you’re not being judged.” And, she adds, it facilitates forming a network of female peers.

Another participant, Elizabeth Wiley of Meadowlark Restaurant and Wheat Penny Oven and Bar in Dayton, Ohio, says the program was validating and empowering. But perhaps the most valuable takeaway was receiving the encouragement to think big. “The dream of doing what you want and succeeding at it,” she says. “That’s pretty heady stuff.”—Jane Dornbusch

]]>

Photo: Pat Piasecki

What is your approach to nutrition? Be flexible. I used to do weight-loss groups when I worked as an out-patient dietician, and people would say, “Oh, I was bad.” I would say, “Did you rob a bank?” They’d say, “No, I had cake at my nephew’s bar mitzvah” or something. That’s not bad. Foods aren’t inherently good or bad. If you’re a diabetic whose blood sugars are tanking, you need candy. It’s the situation. One of the things my students hear over and over again is it’s the dose that makes the poison. It’s not what you eat; it’s how much you eat.

What attitudes trouble you the most? I’ve become interested in something called orthorexia, which is when healthy eating becomes unhealthy. I’ve added it to my classes, because I think people are becoming obsessed with food. They’re not enjoying it anymore. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to take care of yourself. It’s when you won’t go out to eat because it might not be the right food that it starts to interfere with life.

What’s your goal when preparing a meal? For it to taste good. I don’t deprive myself of things.

Do you have a favorite meal? I love when my husband makes tortillas with beans and eggs and chicken, and he sautes the tortillas and folds them over, and then we have them with apple sauce. There’s something about apple sauce that I really like. The taste in my mouth is like a party.

What do you like to do? Travel. We’ve been to the Galapagos. We went to Antarctica. People think they’ve seen icebergs in Alaska, but you haven’t seen anything until you’ve been to Antarctica. We’re going to the Baja Peninsula in March to watch the great whale migration.

Do you have a hidden talent? No, I’ve been told that everything is out there—I have no secrets. Lately, after this election, I’ve been really sad. But usually what I try to do when I’m in a new situation is find what makes somebody smile, because then I can connect with them. You know, make them laugh. A stand-up nutritionist, as my husband says.—DC

]]>When looking for suppliers, Rogers considers not only the quality and cost of products, but also how well those operations treat the environment and their employees, requirements that align with his personal beliefs in protecting the environment and promoting social justice. “It’s the ultimate commitment to values in business. It’s baked into everything that Whole Foods does,” Rogers says. “We can use the power of business to reward people for the work they do. I get to do that every day.”

Rogers enjoys working for a company with a conscious mission. As a youth, he wasn’t sure such a career would be possible. In high school, he wanted to be an environmentalist, but his father questioned how Rogers could turn that interest into a career. “My dad, who was always supportive but not one to let you get away with anything, said, ‘Well, that’s wonderful, but not necessarily a job. Do you want to be an environmental lawyer, a scientist, an activist?’” says Rogers, who at the time wasn’t excited about any of those options. “Working for a business wasn’t on the list of things to do for someone with my interests.”

Rogers came to learn about such opportunities after graduating from Villanova University in 1997 and taking a job with what was then the New Jersey Office of Sustainable Business. The nascent office, created by Gov. Christine Todd Whitman, helped craft policy recommendations in support of sustainable businesses, as well as locate and expand green businesses in the state. “The idea of sustainable business was a new concept at the time,” Rogers says. “I was exposed to businesses that were doing cool and innovative things, making a difference through the power of business, whether with an environmental product or service or through recycling or energy conservation or organic farming.”

After working for several years in the office, Rogers decided that instead of being the person who helped these companies, he wanted to work at a sustainable company. He also wanted to move to the Boston area. Researching options, he discovered Preserve, which makes reusable and recyclable household products from recycled materials. Founded by Eric Hudson, MBA’92, the company is based outside of Boston in Waltham. “I called up Eric and begged my way into a job,” says Rogers.

Initially, Rogers took a part-time sales position, and in time he became Preserve’s national sales manager. “It was a very formative time for the company. I was involved with all aspects of the business,” Rogers says. Developing partnerships with companies such as Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s, which sell Preserve’s products, Rogers was introduced to the natural foods industry. He also learned about Babson through conversations with Hudson. “I realized that if I wanted to take my career to the next step, I needed some business fundamentals,” Rogers says. So after three years with Preserve, he left to earn his MBA.

But Rogers soon returned to the natural foods industry, taking an unusual job with Whole Foods in the fall after graduating. He became the business development coordinator for Earth University in Costa Rica, a position underwritten by Whole Foods. The job came about after Whole Foods executives learned of Earth University and reached out to see how the two could help each other, says Rogers. “Earth University teaches sustainable agriculture,” Rogers says, “but it also teaches entrepreneurship and business.” As part of its program, the school runs farms that grow a variety of produce. Whole Foods executives had a suggestion. “They said, ‘Why don’t you walk the talk and sell us your products. Sell us your products, and you’ll make money, and we’ll sell them,’” says Rogers.

Unfortunately, the arrangement wasn’t working very well. In addition to cultural and language challenges, says Rogers, Earth University had difficulty meeting Whole Foods’ stringent criteria for suppliers. “They’d be like, ‘We have 10 of these, the cost is $15 each, and we have them this one time.’ And Whole Foods would say, ‘That’s nice, but we need 1,000, and they need to cost $5, and we need to have them every week,’” Rogers says. Whole Foods realized that if it wanted the relationship to work, it had to hire someone to help the school, so it financed a business development position and support staff for three years. Rogers spotted the opening on Whole Foods’ website, applied, and got the job.

