But just a few days later, national events prompted him to put aside that plan. On July 6, a black man named Philando Castile was fatally shot by a police officer during a routine traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. Then on Friday, July 8, Ryan woke to learn that a sniper had killed five police officers in Dallas the night before during a protest against police brutality. “I realized that there was something bigger than my plan,” he says.

Ryan consulted with his core leadership team and sent what he considered to be “a fairly unspecial email” to the company, acknowledging the events. “It said, ‘It troubles me, I’m sure it troubles you, and we don’t have the answers. But I want to let you know I care, it’s on my mind, and we should feel free to talk to one another about it,’” Ryan recalls.

Hundreds of PwC employees responded to Ryan, but one email stood out: A woman thanked him for encouraging people to talk, because when she arrived at work that Friday, she said, “The silence was deafening.” The words were a wake-up call. “Here we were, one of the most progressive organizations in the world,” Ryan says, “yet when the country was feeling down because something bad had happened, our people couldn’t talk about it.”

He decided PwC’s 50,000 employees needed a chance to talk. He chose a day and encouraged everyone to step away from client work for an event called ColorBrave. Employees could converse in groups ranging in size from two to 200 people, but they had to follow a few simple rules: Be respectful, talk about how you feel, and focus not on “right” or “wrong” but on understanding each other.

In Ryan’s group, he heard one black employee describe what it’s like to earn a significant salary yet have people question whether his car really belongs to him. A white employee described the social challenges of her interracial marriage to a police officer. Participants found the experience moving. Someone commented to Ryan: “We shed more tears on July 21, 2016, than we did in our entire 160-year history.”

Babson strives to be an inclusive, intentionally diverse community, from students to faculty, staff, alumni, and external partners. But diversity is a complex issue, says Sadie Burton-Goss, chief diversity and inclusion officer at Babson. “Diversity is about race, gender, ethnicity, nationality, socioeconomics,” she says. Building, supporting, and retaining a diverse community takes commitment, collaboration, and work.

Read More…

Corporate efforts to address diversity and inclusion—usually by hiring employees of various backgrounds, from gender and race to ethnicity and sexual orientation and more—are not new, of course. Ryan notes that decisions by the two PwC chairmen before him laid the groundwork for his leadership team, which includes women, minorities, and an employee who identifies as LGBTQ. The company reports that women make up 47 percent of its workforce and minorities 33 percent. But Ryan stresses that more work needs to be done and that real progress in diversity and inclusion involves more than percentages.

Ryan’s actions, along with the work of other Babson alumni, suggest the dawn of a new era in the effort to diversify corporate America. “We should be the generation of leaders that makes inclusion a reality for America once and for all,” Ryan says.

Diversity Is Good for Business

As a gay black man, Aaron Walton ’83 has always known what it means to stand apart. Growing up in the Boston neighborhood of Roxbury, he was one of the first kids to participate in a program that bused mostly minority children from inner-city neighborhoods to schools in affluent, mostly white suburbs. His parents then moved the family to Bellingham, Massachusetts, where someone circulated an unsuccessful petition to push the African-American family out of the neighborhood. Later, Walton’s parents sent him and his younger sister, Valerie ’85, to a private school for grades 7 to 12 and then to Babson. “At every school, my sister and I were usually the only black kids there,” he says. He often felt the weight of people’s misconceptions and stereotypes, fielding such questions as why he didn’t “sound” black. Back then, he coped by shrugging off those comments.

When Walton joined PepsiCo after graduation, he began to see his differences as beneficial and a source of fresh ideas. His supervisors agreed. Walton started as an analyst and then moved to brand management and the entertainment marketing team, where he was valued as an expert on pop culture and the entertainment business. “Being black and gay exposed me to a wider range of art forms than some of my colleagues,” he says. Walton focused on ways that PepsiCo could use art, music, and film to tell the brand’s story, developing sponsorship deals with acts such as Gloria Estefan, Tina Turner, and Michael Jackson, among others.

Walton eventually left PepsiCo to spend 13 years at his own entertainment marketing agency. But he wanted to fulfill a longtime dream of working in advertising, so in 2005 he co-founded his own agency, Walton Isaacson, with colleague Cory Isaacson and backing from former basketball star Magic Johnson. Walton and Isaacson set out to create what they called “the world’s most interesting agency,” one that celebrates all kinds of diversity. “We understood that diversity ultimately leads to innovation,” Walton says. “When we’re surrounded by people who aren’t like us, we work harder to marshal our arguments to convince people why things need to evolve or be different. That can’t happen if everyone thinks the same, looks the same, comes from the same background.”

Photo: Mathew Scott

Aaron Walton ’83 encourages collaboration among all employees at his agency, Walton Isaacson.

Today the agency employs a remarkably diverse team, with more women than men and staff members who identify as black, Asian, Latino, mixed race, and LGBTQ. Walton is careful not to “silo” or limit his team by, for example, having Latino staff members work only on Latino accounts—an approach that is common, he says, at traditional ad agencies. Clients and employees benefit from exposure to a range of perspectives, he believes. Early in his career, Walton tended to ignore narrow-minded comments from clients, but not anymore. “I finally began to work with clients to explain the negative impact that stereotypical assumptions were having on their business,” he says. “It’s not a difficult concept. Let’s own and celebrate our diversity and all of the amazing things that come along with expanding our view of the world instead of marginalizing these cultures.”

Walton celebrates his own identity and also encourages employees to be fully themselves. “Being able to celebrate all of who we are is freeing,” he says. “People are less focused on conforming and more focused on innovation and being able to provide a point of view that no one else has.”

Diversity efforts at Babson go right to the top. Amanda Strong ’87, a Babson trustee, has worked with President Kerry Healey and others in the Babson community to make the Board of Trustees more representative of people of all backgrounds.

Read More…

Josuel Plasencia ’17 and Yulkendy Valdez ’17 say this level of acceptance is particularly appealing to millennial workers. The recent grads founded Boston-based Project 99, which helps companies teach young employees and their managers inclusive leadership skills, with the aim of retaining diverse talent and growing future leaders. “Professionals of color are three times more likely to quit their jobs, and this is costing companies an average of $6 billion a year,” Valdez claims. “Our idea is that if you’re able to put these millennials—who are going to become three-fourths of your workforce in less than 10 years—at the forefront of cultural change in the company, they are going to be more engaged, they’re going to feel more productive, and they will deliver for your bottom line.”

Studies show that more ethnically and racially diverse companies tend to outperform their less diverse competitors, say Plasencia and Valdez. The same goes for companies with more women leaders; they often have better financial performance than male-dominated competitors.