Photo: Winni Wintermeyer

Matt Rogers, MBA’05, at Jacobs Farm / Del Cabo

“It was a fantastic opportunity,” he says. “I used all my Babson skills, basically creating a business from scratch.” Rogers focused the business mainly on bananas, figuring out such logistics as how to get the fruit on a boat, how to make sure it was still fresh when imported, and how to get it on trucks and to Whole Foods distribution centers in good condition. “Whole Foods took a risk working with them,” Rogers says. “But many years later, we have bought millions of boxes of bananas from Earth University. We buy almost all of their production from an on-campus banana farm, where they do sustainability research to reduce the environmental impact of farming. And the profits from sales go to scholarships.”

Although he had a great experience at Earth University, Rogers was ready to come back to the States when his contract ended. “I was living in very rural Costa Rica, so the walls were closing in a little bit,” he says. When he told Whole Foods executives of his plans to move on, they offered him a job in their Watsonville, California, office, the company’s main location for produce procurement. “Whole Foods is a truly mission-driven organization,” Rogers says. “It was not a very difficult decision to work for them.”

During his time in the Watsonville office, Rogers has helped develop and implement the Whole Trade Guarantee and Responsibly Grown programs, which address a range of issues aimed at educating consumers about products and ensuring product quality while supporting suppliers, workers, and the environment. The work has been complicated, Rogers says, but satisfying. “We’re consistently dedicated to understanding the food supply,” he says, “and figuring out ways to drive things forward.”

The company’s desire for continuous improvement and long-term dedication to making a positive impact align closely with Rogers’ beliefs. He likes how Whole Foods’ values and mission are built into its business model, saying this frees employees to focus on their jobs. “Whole Foods is very competitive. It is exciting and a fun part of what we do. We want to win, because our success means success for the mission,” Rogers says. “It’s not always part of our daily conversation. It’s just part of who we are.”

Photo: Oliver Parini

Amy Levine, MBA’01, director of marketing, Cabot Creamery Cooperative, at its visitor’s center in Cabot, Vermont

From Nonprofit to For-Profit

As an undergraduate at Skidmore College, Amy Levine, MBA’01, was curious about how and why government policies are implemented, so she studied government to understand how things get done and psychology to explore why people do what they do. After graduating in 1993, she moved to Washington, D.C., and worked for a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization called the Center for Public Integrity, which investigates and reports on corruption at public and private institutions. “It’s bigger now, but at the time I was the fourth employee,” says Levine. “We were looking into the flow of money and politics and how legislation is informed and enforced.”

Being part of a small, grass-roots organization also taught Levine about entrepreneurship, as she worked on everything from investigating organizations to figuring out how to keep the doors open to copying press releases the night before a press conference. She enjoyed the work but soon found it took a toll on her emotions. “I was seeing all the ways in which our country doesn’t work and all the ways in which money leads to decisions—and not necessarily what’s best for the country,” she says. “So I thought, I don’t know if I can do this day in and day out. We were shedding light on important things, but I felt like I needed to have a more positive direct impact.”

She began volunteering on weekends with the Alternatives to Violence Project, which offers workshops on personal growth and conflict management to prisoners, communities, and youths. “I was going into maximum security prisons and teaching inmates about conflict resolution and anger management, but I was energized by working with people,” Levine says. “It made me look at people in a different way, making me realize that in some ways we’re all just one bad decision away from lives that would be very different.”

Through that organization, Levine began volunteering with high school students in D.C. as well. Then, in 1996, a friend told her about a job in Ithaca, New York, serving as a mediator for students in trouble and teaching them anger management skills. She moved and took a job with the not-for-profit Community Dispute Resolution Center (CDRC), where she worked mostly with middle and high school students. “I was loving the work I was doing, but getting frustrated with the system around nonprofits,” she says. “The nonprofits in this community were fighting for a limited number of funds, and this was creating an atmosphere of competition instead of collaboration.”

Thinking there must be a better way to have a positive impact, Levine started reading about companies that are making money but also doing social good. “I realized that if I wanted to make a difference, I needed to learn about business,” she says. So after three years with the CDRC, she left to earn her MBA, coming to Babson because she liked its focus on collaboration and entrepreneurship.

After graduating, Levine moved to Vermont with her husband, who had taken a teaching job in the state, and applied for a marketing position at Cabot Creamery Cooperative. More than 1,100 dairy farms in New York and New England are part of Cabot, which is known for its cheese and dairy products. Soon after arriving in Vermont, Levine was offered the job. More than 15 years later, she is still with the organization. “Previously, I hadn’t been anywhere more than three years,” she says. “Cabot is a great fit for me. I love being grounded in the environment and farming and keeping land open and maintaining that connection to the land. Farmers are the stewards of that. It’s a passion for me. It feels authentic.”

Working for a cooperative can be complicated at times, notes Levine. “Sometimes you want to do something for business reasons,” she says, “but it isn’t right for the farmers, so you don’t do it.” Because the goal of the cooperative is to return profits to the farmers, Levine also doesn’t receive a huge marketing budget like she might at another company. So she and her co-workers take a creative and entrepreneurial approach to spreading their message. Many of the Cabot farmers volunteer in their communities, so the marketing team created programs about engaging and thanking volunteers and encouraging participation. Cabot has a food truck called The Gratitude Grille, for example, that feeds volunteers at the sites where they are serving. Cabot also sponsors a cruise for people who have been outstanding contributors to their communities. “We bring 40 to 50 people on the cruise, and we host some seminars on best practices and volunteering. It’s a great way to bring like-minded people together,” Levine says.

Cabot is a B Corp as well, a certification handed out by the nonprofit organization B Lab, which makes its determination after examining a for-profit company’s social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency. “We’re part of a community that is saying we’re going to look at business as a force for good, and not just a way to meet the bottom line,” says Levine.

Collaborating with other B Corp companies has been exciting, says Levine. She is leading a steering committee of B Corp members who are examining how they work together and figuring out ways to grow the brand so that it becomes more recognizable to consumers. “The B Corp label will help consumers make a choice,” she says. “They can look at our product and say, ‘Oh, they’re a B Corp. I want that.’” Other initiatives at Cabot include belonging to the National Dairy FARM (Farmers Assuring Responsible Management) Program, which sets standards for animal care, and creating a group that addresses sustainability issues (Cabot recently won a U.S. Dairy Sustainability Award).

The challenging work at Cabot keeps Levine interested and busy. “I haven’t tired of it,” she says. Working for a company with a mission about which she feels passionate is important to her. “It’s always been about needing to be whole,” she says. “You don’t want your work life to feel separate from what goes on at home. When I entered the business workforce, I wanted to align my professional life with my true self.”

Levine believes more businesses need to realize that people increasingly want to choose jobs based not just on salary but on what a company stands for. “To attract talent, companies have to change the way they are. People don’t have to make a choice, either live a comfortable life or sacrifice and do good in the world,” she says. “They can align those values. It’s exciting.”

Spurred into Action

About eight years out of college, a book transformed the way John Moorhead, MBA’10, viewed his career. Moorhead grew up in New England, loving family, sports, and the outdoors. His main sport was lacrosse, which he played in high school and at Williams College, becoming captain of both teams and an All-American. During college, Moorhead also developed a greater appreciation for the outdoors, going on hikes in the nearby Berkshires of northwestern Massachusetts. “What a place that was to experience the outdoors and find ways to connect with the present moment,” he says. “It helped me to understand nature.”

Photo: Oliver Parini

John Moorhead, MBA’10, brand manager of e-commerce, Seventh Generation, at company headquarters in Burlington, Vermont

After graduating in 2000, Moorhead moved to Australia and worked for Coca-Cola during the Sydney Olympics. Taking the money he had earned, he then stretched his savings into almost a year of traveling the world, mostly to developing nations. “I had some hair-raising experiences,” he says, “but through my travels it became clear to me that I needed a lot more fundamental, real-life business training to understand the difference between what I was seeing in the U.S. and what I was seeing in these countries.” Upon returning to the States, he took an internship with Cat Partners, a hedge fund focused on small- and mid-cap companies; six months later, he was hired as a full-time analyst.

Fast forward five years, when Moorhead is engaged to be married and making a nice living. A college friend gave him the book Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution. “It was massively eye-opening, relating how much damage we’ve inflicted on the environment and those who can’t speak for themselves,” he says. “But it also detailed what we can do to help. Businesses can play a leadership role in helping people and the planet. Those things don’t have to be mutually exclusive. You can be profitable and mission oriented.”

At work, Moorhead delved deeper into his analyses of companies, examining how they conduct business as well as how they perform. He wanted to figure out how he could marry his personal and professional values, and he took notice of people who were starting to transform business practices: Gary Hirshberg of Stonyfield Farm and Ray Anderson of Interface, heads of corporations that built social responsibility and sustainability into their company models. “The deeper I got into it, the more clear it became that I could play a role,” he says.

At first, Moorhead tried to convince his firm to invest in the clean technology space. “They weren’t ready for that,” he says. “So it was time for me to go.” He talked with his fiancee (now wife) and decided to come to Babson to earn his MBA. “I fundamentally believe that entrepreneurship is the best way to drive systemic change,” he says, “so that’s why I chose Babson.”

While at Babson, Moorhead was president of the Energy and Environment Club, where he worked with the facilities team to bring single-stream recycling to campus and made connections in the sustainability industry. After graduating, he became director of business development for a startup called Banyan Environmental, which had developed a technology for capturing mercury emissions. “At Banyan, we were working all the time. My wife was six months pregnant,” he says. “The company didn’t succeed, but I learned more in that year about each of the operating functions of a business than ever before, and I figured out what I wanted for the next stage of my career. I realized that I loved brand management and marketing.”

From research and Babson connections, Moorhead also had a solid understanding of the sustainability industry. He decided to focus on companies in the consumer packaged goods sector, and Vermont-based Seventh Generation became his top choice. Founded more than 25 years ago, Seventh Generation formulates and sells plant-based cleaning and personal-care products aimed at improving the health and well-being of people and the environment. The company has social responsibility and sustainability built into its core business model and, like Cabot Creamery, is a B Corp. “Seventh Generation was one of the original companies to show that business can enter big markets for products that you use every day and do it in a better way,” Moorhead says. “I was elated to get an interview. It worked out very fast from there.”