Plasencia and Valdez both were born in the Dominican Republic and moved to the U.S. as children. Plasencia was raised by a single mother in New York after his father was deported. Valdez lived near Ferguson, Missouri, and often worried about her little brothers when she saw news of a person of color dying at the hands of police. The two founders chose the name of their company after learning about the human genome at the 2014 Clinton Global Initiative conference; President Bill Clinton mentioned that 99.9 percent of human genes are identical, and differences among people account for only 0.1 percent of our genetic material. “We’re always asking, ‘How can you create leaders that embrace that common humanity that we all have but leverage the unique differences that we all bring to the table?’” Valdez says. “Imagine if Josuel was able to talk openly at work about his family, about living with a single mother and having a deported father. Imagine how much more at ease I would feel at work if I was able to talk about how police brutality in the African-American community impacted me growing up in St. Louis. These are the things we’re trying to do with Project 99, to help companies let out the 0.1 percent in all of our cultures so that people can be more engaged and more productive at work.”

Helping employees feel included and respected can be as simple as offering a listening ear, says Minea Moore, MBA’08, director of diversity and inclusion strategic initiatives at Intel. To that end, the high-tech company created the WarmLine, a program designed to help retain employees and staffed by advisers who troubleshoot a variety of confidential topics, especially around career goals. Since 2016, the line has processed around 10,000 cases, and research shows that 90 percent of those employees stay at Intel. Moore adds that hiring and retaining people with different ethnicities, genders, and sexual orientations creates important diversity of thought and different perspectives within a company. This kind of thinking, Moore says, can benefit the bottom line.

Nicole McCabe ’96 is now vice president of strategic initiatives in corporate development at software company SAP and was its global head of gender equality for almost five years. She says companies ignore diversity and inclusion at their peril and offers the example of Uber, which faced a dip in ridership after a female engineer detailed rampant sexism at the company. “You see a lot of these startups that aren’t thinking about their culture early on,” she says, “and then they grow and they’re successful, but they have all of these issues embedded into their culture that create a huge financial risk.”

Commitment at the Top

In January 2015, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich stood on a stage at the Consumer Electronics Show, which attracts almost 180,000 attendees and garners worldwide media coverage, and made a dramatic pledge: By the end of 2018, Intel would reach “full representation” within its workforce. “That means when you look at the makeup of employees inside Intel, it should match the available talent pool outside Intel,” Moore says. In the same speech, Krzanich committed $300 million to support that goal and accelerate diversity and inclusion, not just at Intel but across the technology industry.

Intel’s approach to diversity and inclusion is grounded in data. “We believe that what we measure gets done,” Moore says. “By setting measurable goals based on data, we’re able to ensure that we’re progressing.” These efforts appear to be working: In a total U.S. workforce of about 50,000, the gap to full representation is about 800 people today, down from 2,300 in 2014.

Ryan of PwC agrees that diversity efforts must start with company leaders. “The tone at the top and executive commitment is the single most important thing,” Ryan says. He adds that talented CEOs are particularly well-equipped to tackle tough problems creatively. “They can get transformative deals done,” he says. “They can be entrepreneurial. They can develop new technology. They can raise money and sell companies. When they put their minds to this, they can get it done.”

As a white man who spent his early childhood in the then mostly white Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston before moving to a predominantly white suburb, Ryan may seem a surprising leader in the quest for diversity and inclusion. But he witnessed the Boston busing crisis in the mid-1970s, when a court ordered the desegregation of Boston city schools. The nightly news showed frightening footage of rioters throwing rocks at buses. Images from this confusing time stuck with him.

After the success of the first ColorBrave conversations at PwC, Ryan admits he breathed a sigh of relief and planned simply to continue with existing efforts to recruit diverse talent. But a member of his team pressed him about his influence with companies outside of PwC. What could Ryan do to promote diversity and inclusion elsewhere? “That really, really got me thinking,” he says. As he traveled the country, meeting as usual with PwC clients, Ryan asked CEOs about diversity. “It became clear that many were struggling with how to become more inclusive and were not quite sure how to do it but wanted to do better,” Ryan says.

Photo: Tom Kates

Tim Ryan ’88 talks with employees in PwC’s Boston office.

He reached out to the CEO of consumer-goods company Procter & Gamble and the head of the Executive Leadership Council, an organization for the development of black leaders, as well as to PwC’s direct competitors. Conversations with these leaders eventually led PwC to launch an initiative called CEO Action for Diversity & Inclusion. Participating executives agree to take three steps: to create safe spaces in their companies for conversations about diversity, to provide training about unconscious bias to everyone, and to make best practices for diversity available to other businesses.

More than 360 companies now participate. This past November, 70 CEOs from these companies gathered in New York for a closed-door session about diversity, where leaders were encouraged to talk about uncomfortable topics. “We had an incredible day, where we all left smarter and maybe a little more courageous than we were coming in the door,” Ryan says. As part of its CEO Action initiative, PwC also recently added what it calls the President’s Circle, bringing academic institutions and associations on board. The goal is to engage students, faculty, and staff around issues of diversity and inclusion, given that students are the future employees and leaders of corporate America.

How to Recruit a Diverse Workforce

Finding qualified employees from diverse backgrounds is not as difficult as some people claim, believes Ryan. “I would say that’s one of my biggest pet peeves. We need to do a better job of finding the talent inside our organizations, broadening our recruiting nets and the like,” he says. “There’s so much talent out there in the world. To simply say it’s a talent pipeline issue, in my judgment, is a cop-out.” A CEO Action event addressed this issue, inviting 150 chief diversity officers and human capital officers to New York to share detailed strategies for inclusivity.

Several years ago, McCabe tackled the dearth of women in leadership roles at SAP by scheduling a two-day meeting on the topic. “I brought together everyone who handled core employee life-cycle processes—executive recruiting, our university recruiting folks, our succession planning folks, the people who handle leadership,” she says. “We talked openly about the data and the issues.”

They found, for example, that just 10 percent of employees in SAP’s fast-track leadership program were women. “The intent of the program was to accelerate future leaders, but how can you increase diversity when the primary recruiting pool is not diverse?” McCabe notes. So the group discussed ways to boost women applicants. “It was a great opportunity for everyone to get on the same page and understand the impact of their area on the greater goal,” she says. “Once you put the data up there, no one can really argue with it.” The proportion of women in leadership roles at SAP rose from 19 percent in 2011 to 25 percent in 2017, meeting goals the firm had set six months ahead of schedule.

In April 1998, a Black Affinity meeting at Babson led to the first Black Affinity Conference, now observing its 20th anniversary. Created to engage and retain students, improve recruitment, and re-engage alumni from the black community, the BAC continues to bring people together for learning, networking, and celebrating.

Read More…

Intel hopes that boosting STEM programs in schools will ultimately yield a larger, more diverse pool of technically trained employees in the future. In 2015, the company announced a $5 million investment in the Oakland Unified School District in California, including close partnerships with the district’s largest high school, Oakland Technical, and McClymonds High School, where students of diverse backgrounds make up about 90 percent of the population. The grant funded a new position to oversee the district’s computer science programs and a new computer science curriculum, as well as mentoring and summer internships at Intel. “When you look at how to fill the lack of diversity in technology, you need to start earlier than college,” Moore says. The changes already have helped, she says, pointing to a dramatic increase in the number of Oakland students taking computer science classes in the past two years.