Moorhead joined the marketing team and has worked on programs across the brand, most recently focusing on e-commerce. One of his responsibilities is to determine a revised strategy for Seventh Generation’s online shopping experience. “The online experience for a consumer is so different from their in-store experience. How do you make sure you understand this and address the needs of the consumer without driving up cost?” he says. “I developed an innovation agenda that I presented to the board in September. We’re resetting the way we think.”

Before tackling e-commerce, Moorhead focused on the baby business. During that time, one of his responsibilities was brand-building partnerships, and Moorhead helped connect Seventh Generation with Mamava, a developer of lactation suites that make breast-feeding in public places, such as airports, easier. Seventh Generation sponsored several suites. “We’re a business with a social mission, and we support moms. The deeper I got into the issue of how difficult it can be for women to find clean places to breast-feed when traveling, the more I realized it’s just a sad state,” Moorhead says. “I’m really proud of the inroads we made.”

Seventh Generation recently was purchased by giant consumer-goods company Unilever. Moorhead expects change but also believes that everyone, including the top executives at Unilever, is on board with preserving Seventh Generation’s core identity and mission. Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, has been recognized by industry observers for his efforts to make Unilever more sustainable and socially responsible. “Unilever will strengthen our ability to scale the business,” says Moorhead. “We need to appeal to more mission-oriented consumers. We also can do a better job of getting our products into the hands of people who can’t afford them. There are still lots of untapped opportunities for us.”

Moorhead believes in the future of companies like Seventh Generation. He knows being socially, environmentally, and financially responsible can be challenging, but that makes him more determined to succeed. “We can’t just come in to work and think about cost and performance. We have to think about the environment and personal health, too. We work really hard at it, from our research and design teams up through senior leadership,” he says. “But once you take a bite, you can’t go back. I’ve always been a passionate and purposeful person who is team oriented. Our mission is to inspire a consumer revolution that nurtures the health of the next generation. I have loved that process.”

Moorhead views Seventh Generation as a model for what businesses must do to continue to evolve. “Coming from an investment space and seeing as many companies as I have, I can tell you that the fastest and largest way to scale impact is a for-profit that stands for something,” he says. “Every time I go outdoors, I think about what I am going to leave for my kids. When they get older, I think they will really respect what we’re trying to do.”

]]>

Photos: Pat Piasecki

IT’S SO EASY IF YOU STUDY. • It’s jelly inside for Big Papi. Does Papi like jelly? I don’t know. Dunkin’ Donuts came up with that. • I don’t know why I can’t remember the stupid combination. • I want to live in a warm city. • We should sneak onto the Wellesley Country Club at night and map the greens. Just putt all night. • These are good fries. • YOU GUYS ARE SUCH NERDS. • How was your summer? It was great. Did investment banking. Long hours. • I know that you’ll be honest. Some people are afraid to say whatever. • Hey. Want to do me a favor? • THE PLATE IS ACTUALLY BIODEGRADABLE. • I’m a problem-solving student looking for opportunities. • THEY HAVE A HELICOPTER PAD ON THE GOLF COURSE. THEY LAND, PLAY, AND THEN TAKE OFF. • It’s hard to study when you’re hungry. • Wish me luck on my interview. • Wait. Did you know he has a girlfriend? • How are things going with your business? I got the message from my lawyer that I got my trademark. • How many pairs did you bring to school? 12. • Yeah, I was in New York City … well, I was living in New Jersey. • I haven’t been in here. They have sushi? • TIME FOR ME TO BOOGIE ON OUT OF HERE. • WE’RE TRYING TO HAVE IT OPEN BY THE TIME WE GRADUATE. • Have a great day. Stay out of trouble. I am trouble.

]]>But about three years ago, on somewhat of a whim, he and Kate Troiano ’07, now his wife, moved to St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. The couple, both of whom had been commuting to jobs from Boston, were in need of a change. Corporate life and city traffic, especially during Red Sox games, had become tiresome. So after exploring a few islands and falling in love with St. Thomas, they decided to pick up and go.

Kate would keep her job at a communications firm and work remotely. But K.J. decided first to figure out life on the small island, which has a population of about 51,000 and measures only 13 miles long by 4 miles wide. He wanted to get to know the people, culture, businesses, and communities, and then devise a plan. “Kate and I come from small towns, so we know how much it means to become part of the community,” says Neilson. “I wanted a sense of the needs and what’s missing before leaping into anything.”

To keep track of his ideas, Neilson scribbled them in a notebook. High electric bills for their apartment led to energy-efficient light bulbs. Tourism drives the island’s economy, so he jotted down charter boat company and provisions for condos. He even thought about aerial drone production and photography for TV and commercials. But one problem soon stood out from the rest: lack of fresh produce. “It’s such a difficult task to get fresh produce consistently,” Neilson says.

Agriculture on the island, with its steep grades and hilly terrain, is sparse. Poor soil quality makes growing nonindigenous plants even more difficult. In nearby St. Croix, where the terrain is flatter, several conventional hydroponic farms have fared well, says Neilson, but St. Thomas can’t easily receive the goods because ferry service doesn’t exist between the islands. “To get products between the islands, you have to fly them or arrange for a freight boat, which is difficult and expensive. So you end up shipping produce from thousands of miles away,” he says, “which results in poor food quality, inconsistency, and high prices.” Residents and tourists alike, he believed, could benefit from locally grown herbs and vegetables.