While the company is making steady progress in its efforts to hire women and Hispanic and Native American employees, Intel is still lagging in its goals around the hiring, progression, and retention of African-American employees, Moore says. So Intel is increasing its focus on retention efforts and expanding recruitment at historically black colleges and universities. It also plans to host an African-Americans in Tech Thought-Leadership Summit to consider new ways to attract and keep black employees in these roles.

Plasencia of Project 99 says that one secret to retention is giving young minority employees opportunities to lead projects and teams. “This increases their ability to have a voice and makes them a stronger part of your organization,” he says. “They are more likely to stay and want to grow in the company.”

Companies also need to look at the role that unconscious bias—the judgments and assessments that people make without realizing they are doing as much—may play in hiring, Walton says. “I think every organization has it,” he says. “It helps to start to understand how it impacts your hiring decisions or impacts the clients you go after.” Making diversity “part of the DNA” of a company from the beginning, as Walton and his co-founder did, can help safeguard against such biases. Emphasizing a true willingness to listen intently to other people also is key, Walton adds. “Too often, people enter a conversation with a mental checklist of what they want out of it,” he says, “and their brains check out as soon as they establish that the other person meets their expectations—or doesn’t.”

A growing number of companies offer unconscious-bias training to help workers understand blind spots around diversity. PwC developed its training with Mahzarin Banaji, a Harvard professor and co-author of Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. Ryan describes one scenario offered in PwC’s training: A car crash occurs, killing a father and gravely injuring his son. When the son arrives at the hospital, the surgeon says, “I can’t operate. This is my son.” Many people respond by wondering how that’s possible, given that the father died. But the surgeon is actually the patient’s mother. PwC requires the training for all new employees, as well as for established employees who want to be considered for a promotion. PwC’s President’s Circle also is calling on university leaders to help build diversity and inclusion course offerings into their curricula, and it has created a campus tour called Check Your Blind Spots, which pushes students to consider such issues before they enter the workforce.

Intel’s Moore acknowledges that corporate diversity training touches on sensitive topics. The company offers Managing at Intel, a program that includes diversity and inclusion training for its managers. “This stuff is hard,” she says. “You hear things that may hurt, and those unconscious biases are not an easy pill to swallow. But a healthy dialogue, actually having a discussion about it, is necessary to really drive change.”

Moving Away from Mandates

In her second job out of college, Moore, who is African-American, had a conversation with an older white male colleague. He expressed opposition to what he called “affirmative action” programs, which he believed hurt the employees they were designed to help. After working together for about a year, the colleague gushed to Moore that he was really impressed with her work. “I connected the dots back and realized that he probably thought I originally got that job not because of my capabilities, but because of ‘affirmative action,’” she recalls. “It was the first time that I realized people might be looking at me differently.”

During her career, Moore has seen thinking about diversity and inclusion initiatives change. Instead of viewing such programs as a way to comply with mandates and legal requirements, companies now are more likely to see them in terms of the tangible value they bring to businesses, she says.

Diversity and inclusion experts are working to move employees away from viewing diversity initiatives as an imposition. McCabe of SAP has come to realize that empathy is a key ingredient in making these programs productive. She helped boost SAP’s existing Business Women’s Network, and with a colleague she co-founded the Leadership Excellence Acceleration Program, which prepares women for leadership roles. McCabe notes that in 2016, SAP became the first tech company to earn Economic Dividends for Gender Equality (EDGE) certification, a global business standard for evaluating gender equality.

Sensing a lack of connection among female colleagues, McCabe also established a less-formal collaboration website to build community among SAP women. It features a webinar series, attended by women across the company. She chuckles thinking about the distancing politeness of the first webinars. Within a few sessions, however, attendees grew more candid and started sharing personal stories. One woman talked about a recent cancer diagnosis, for example, and women from all over the world chimed in to offer support. “You could see the trust and support that they started to bring to one another,” McCabe says.

Experiences like those reshaped her thoughts about what makes diversity initiatives effective. “Now it’s more, how do we evoke empathy for people? How can we help our employees have conversations, and, in some instances, relearn the process of agreeing to disagree?” McCabe says.

Photo: Tom Kates

Yulkendy Valdez ’17 (left) and Josuel Plasencia ’17, co-founders of Project 99

Valdez and Plasencia agree that stilted, forced conversations about race and diversity need to be replaced. “You’ve got to turn a transactional conversation into a human conversation again, which is going to be hard because these topics have been so politicized, especially recently, and have become very tense,” Valdez says. “You’ve got to find a way to sit in a room, starting with small pockets of your organization, and just talk about your own personal story. Start there, and then talk about how this has personally impacted you.”

Diversity and inclusion are worthy causes, Ryan reiterates. “It happens to be the right thing to do,” he says. At the same time, corporations will benefit from these initiatives. “When we make our companies more diverse,” Ryan says, “we create our country’s biggest competitive advantage.”

Erin O’Donnell is a writer in Milwaukee.

]]>So the then 14-year-old approached his father, Sari, with a concept for an app. It would let people take photos of their possessions, organize and track them in groups, and either keep the information private or share the collection with others. Collectors then could talk about their passions, follow each other, discover new ideas—just like members of a club.

In some ways, Anabtawi knew his father would like the idea. Years earlier, when the family was on vacation, their suitcase was stolen, spurring his father to think about a similar idea for a digital organizer. “My father dealt with the insurance and all that headache, and he wished he had a private repository of everything that was in the bag. But apps weren’t a thing back then,” says Anabtawi, “and websites were primitive. The best he could do was use an Excel spreadsheet, but that wasn’t intuitive. So he kind of forgot about the idea.”

When Anabtawi explained the app to his father, who also is a collector, Sari immediately saw its value. The private option would allow people to keep track of their belongings, while the ability to make collections public and grow communities would make it potentially interesting to a much broader audience. Revenues would come from data mining.

They named the app Snupps, which stands for Serial Number Universal Protection Protocol System, and in 2011 opened an office in their hometown of London. From the start, Anabtawi says his father treated him as an equal partner. “I was very involved with everything,” he says. When they met with an angel investor, he was in on the pitch. When hiring a chief technology officer and a developer, he and his father interviewed and decided on employees together. At 15 years old, an enthralled Anabtawi would come home from school every day and go straight to the office. In 2014, Snupps launched its app on Android, iOS, and online. With user input coming in, Anabtawi turned his focus to fine-tuning product design and strategy. “Our philosophy is to constantly solve problems for the ideal users,” he says, “and the ideal user of Snupps is me.”

The time also had come for Anabtawi to choose a college. Both a friend of the family and his guidance counselor suggested Babson, and, after some research, Anabtawi agreed. Initially, he was concerned about being so far from the London office, but Anabtawi transitioned. Whenever possible, he would group classes in the morning or afternoon to maximize the time available for work. “Having Fridays off was incredible,” he adds.