As someone interested in turning around inefficient systems, Neilson was familiar with hydroponics as well as the urban agriculture movement. “When I was in real estate, I was interested in retrofitting apartments with energy-efficient products,” he says. “I would keep tabs on industries and companies that take a traditional idea, add technology, and make it more efficient. I’m passionate about it.”

St. Thomas, he realized, has similar challenges to some big cities—lack of space, quality soil, and natural resources (in St. Thomas’ case, fresh water). Electricity also is scarce and expensive on the island. While researching urban agriculture, he came across CropBox, a company in North Carolina that outfits shipping containers with computer technology and modified hydroponics to create smart, environmentally stable farms that can grow produce year-round in any climate. The company claims a 320-square-foot crate can produce as much lettuce, herbs, and greens as a conventional acre of land using 90 percent less water, and crops can be planted up to eight times a year.

Photo: Winnie Au

The 320-square-foot CropBox can produce as much lettuce as a conventional acre of land.

Neilson flew to North Carolina to meet with the owner and see the product firsthand. He also visited one of the company’s farms in Naples, Florida, which was at the Ritz-Carlton and being used by its chefs for lettuces. “They blew my socks off,” he says. Upon returning to St. Thomas, he began running the numbers. He talked to chefs and buyers and distributors and friends, asking everyone what they thought. “The more I talked to people, the more I decided that this would be a fantastic idea,” he says.

Now the next step, says Neilson, is proof of concept. The entrepreneur knows he won’t be able to convince potential backers without an actual crop. “The islanders have had so many people make promises but not follow through. They’re used to being disappointed,” he says. “Everybody is skeptical until they’ve seen it themselves.”

Photo: Winnie Au

Kate and K.J. Neilson fell in love with sunny St. Thomas. In the future, K.J. wants to take advantage of the island’s beautiful climate and use solar energy to power the farm.

So he and Kate are funding the startup. They’ve rented land, worked with the government to obtain the permits for electricity and water, and set up their crate. To figure out what to grow, Neilson worked with distributors and restaurants. He planted the first crop in July and by the end of August hopes to be supplying about 3,500 heads of lettuce each month. In terms of labor, minimal training is needed to operate the CropBox, according to its creators, and it doesn’t demand many man-hours. But Neilson wants to see how everything plays out during the coming months.

If all goes well, he has big plans for the future. “You can stack these containers, so I can have 20 containers sitting on a single acre. My goal is to have a large-scale hydro farm supplying specific types of produce so the island no longer has to get them from importers,” he says. Solar also is part of Neilson’s larger plan. When he takes the operation full scale, he wants to own three to four acres of land, half for farming and half for mitigating costs, which would include installing solar panels. Kate will help with public relations, marketing, and raising capital.

Despite encountering bureaucratic hurdles, Neilson already is thrilled with the new venture. “I love the process,” he says. “I like bringing in a container and figuring out the technology and how to grow and scale.” Since the CropBox arrived, people have started to show a lot of interest, too. “I’ve had people come up to me and say, ‘Hey, I heard about the farm,’” says Neilson. “It’s such a big thing down here, to change people’s perceptions. Everywhere I go, people can’t wait until it’s running.”

He and Kate are excited to bring a needed product to the island as well. “Whether you’re visiting for a weekend or living here for 10 years, once we get to scale, you’ll be consuming our products,” he says. “If we can help the island to be self-sustainable, that would be one of the greatest opportunities.”

Photo: Jason Keen

Joe ’15 (left) and Tom ’08 LaGrasso inside their Freight Farm

In the Heart of the City

Back in the United States, far away from the balmy Virgin Islands, LaGrasso Bros. Produce distributes fruits and vegetables to customers in Michigan and northern Ohio from its Detroit headquarters. The family-owned distributor has been operating for more than 100 years, serving mostly restaurants but also schools, hotels, and other businesses. Upon graduating from Babson, Tom ’08 and Joe ’15 became part of the fourth generation to join.

Both brothers worked in the warehouse, a 40,000-square-foot refrigerated facility, while growing up. “The summer before high school,” says Tom, who is now chief operating officer, “my mother gave me the option. You can work at McDonald’s or with your father in the business. So it was an easy decision.” The business suits the brothers. No two days are alike, they say, because their responsibilities are so varied. “You never know what tomorrow will bring,” says Tom.

Joe can attest to that. “I don’t really have a title,” he says. “I do so many things.” During high school and college, he loaded trucks in the evenings. After starting full time, he managed the fleet of 80-plus trucks and trailers that make deliveries. He since has added purchasing to his list of responsibilities and has begun dabbling in sales.

And, as of last fall, Joe became head farmer. Tucked in the parking lot behind the warehouse is a 40 by 8 by 9.5-foot shipping container, similar to the Neilsons’, where the LaGrassos grow lettuces for some of their high-end customers. “We noticed a push in the marketplace for local produce,” says Joe. “People want fresh, sustainable, local produce.” The LaGrassos wanted to fill that demand, but, living in Michigan, found it difficult to locate produce outside of the state’s short growing season.