Balancing work and school was hard at times, admits Anabtawi, but he also has brought a lot from the classroom to Snupps. Anabtawi participated in the San Francisco program, which proved to be hugely beneficial. “Every class tied into Snupps somehow,” he says. “We had a tech consulting class, where we were helping companies with problems, and a lot of those problems were the same that we were facing. I realized that within the space of three hours, I was actually learning something in class and then applying it to my company.”

One of Anabtawi’s professors, senior lecturer Mary Gale, helped him with his presentation deck. “She looked at it and was like, ‘It’s pretty good, but you have to change the whole thing.’ I said, ‘We’ve been using the same deck for three years. What do you mean, change the whole thing?’ She sat with me for maybe three hours and walked me through it,” Anabtawi says. “I presented it to the office, and my co-workers asked how much I had paid for the advice.”

Back on Babson’s Wellesley campus, Anabtawi valued such classes as “Platforms, Clouds, and Networks” with professor Bala Iyer. The course gave Anabtawi a more comprehensive understanding of the tech infrastructure, helping him see how Snupps fits in and where it should be moving. “I brought these insights back to the office and presented to the whole team, and it actually pivoted our goal for the next year,” he says.

Because he took extra courses, Anabtawi graduated in December, but he is staying in the U.S. until May to attend Commencement. “I want to take this time to figure things out and work on growing Snupps in the U.S.,” he says. Snupps currently has almost 2 million users, but Anabtawi is hoping to bump that number dramatically. To attract new users, he focuses on social media, working with well-known YouTube personalities. Snupps also recently partnered with eBay, making it easy for the app’s users to sell their wares: An icon in the Snupps app lets users upload items to eBay in about 30 seconds, and Snupps gets a cut of what eBay makes. Anabtawi also wants to use the time before Commencement to meet more people. “I haven’t had a chance to network much in Boston,” he says, “and there’s a huge tech hub in Boston and even at Babson.”

Anabtawi liked having other students to talk with about entrepreneurship at Babson, although he concedes that he probably has offered more advice than he has received. “That’s just because I started this process at age 15,” he says. “A lot of my friends are in those shoes that I was in a few years ago. They ask all these questions. I really love talking about the experience and helping people through that stage, because the most exciting time is getting started.”

ENTREPRENEURS OF ALL KINDS

Prabha Dublish ’18

Prabha Dublish ’18 describes herself as “somewhat shy.” At a networking event, she isn’t likely to walk up to strangers and start conversations. She also isn’t fond of talking in front of crowds. Even raising her hand in class feels awkward—all those eyes and all that attention focused on her. “I don’t really fit into the stereotypical mold of an entrepreneur,” she says.

At the same time, when Dublish sees a problem, she acts. As a junior in high school, she noticed that peers who were supposed to be donating time to the community as a requirement for National Honor Society were getting friends to sign off on hours. As someone who cares deeply about social impact, Dublish was bothered by their actions. So at the age of 16, she started a nonprofit called Charity Cycle in her hometown of Seattle. “It shifted the focus from hours to impact,” she says. “I would bring community service activities to our City Hall, play fun music, and make it so people have a good time, but also at the end we got a certain amount of work done. I tried to focus on the impact.”

Standing in front of her fellow students to organize their activities was intimidating. “But it helped me build a lot of the skills that I use today,” Dublish says. “It was something that I loved doing. The organization is still running.”

When deciding on colleges, Dublish knew she wanted to study business, but she wasn’t sure where to go. She learned of Babson from Facebook posts of former schoolmates, applied, and received a Weissman Scholarship. During her first year on campus, Dublish lived in Park Manor Central, and she became friends with Derek Tu ’18. “He was always someone who pushed me to think of different ways to address things,” she says.

Dublish also became intrigued by alumni who had started businesses. “In many ways, it changed their lives, right? But I was curious to see what entrepreneurship looked like in communities where they didn’t have the same access to resources like we do here at Babson,” she says. So the summer after her first year, Dublish used the stipend that comes with a Weissman Scholarship to travel to northern India outside of Delhi, where her family originally is from, and meet with women entrepreneurs in underprivileged villages. “It was an incredible experience,” she says. “It’s not just about the power that comes from starting a business. Obviously, there’s an income stream, but there’s also a huge rise in these women’s confidence.”

Dublish also realized how difficult it was for these women entrepreneurs to get started. With no education or income, they didn’t qualify for loans, and their husbands and families typically were not supportive. Some had received entrepreneurship education through programs run by NGOs, but then they had no access to capital. “They were given a toolkit, but they weren’t given anything to use,” says Dublish. She talked to the women about microloans, but they didn’t like the idea. “They didn’t want to send their hard-earned money back to the United States, which they perceived as wealthy,” says Dublish. Instead, the women would pool their money and give it to other women in the community who wanted to start businesses.

Dublish was inspired by the faith and trust the women had in each other and, upon returning to the States, wanted to mirror their efforts. So she came up with the idea for Womentum, a crowdfunding platform that allows people to donate to women entrepreneurs starting businesses in developing countries. As she often had before, Dublish talked with Tu about her idea. Having started several companies, he was a great sounding board. “Derek is such a powerhouse when it comes to entrepreneurship, and he has a strong marketing mindset,” she says. “I feel like I have such a strong social-impact background.”

Tu encouraged Dublish to move ahead with the nonprofit, and he became a co-founder. He asked his friend and tech-whiz, Aaron Leon, to be a co-founder as well. “Aaron goes to college in Chicago, and he actually built our entire platform,” says Dublish. “We each bring something to the table, which I think is great with our co-founding team.” The trio launched the site before the end of their sophomore years. Womentum is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, so donations are tax deductible, and 100 percent of donations go to the women.

In her junior year, Dublish participated in the Boston Women Innovating Now (WIN) Lab, offered by Babson’s Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership. “WIN Lab was life changing,” she says. It helped focus her vision and made her accountable. At the end of the eight-month program, Womentum went from funding four women in two countries to funding 36 women in six countries. Since then, the nonprofit also has secured four new corporate sponsors.

The long days of running a nonprofit and attending school can be trying at times, notes Dublish. “Sometimes those days are worth it, when your business is going well and donations are coming in,” she says. “But if you have a 13-hour day, and you spent the entire day putting out fires, then having to do your homework is definitely difficult.” Nonetheless, she wouldn’t have done anything differently. Ups and downs build resilience, she says.

Although Dublish may always feel a bit shy when speaking in front of crowds, she has found new confidence since working on Womentum. “One of the most incredible things I’ve learned is that we tend to portray a certain kind of outgoing person as an entrepreneur, but I think I bring something new to the table,” she says. She has pitched in front of hundreds of people, and Womentum even won “Fan Favorite” at a recent pitch event. “I felt like that was such a huge point in my life,” she says. “I remember calling my mom afterward, and she was like, ‘This is so incredible. What happened to my daughter who would never talk or raise her hand?’”