Then they heard about Freight Farms from a good friend who also is in the produce distribution business. “Ted of Katsiroubas Brothers in downtown Boston talked with my brother about the Freight Farm that they were using,” says Joe. “I was able to go see his farm.”

Walking into the container, Joe thought, “What? Wow.” Towers of lettuce were hanging from the ceiling. Freight Farms uses a vertical hydroponic growing system that is computer controlled for year-round growing. The company claims one of its farms on average can produce as much lettuce as an acre of conventional farmland. But, unlike farmland, the container can be harvested from eight to 12 times a year. “At that point we were curious,” says Joe, “so we did more research.”

Tom crunched numbers, and Joe looked into the logistics. “A lot of my end of the work was figuring out can it be done, and, if so, how would we do it?” says Joe. The LaGrassos didn’t want to hire anyone, which would add to the cost of the farm. If Freight Farms’ labor estimates of 15 to 20 hours per week proved true, Joe figured he could handle most of the work. As backup, both Joe and Tom would attend the training offered by Freight Farms, and Joe also would train his sister, Catherine, who works for the family business, as well as a couple of employees.

Photo: Jason Keen

Tom (left) and Joe LaGrasso both say working in the farm helps clear their heads. Joe estimates that at any one point about 3,000 plants are growing in the container.

The brothers decided the opportunity to provide customers with fresh produce 52 weeks a year was worth the risk. In September of last year, the farm was delivered. The plan was to create a lettuce blend, so Joe began experimenting immediately. “We wanted a product that would be beautiful, tasty, colorful, and of a sufficient weight so a chef could use it on a larger scale,” he says. “We went through about 24 to 25 varieties of lettuce. We’d plant, and then it’s the sit-and-wait game.”

When planting, which is done by hand, Joe uses a pelleted seed, which means the seed is surrounded by clay, making it bigger and easier to handle. “If you don’t want to use tweezers and a petri dish, then you need a larger seed,” he says. The seeds germinate for about a week, and the seedlings then sit in a trough for two more weeks until they are mature enough to go into the tower. About four weeks later, the lettuces are ready for harvesting. “We have a running schedule so that when I’m pulling heads of lettuce out of towers,” says Joe, “new seedlings are going in. Babson’s operations class came to fruition.” At any one point, about 3,000 plants are growing in the farm. Joe says their special blend comprises eight types of lettuce—light and dark greens and reds—and has a spicy, nutty flavor.

As with any new endeavor, the farm has presented the brothers with challenges: a problem with the pumps, a malfunctioning air-conditioning unit. But Freight Farms offers support, as do other farmers using the system. “There’s a Facebook page that everyone who has a farm is invited to join,” says Joe. “You can post things like, ‘Hey, did anyone see this issue with their pump?’ ‘Yeah, I had that two months ago, and this is what I did.’”

The brothers say it’s too soon to determine how profitable the farm will be. Week to week, harvests vary, says Tom, and demand may change during Michigan’s growing season. He is taking a longer view, tracking data for a year or two before determining where the farm stands. Regardless, the LaGrassos don’t expect the farm will ever be more than 1 percent of their volume. Becoming full-time farmers was not the goal. “Our lettuce blend is for someone who is willing to pay a premium,” says Joe, “and our customers absolutely love it. When we harvest, we leave the roots on and dip them in water as we’re packaging, so the plants are still living when the customers receive them and can continue living and growing for a week in a cooler. It stays fresh until the chef decides to serve it.”

Joe never thought farming would be part of his job. “I had never grown a thing in my life before that farm landed on my lot,” he says. “Not a flower. Nothing.” But he loves his time with the farm. Inside the container feels like a different world. Often while harvesting, he’ll listen to podcasts. “It’s a time to get away and think about things other than work,” he says. “I’ve learned a lot. I also like seeing the reaction of chefs and managers who walk into the farm. They’re shocked when the lights go on and think it’s the coolest thing ever.”

Ideas Grow into Reality

Photo: Jennifer May

Before leasing 2.5 acres in New York to start a farm, Jesse Tolz ’08 trained for three years, studying such topics as biodynamics, plant breeding, and seed saving.

Jesse Tolz ’08 remembers the gardens that his mother and grandmother planted and cared for when he was a youth. Dense, magical gardens of flowers, shrubs, and trees. Although he loved hanging out in them and even helped a bit with the tending, he didn’t have as strong of a connection to nature then as he does today. Last year, Tolz leased 2.5 acres to start Vida farm in Ghent, New York, where he grows and sells vegetables, herbs, flowers, and seeds. “I would not have seen this one coming,” he says of his venture.

As a teenager thinking about college, Tolz had envisioned opening a cafe and boutique one day. His high school counselor told him, “You want to be an entrepreneur,” and guided him to Babson. After graduating, Tolz worked in marketing for a few years and landed in Brooklyn, New York, where he planned to open a vegan baked-goods company. He decided to drop by Brooklyn Boulders, the rock-climbing venture started by fellow Babson alumni, including Lance Pinn ’06, to see how his friends were doing. “Lance convinced me to start working at Brooklyn Boulders,” says Tolz. “I think my going there was serendipitous.”

Tolz enjoyed working for the company, and, as it grew, he participated in discussions about how to potentially expand and scale. “I was working for Lance, and we started discussing our core values,” says Tolz. “There was an exercise where we designated our most positive and negative experiences of our lives on a chart.” All of Tolz’s positive experiences were tied somehow to nature. “It got me thinking,” he says.