NEVER SAY NEVER

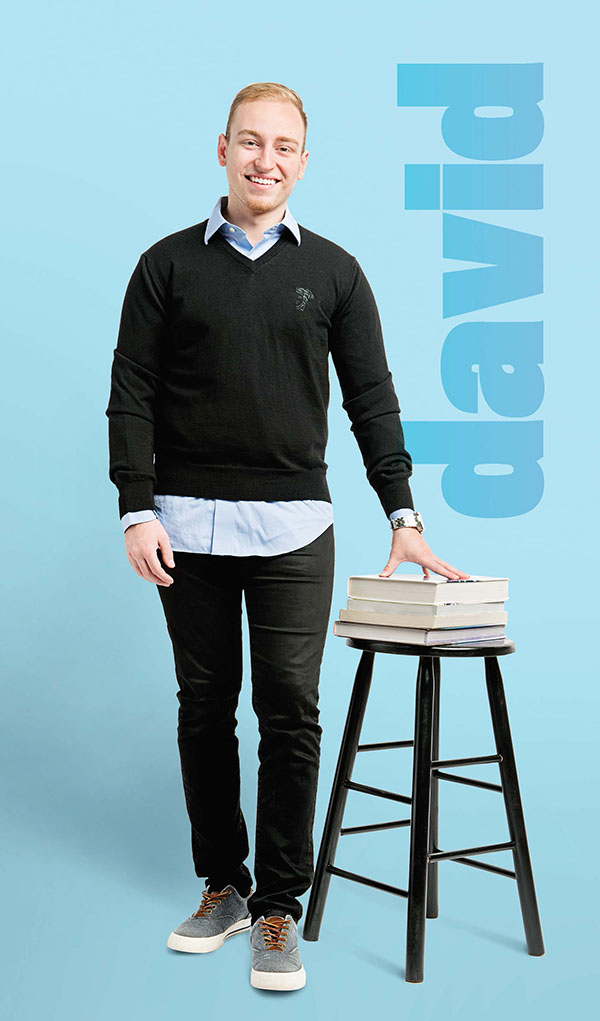

David Zamarin ’19

Ask David Zamarin ’19 where his business drive comes from, and he’ll tell you it began with his grandfather. When Zamarin was 3 years old, his grandfather would come home from work, take off his socks, and offer the toddler a dollar a day to clean them. Even as a child, Zamarin realized that people will pay for desirable services.

Zamarin’s drive to succeed also comes from a difficult childhood. After his parents divorced when he was 2, he lived with his grandparents in a rough Philadelphia neighborhood while his mother worked retail jobs and earned a degree in civil engineering. Eventually, his mother finished her degree and landed a good job, but the years left an impression on Zamarin. “Seeing my mother struggle was tough,” he says. “It kind of inspired me to be entrepreneurial and independent.”

The young entrepreneur started his first “official” business in the fifth grade, buying and reselling popular items such as headphones and watches at flea markets. Then as a freshman in high school, Zamarin applied to a city-run youth entrepreneurship program. “There were 2,000 applications, and 20 were accepted,” he says. “I was the only nonsenior.”

The program provided the aspiring entrepreneurs, who were tasked with starting businesses, with guidance and mentors. Zamarin’s idea for a business stemmed from a pet peeve. A sneaker collector, he hated getting his shoes dirty, so he thought about creating a protective film that could be sprayed on the sneakers. But Zamarin couldn’t fathom how to make such a product, so his mentors suggested starting a shoe-cleaning business. Although initially turned off by the idea, Zamarin came around after doing some research. He named the company Lick Your Sole and focused on university sports teams, contracting to clean athletes’ shoes on a biweekly basis.

Zamarin landed four lucrative contracts and ran the business, which at its peak was bringing in about $25,000 a month, his entire freshman year. He then was looking for a way to scale but didn’t see an obvious route, so once again he began thinking about that protective spray. At the same time, he had an employee whom he paid on commission. “This individual moved to California and wanted to expand the business there,” says Zamarin. “Instead of expanding it, he actually bought me out completely. I sold the company for six figures, which was the most money I ever had.”

With such a successful year, Zamarin became well-known in the Philadelphia entrepreneurial community. “I had a lot of eyes on me,” he says, including serial entrepreneur Bill Green, who had become a close mentor. “I got a good network behind me, and that really motivated me early on.”

Feeling inspired, Zamarin decided to focus on developing a spray. He began researching nanotechnology, which was used by a competitor’s product, and came across the lotus leaf, which has a natural wax coating. He reached out to a friend with a Ph.D. in chemistry, and the friend let Zamarin use his lab after hours. Teaching himself through lessons found on the internet, Zamarin figured out how to decompose the lotus leaf and devised a formula.

But one key was missing. To make the product consumer friendly, the spray had to dry clear. Other sprays already existed, but they dried white. That might be OK for industrial applications, explains Zamarin, but not for consumer applications, such as using the spray on shoes or furniture. While researching production, Zamarin found a manufacturer in Florida whose scientists came up with a 2 percent proprietary addition to Zamarin’s formula that made it dry clear. Naming his business DetraPel, Zamarin incorporated in the summer of 2013 and launched in February of the following year. He was a sophomore in high school. “We ran with it for eight months, hit about $80,000 in revenue, and then my manufacturer went out of business,” he says. “When they filed for bankruptcy, I lost the formula and that crucial 2 percent.”

For several years, Zamarin worked to re-engineer the formula, contacting more than 12 labs, domestically and abroad, and paying close to $100,000 in research and development. “None of them were able to do it,” he says. At the same time, he focused on business-to-business customers who didn’t demand a clear-drying product and brought in six-figure annual revenues.

Zamarin also turned his focus to college. In addition to Babson, Zamarin was accepted at Harvard and the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Then he visited Babson and met professor Joel Shulman, who became a mentor to the young entrepreneur and introduced Zamarin to influential alumni. A scholarship offer sealed the deal. “The network you meet and the connections that you make through Babson—you’ll have those for the rest of your life,” he says.

Despite being drawn in new directions, Zamarin never had given up on finding the right formula. In 2016, during the winter break of his first year at Babson, he went back to the lab where he came up with the original formula, re-examined all the notes and research he’d done in the past, and began testing and tweaking. By the summer, he finally found what he was looking for—a formula that dries clear. “The difference between us and what most people were doing is not only the compounds that we use,” he says, “but also the process that we have for making some of these compounds.”

Zamarin fully relaunched DetraPel in August 2017, starting with the business-to-business market. Now he is poised to scale and take the company to consumers. He has attracted high-level investors, including a deal with Mark Cuban and Lori Greiner after an appearance on Shark Tank, and he also offered his mentors an opportunity to invest. “I count all my success to the help and mentorship I’ve had,” he says. “I’m very loyal to my network.”

Zamarin’s mentors inspired him to help others as well. “I also have to give back,” he says. “I spoke at a youth entrepreneurship conference recently. I want to give other kids the inspiration they might need, because I had that from an early age.”

ACCESS TO EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

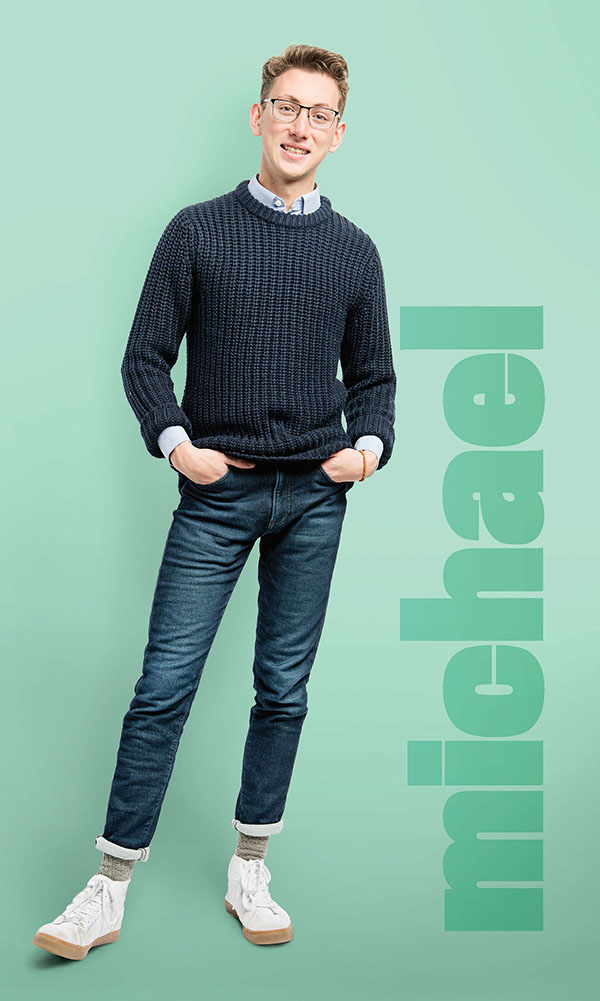

Michael Ioffe ’21

Michael Ioffe ’21 realized at a young age how access to educational resources can positively impact a life. Halfway through the fifth grade, he was sent to Access Academy in his hometown of Portland, Oregon. Although highly gifted, Ioffe wasn’t doing well academically, and this public school specialized in helping children like Ioffe succeed.

The school was a 40-minute commute to the other side of town, but Ioffe immediately felt a part of its community and began to thrive. The school, however, needed funds and support. “The entire school—this vital resource—was in three portables, and that was our only home,” Ioffe says. “The school district repeatedly tried to kick Access out and get rid of the school, because the neighborhood was gentrifying and the elementary school next door needed space.”

Ioffe had an idea. Recognizing that some of his fellow students were brilliant writers, he proposed publishing an anthology of their stories to raise funds. “I packaged their stories into three books, one every year I was there, to raise awareness of our school and our needs,” he says. “In the eighth grade in particular, I ended up being pretty successful, and Access got a new building, which was fantastic.”

Ioffe didn’t stop there. In high school, he discovered that many of the Portland schools were overcrowded and in disrepair. A lover of architecture, he became the student representative to a committee tasked with overseeing the reconstruction of his high school as well as the group creating its master plan. Then just before his senior year, a problem with lead in the water was discovered, creating a sense of urgency to rebuild. To try to force the school board to act more quickly, Ioffe organized a student walkout. “It was the largest student walkout in Oregon history,” he says. “I led 1,500 students on a four-mile march across the city.” In the spring of his senior year, voters passed a bond to fund new school development.

But another endeavor that Ioffe started during high school has had an even greater impact, affecting students both in the U.S. and around the world. A curious youth, Ioffe tried to meet with various leaders in his community his sophomore year. “I reached out to more than 50 business and nonprofit leaders, asking for a conversation because I wanted to learn, and every single one rejected my request—except for one guy, who said, ‘Listen, I won’t talk with you individually, but if you bring 100 of your friends together, I’ll speak with all of you,’” Ioffe says. “I was like, all right!”

At first, Ioffe went to the Portland Business Alliance and proposed creating a place for business leaders and students to connect and talk, but it rejected his idea. So he decided to create a conversation series. “My goal,” he says, “was to bring students from all types of backgrounds, particularly students who didn’t have access to educational resources in business and entrepreneurship, and give them an opportunity to listen to business leaders and have a conversation with them.”

To pull this off, Ioffe needed speakers, an event space, and a crowd of students. He walked around Portland, knocking on doors and asking businesses to donate space. Eventually, he convinced the Portland Center Stage to donate its basement. Then he called and emailed business leaders until he persuaded 10 to participate. Each event would last an hour and feature one of the speakers; for 30 to 40 minutes, the speaker would answer 10 questions asked by Ioffe, with the remaining time devoted to questions from the student audience. Ioffe even got the Portland police to provide free security and the public schools to bus students who needed transportation. Local newspapers covered the events, which were a hit. “The coolest thing was there was no overhead,” says Ioffe.

About halfway through the series, Ioffe realized the model could be replicated in other parts of the country, even the world. So after each event, he reflected on what could be improved and created a manual detailing everything students would need to start their own conversation series. Thus began TILE, or Talks on Innovation, Leadership, and Entrepreneurship, a worldwide network of independent student organizations that host free conversations with interesting people in their communities.

To get other students interested in hosting a TILE event, Ioffe initially tried connecting with college counselors, but he found that didn’t work. “I realized that I had to target students who were looking for a way to learn,” says Ioffe. He started frequenting the question-and-answer website Quora, answering questions from students about innovation, leadership, and entrepreneurship. “I mentioned that if people wanted to learn more, here’s an organization, TILE,” he says. “Eventually, that proved to be incredibly successful.” By his senior year in high school, Ioffe had launched 250 chapters in 37 countries.

When applying for college, Ioffe was deciding between architecture and business schools. With TILE in full gear, he decided to come to Babson and received a Weissman Scholarship. Upon arriving, his priority was to build a team, which he did with a grant from the Helen Diller Family Foundation. “Thankfully, Babson has a lot of students that are really passionate and interested in doing something that matters,” he says. He also launched the TILE platform, an online directory that facilitates setting up TILE chapters. “You plug in where you’re located, and it gives you a list of speakers and event spaces near you,” says Ioffe. For help building the platform, Ioffe reached out to Jinn Tech, a tech consultancy founded and run by current and former Babson students.

Managing TILE and balancing school work can be challenging, but Ioffe doesn’t mind. He likes being able to talk about TILE with other entrepreneurs at Babson. “People are supportive,” he says. “A few of my friends who are at other, less entrepreneurial schools say they can’t talk about their projects because people just don’t get it.”

At the same time, Ioffe tries to remain humble about his accomplishments. “As a successful entrepreneur, you get a lot of validation, but that should never translate into arrogance or overconfidence,” he says. “When students come to TILE events and get to chat with somebody they look up to, I think the most important realization is that this person is human, you know? This person is not very different from me. And you start to realize, if this guy is head of a $125 billion company, there’s nothing stopping me from doing the same thing.”