At Brooklyn Boulders, Tolz definitely saw a great future, with room for growth, creative freedom, and financial stability. But his intuition still told him to leave and follow his interests in the food system by exploring agriculture. “Over the years,” he says, “I’ve learned that the more I trust my intuition, the better things go for me.”

During the next three years, Tolz trained to become a farmer. He took courses at The Pfeiffer Center, a nonprofit that focuses on biodynamics, a holistic and ecological approach to agriculture. He learned about draft-horse powered farming, as well as other skills, such as orcharding, beekeeping, carpentry, and welding. “To be a farmer,” he says, “you have to be a jack-of-all-trades.”

Photo: Jennifer May

As part of his studies, Tolz did a research project on plant breeding and seed saving. “It was one of those rabbit-hole experiences,” he says. “I realized that hardly any farmers who produce crops actually produce their own seeds to improve the plants year after year.” To learn more, he worked for the nonprofit Turtle Tree Seed Initiative, which uses biodynamic methods to grow seeds, which it then sells. Next, Tolz worked in the fields at the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture, a nonprofit farm and education center.

Feeling confident in his skills, Tolz made plans with a partner to start a draft-powered farm near Albany. But the day Tolz packed his car to move, the partner backed out due to financial problems. Tolz moved anyway. “I tapped my network, walking around and talking to people and asking if they knew of any good opportunities or farmland,” he says. “As I did this, I was realizing more and more that it was a sign for me to see if things I wanted to experiment with I could now take up myself.” He found a couple with farmland who were raising chickens and pigs and who wanted to lease land to a plant-based operation. Around the middle of March last year, Tolz signed on, and he began working as soon as the snow melted in late April.

Tolz had numerous ideas floating in his head, but one of his main goals was to set up a farm that wouldn’t demand a huge initial capital investment. “The minimum you usually need to get started is around $100,000,” he says. “You need to buy tractors, fencing, irrigation. You have all these requirements, but you still have to sell at commoditized prices. People expect to find the same prices as at the supermarket. So there’s not that much elasticity when it comes to pricing.”

Falling back on what he had learned, Tolz believed he could create a scalable, replicable system with capital costs of around $15,000 and aims of profitability in year two. To start, he rented a tiller and opened the land, which formerly was a hayfield but now was overgrown with weeds. After cutting up the top layer of the soil, he planted 10 low-growth legumes to become a permanent cover crop. “With a permanent cover crop, you don’t necessarily need to rely on irrigation,” says Tolz. “The cover crop itself has an absurd amount of surface area, so every morning, the dew is collected in these overlapping layers of plants,” he says, effectively watering the field while shading the soil from evaporation loss.

Also, because of the root system and diversity of plants, the soil is healthier. “If I have bare soil, there is more evaporation and runoff, not just of moisture but also of nutrients and soil life, which is bacteria, fungi, all kinds of things,” says Tolz. “There is such an invisible diversity of life. With bare soil, that’s more depleted.”

Tolz uses no pesticides, conventional or organic. The farm also is completely direct seeded, which means every seed goes into the field. Many farms, especially in the north, start plants in greenhouses and then transplant them once the weather warms. “Every time you repot a plant into a larger pot or soil, there is some degree of root shock,” says Tolz. “The idea of sowing directly is once the plant sends out its root system, it’s unrestricted by plastic walls. Not only am I cutting out the infrastructure needed to start plants indoors, my plants are healthier and more delicious. With tomatoes, I don’t know a single farmer who does direct planting of tomatoes. It gives me a competitive edge.”

With a shorter growing season, Tolz has to choose his plants carefully, as certain plants take longer to mature than others. The first year, as part of his experiment, he grew a wide variety of crops. This year, after learning what grows well in his fields, he is focusing on fewer varieties. He also is learning about which crops are more profitable. “Sweet corn, I’m not breaking even,” he says. “But kale and tomatoes have high margins.” To control pests such as deer and rabbits, Tolz has a fence and his adopted dog, Oso, which means bear in Spanish. “I’ve had him for three years now,” says Tolz. “He’s my partner in crime.”

During the season, Tolz has an on-site farm stand for weekend sales and takes orders from restaurants and other customers. In the fall and winter, he’ll sell stored crops, such as winter squashes and dried beans, to restaurants and grocers. Besides vegetables, Tolz is experimenting with developing certain plants for seeds, which he plans to package and sell.

He also has devoted half an acre to flowers, growing 33 varieties. Tolz has high hopes for this revenue stream, which he believes is not as restricted by price ceilings as the vegetables. “People spend good money on luxury items,” he says. He sells his flowers via the farm stand and takes orders from florists and individuals. Some of his flowers are edible, which he sells to restaurants. He has added wedding sales this year and is thinking about a pick-your-own-flowers option. “I’m very taken by flowers,” says Tolz. “Even though I grew up with my grandma and mother gardening, I didn’t see the real value in the aesthetics and beauty of creating a cut-flower setting. But my girlfriend, Marla, is a florist, and she’s shown me a lot about flowers.”

Photo: Jennifer May

Jesse Tolz works the farm—where he sells vegetables, herbs, flowers, and seeds—with his adopted dog, Oso.