]]>

Photo: Pat Piasecki

Beth Wynstra (left), assistant professor of English, and Global Scholar Larissa Moreira ’20

During her first semester at Babson, Larissa Moreira ’20 felt homesick as Thanksgiving break approached. “It’s a family time,” she says. “I saw everyone leaving for home, and I wanted to go home, too. But it’s too far away.”

Home for Moreira is Brazil. A Babson Global Scholar, she comes from the industrial city of Betim, located in the southeastern part of the country, some 4,600 miles from Babson Park. Luckily for Moreira, though, she also has an adopted family much closer to campus. She is a participant in the Global Scholars Host Program, which matches scholars with a staff or faculty member as a way to help students transition to life in the U.S.

Moreira was matched with Beth Wynstra, assistant professor of English. For Thanksgiving, Wynstra invited Moreira into her home, where the student shared turkey, mashed potatoes, and conversation with Wynstra’s family and friends. “I am thankful she opened her life and family to me,” says Moreira. “I really wanted to be part of a family here.”

Launched in 2014, the Global Scholars Program provides need-based scholarships for highly talented international students. Matching students with hosts began in 2015 after program directors realized that some scholars were having trouble adjusting to school and life in America. Since then, 16 matches have been made, and any Babson faculty or staff member is eligible to be a host, says Jamie Kendrioski, director of international services and multicultural education.

Participating faculty and staff are asked to stay in regular contact with their students and meet with them monthly for an activity. Boating trips, apple picking, Christmas tree shopping, and Halloween parties are examples of activities that hosts have organized, though Kendrioski says students most appreciate simple dinners in the host’s home. “That’s what students love the most, to experience U.S. home life in a relaxed family setting,” he says.

Of course, students aren’t the only ones who benefit from the program. Faculty and staff have the opportunity to form a close relationship with someone from a culture much different from their own. “I think so many of us who work in higher ed want a deeper connection to students,” Kendrioski says. “That’s why we’re here.”

Wynstra and Moreira have spent a lot of time together. They’ve visited Walden Pond, gone to restaurants and campus events, and taken in productions of The Empty Space Theater, of which Wynstra is the founding artistic director. Wynstra says that she has enjoyed learning about Brazil and hearing about Moreira’s family, but even more she is inspired by the student. Not only is Moreira making her way in a place far from home, but she also is running a venture that she co-founded. That venture, InspiraSonho (“Inspire Dream” in Portuguese), is a platform that posts scholarships, competitions, and learning opportunities for high school students. “I know being a student and keeping that business going is not easy,” Wynstra says. “She is really thriving. I am deeply inspired by her.”

The initial commitment to the host program is for a year, but many matches stay in touch beyond the program’s end. Now in her sophomore year, Moreira no longer needs as much support as she did her first year, but she and Wynstra continue to chat and get together. “We created a relationship,” Moreira says. “I really enjoy the time we spend together.”—John Crawford

]]>

Photo: Webb Chappell

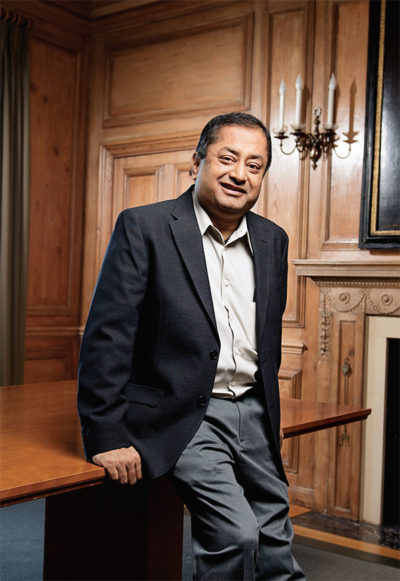

Besides his work as dean of faculty, professor Bala Iyer has had a longtime interest in information systems and strategy. “I love reading about it. I love researching about it. I love teaching about it,” he says.

When Bala Iyer decided to come to Babson in 2006, he was thinking of his daughter.

For 12 years, he had been teaching at Boston University, but a position at Babson offered the Wellesley resident a priceless benefit: It was closer to home. That meant he would have more time to spend with his daughter, Varsha, who was then in elementary school. In particular, working near home would enable him to drive her to school.

“When you want to know what’s really going on with your children, give them rides to and from school,” says the professor of information technology management. At home, Varsha typically rushed off to play, but in the car she had no distractions. She and Iyer talked and shared time together, ride after ride, year after year. “Almost every day, I would take her to and from school,” Iyer says. “That was precious to me. Time with children is fleeting.” Varsha now attends Dartmouth College, and Iyer says committing to drive her all those years was “one of the best decisions I’ve made.”

Of course, that decision also led to a rewarding career at Babson. Last year, Iyer was named the College’s new dean of faculty, making him responsible for faculty recruitment and development. “I take this as a very high honor to do this particular job,” Iyer says. “Faculty are our most treasured resource.” Among his responsibilities, he focuses on maintaining the high quality of faculty members and encouraging research that aligns with the school’s mission. He also addresses diversity and aspires to have the makeup of the faculty match that of the student population. “It is a fantastic student body,” Iyer says. “The students want the faculty to be representative of who they are.”

Iyer was nominated for the job of dean by many of his colleagues. Previously, he was chair of Babson’s Technology, Operations, and Information Management Division, where Iyer employed a collaborative leadership style. He and the division’s faculty worked closely together to give TOIM’s course offerings a much-needed revamp. “I don’t have a hierarchical style of management,” he says. “The faculty are my peers.”

When describing his role at Babson, Iyer is apt to reference the leadership style of someone far removed from academia or business: football coach Bill Belichick. Iyer is a fan of football, and of Belichick especially. He likes the coach’s system, which emphasizes the team over the individual. “It doesn’t matter who the player is,” Iyer says. “It is always about the team. It’s never about you.”

While the TOIM chair was the first leadership position Iyer has held, he has long been intrigued by the idea of managing people. Iyer grew up in Chennai (formerly known as Madras), a large, bustling city in southern India. Every evening, his family had a “debrief,” as Iyer calls it, during which they talked about their days. Iyer’s father was a manager for a government department. “He would talk about his everyday decision making,” Iyer says. “He got me interested in management. He planted the seeds way back then, when I was in my teens.” As for Iyer, he enjoyed educating his parents about various topics during these daily debriefs. “I liked explaining things. I would go on and on. They were a captive audience,” he says. “I’m sure they knew that somewhere in my future was education.”

Iyer earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering from Anna University in Chennai, and, intent on a career in higher education, he went to Louisiana State University in 1986 for a master’s degree in industrial engineering. “I was determined to be an educator,” he says.

At LSU, Iyer picked up his interest in football. Working as a math tutor for the school’s football team, he was amazed that these physically imposing athletes could be so intimidated by math problems yet excel at such a brutally challenging sport. Making small talk with players, he asked them about the rules of football and attended games. He gained an appreciation for the sport and what it can teach about success in business and life. “I have never played it, but I can identify with it,” he says. “Football is strategy for me. It’s hard work. If you want success, you’ve got to be prepared.”