For now, Tolz is a one-man—and dog—operation. Early in the year, he prepares the fields and plant beds. In the spring, he begins planting, tending, and weeding. Come harvest time, he waits for the field to cool down before picking, which means going out in the early morning or late evening. All year long, he also does maintenance, manages operations, handles sales and marketing, and continues to learn from other farmers and experiment with new ideas. Once he has obtained proof of his concept, Tolz wants to look for a larger farm, 10 to 30 acres, and add a draft-powered system. “Right now I’m working with small tillers to make the beds in the cover crops,” he says. “Adding horses to a farm system is a plus in my eyes. If you manage them properly, you also get manure, which is a great fertilizer. If I scale up with a tractor, the weight of that machinery would crush and kill the cover crop. Whereas the horse can be super nimble. And I love working with horses.”

Much of what Tolz is doing has no precedent. “It’s an experiment and a lot of risk,” he says. Although his financial investment has been low, Tolz has put in an enormous amount of time and energy. “This is like any entrepreneurial venture,” he says. “I’ve been working really hard, and I’m hoping it works.”

He already has reaped some rewards. Simply being able to put into practice his ideas and ideals has been worth the effort. And he loves the work. “I love seeing the crops, going into a field, and there’s a whole row of beautiful heads of lettuce or tomatoes that are doing astonishingly well,” says Tolz. “I’m interacting with the plants, and although when harvesting you’re ending the plant’s life, you’re giving this delicious product to someone who will be nourished by it and enjoy it. It’s very rewarding.”

]]>“Chocolate reimagined” is the store’s motto, says Shah, who makes each tasty morsel a piece of art. “Chocolate is a combination of everything I love doing,” he says. Grow-ing up, he enjoyed cooking, painting, sculpting—anything that involved creative arts. “My chocolates are visually colorful and textural. They’re also a combination of things I’ve experienced, including flavors from my Indian culture and different cuisines I’ve tried.”

Much of Shah’s inspiration for Xocolatti came from his mother, a talented baker who helped him start the business. Shah says his whole family is full of foodies. “When I make a flavor, everyone is criticizing it,” he says, “but that helps us perfect the flavor.”

For Valentine’s Day, Shah pulls together a special collection of truffles, which includes such flavors as passion fruit (his personal favorite), rose cardamom, and champagne brut. “They’re luxurious and rich,” he says.

Shah, who always wanted to “do his own thing,” credits his education for helping him start Xocolatti. “Babson gives you a foundation on how to start and run a company,” he says, “and then everything is a learning process. You make mistakes, and you learn from them. But once you know how to start a company, you can pursue whatever passion you want.”—Donna Coco

]]>

Our tradition is to spend Thanksgiving weekend on Cape Cod with family in the area. That Saturday, my three children, husband, and I WAKE UP TO GO SEE SANTA ARRIVE BY BOAT in the town cove in Orleans. We all then walk to the local home and garden store, where Santa greets everyone amid displays of electric trains and Christmas decorations. Later that evening, we participate in a candlelight stroll through town and end at a tree-lighting ceremony on the village green. So begins our Christmas season!—Ali Hicks, associate dean of student affairs

Thanksgiving always has been one of my favorite holidays, because my family joins together without any expectations other than love and a good time. Our family has branched out and become quite large, but WE STILL ALL MAKE IT TO THE TABLE FOR THANKSGIVING DINNER. We also are really diverse, and the food options extend past turkey and dressing—potato salad, spring rolls, tres leches cake—adding to my excitement for the holiday. My family isn’t perfect. We are silly and a tad chaotic and somewhat quirky. But we all belong to one family, and Thanksgiving is a great representation of the love and admiration we hold for one another.—Taelyr Roberts ’15

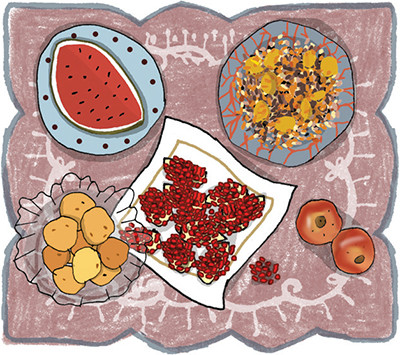

The longest night of the year in the Northern Hemisphere is around December 21 on the eve of the winter solstice. For Persians around the globe, this night—called Shab-e Yalda (translated, the night of birth)—is full of celebration, joy, and fruit. We stay up all night talking, eating, telling stories and jokes, dancing, reading poems. Foods that are absolutely necessary include POMEGRANATES, WATERMELON, AND A BOWL FULL OF MIXED NUTS AND DRIED FRUITS. Though a large portion of this night is spent eating, its magic results from the warm, joyous time spent with friends and family.—Fatemeh Emdad, visiting assistant professor of mathematics

Easter may not be the first holiday tradition that comes to mind, but in my wife’s family, it’s epic. Four generations gather under one roof, and WE FEAST, LITERALLY FROM SOUP TO NUTS. Escarole soup is the first course; then homemade cavatelli pasta; braciole, sausages, and meatballs with sauce; roasted lamb with vegetables and potatoes; then salad. After a short intermission, the eating begins again with fruit, nuts, fennel, coffee, and decadent baked goods. Although the food is reason enough to attend, Easter also lets us catch up and strengthen the bonds that are rarely given center stage in the hustle and bustle of everyday life.—Dennis Lonigro ’00, interactive media technologist