Iyer next earned a Ph.D. in information systems from New York University. He immediately took to the city, with its art scene and amazing restaurants and crowds, which reminded him of the energy and clamor of his old hometown of Chennai. His love of football also continued, and he became a fan of the New York Giants. When former Giants coach Bill Parcells came north to the New England Patriots in 1993, Iyer switched loyalties to a team that still has his heart today. Iyer owns DVDs of all the Patriots’ Super Bowl victories, and as he watches them together with Varsha and his wife, Priya, Iyer offers running commentary about the players.

After graduating from NYU in 1994, Iyer went on to teach at Boston University and then Babson. While he has settled into his role as dean, Iyer remains committed to teaching and research. He has had a longtime interest in information systems and strategy, and these days he’s particularly focused on the business strategies of digital giants such as Google and Facebook. For decades, he says, the auto industry of the early 20th century served as the main model for doing business, and lessons from the industry were taught in business school. That’s changing. “The way to learn now is to look at the digital companies,” he says. “The way they run their companies is the way we’ll run our companies, regardless of industry.”

Teaching, research, and his responsibilities as dean keep Iyer’s days at Babson full but fulfilling. “I dance into work every day,” he says, “because there’s nothing else I’d rather do.”

]]>

Photo: Tony Rinaldo

Marla Capozzi, MBA’96, chair of the Babson Board of Trustees

In the fall of 2017, Marla Capozzi, MBA’96, became the first woman elected chair of the Babson Board of Trustees, joining President Kerry Healey, the first woman president of the College. A leader in McKinsey Academy, the arm of consulting giant McKinsey & Co. that helps businesses rethink their approach to employee leadership and development, Capozzi has been a member of the board since 2011. Her expertise is strategy and innovation, which she has shared with Babson in numerous ways, from mentoring to teaching to advising. Now she will use her talents to help lead Babson toward its Centennial celebration and prepare for a changing future.

What made you choose Babson for your MBA?

I was working at Lotus/IBM, and I was moving into a new position in the innovation center where I would be helping to launch new products. So I re-evaluated going to a full-time MBA program and wanted to go to the number-one school in entrepreneurship.

After graduating, how did you re-engage with Babson?

Initially, through professor Joe Weintraub’s Coaching for Leadership and Teamwork Program. At McKinsey, it’s all about coaching— our teams and our clients—and it wasn’t a skill that I felt I had mastered in my other roles. So I thought that I could give back and work on my own skills at the same time.

Who asked you to be a trustee?

Former President Len Schlesinger. When the announcement came that Len was going to be president, he had been a client of McKinsey. I hadn’t spoken to him directly, but I knew about him. So I sent him a message, and we met. He later called me and said, “If you have so many ideas about how to make Babson better, why don’t you come and help fix it? I’d like you to become a trustee.” So I thought, OK, let’s give it a shot, really having no idea what to expect.

What do you like about being a trustee?

I really enjoy governance, but more importantly the people—trustees, staff, faculty, and students—are all amazing. They just want to do the right thing and have a great impact. It’s what has kept me engaged and energized. It’s both a challenging and exciting time to be affiliated with higher education, given the disruptions in technology, the future of work, and the changing global market. But I also feel like we have a fantastic opportunity to change the world.

What does it mean to students and others to see a woman as chair?

It’s funny—at this point in time, I never thought I’d be the first woman to do anything. It seems crazy that this is still happening. But I have come to believe that it has huge meaning, given the fact that Babson was founded as a college for men, and it remained that way for about 50 years. Today, we are one of the most internationally diverse schools, and two of the last three classes were more women than men. We have our first woman president. This level of diversity of all kinds is an important message to the world about Babson and what we value.

What are some of your goals as chair?

As part of our upcoming Centennial, we need to consider the past, present, and future vision for the College. The past grounds us and gives us an opportunity to reflect. Roger Babson founded this college with the intent of teaching business leaders differently, and out of that came the creation of the discipline of entrepreneurship. He also believed that business should be rendered in service of humanity, and those strong beliefs are with us today. Now we are leaders in entrepreneurship. We need to determine the impact we want to have in the next 100 years, and how we prepare Babson for that future. We have been the first college to do many things, so as we move forward, I want to continue with this pioneering tradition. Also, as education evolves, we will have different types of learners interacting with the College in many ways, from undergraduates and graduates to online and global learners. We want every student to have a uniquely Babson experience that they can’t get anywhere else.—Donna Coco

]]>Making their third NCAA appearance in four years, the Beavers were sent to Clarkson University as part of the Potsdam Regional. They defeated Vassar College and the host Golden Knights, but then lost in the regional final to eventual national semifinalist Ithaca College.

Photo: Jeremy Viens

Abby Beecher ’19 celebrates a point with her teammates in the regional final loss to Ithaca.

Although the team’s success in the tournament was not a surprise, the actual tournament invite was, notes Neely, given that Babson had lost in five sets to Wellesley in the NEWMAC Tournament semifinals. “We were surprised to get an NCAA bid, but I think it’s a testament to the strength of our schedule,” he says. “We’ve played a vicious schedule the past few years and wanted to be in a position to earn a bid if we didn’t win the NEWMAC Tournament. We were really excited to go to the NCAAs, have a chance to start over, and redefine what our season was about.”

After enduring the long trip to upstate New York, a Babson squad that featured just four juniors and no seniors was unfazed by the moment. A victory over Vassar in the first round was followed by the thrilling five-set triumph over Clarkson, which had advanced to the national quarterfinals in four of the previous five seasons and had won 49 of its last 53 home matches before falling to the Beavers.

The team finished its season with an overall record of 22-10. And despite losing to Ithaca, the tournament run was a tremendous learning experience for everyone. “Being right there with the top teams, our confidence grew,” says Abby Beecher ’19. “We had so much fun in the match against Clarkson. We all play for matches like that, and the weekend showed us that we can compete at the highest level.” The win helped the team realize and believe in its true potential, she adds.

“I definitely saw leadership from some of our top players that we had only seen in small doses earlier,” says Neely. “They demanded excellence and responded to adversity in a super high way, and took to heart the message that you can’t take playoff opportunities for granted.”—Jeremy Viens, athletics communications director

]]>

Photo: Xueying Duanmu ’18

Painting pictures with a spray can is tricky, discovered students who attended an unconventional art workshop last semester.

The workshop focused on street art, essentially works of art, often with a message, created in public spaces. Students showing up to the studio in Trim room 215 were handed a canvas and spray cans to fill it with life and color. “I did think that it was a little unusual,” says Oussama Ouadani ’20, one of the 16 or so students who participated. “But I have grown accustomed to the cool but at times atypical events that Babson hosts.”

For sure, “cool and atypical” describes exactly the type of art events that Danielle Krcmar aims to offer to students. In recent years, the associate director of the visual arts has organized a wide mix of workshops, including explorations of mosaics, planters, drip painting, figure drawing, printmaking, and wire sculptures. Students need a creative outlet, she says, especially one that offers a tactile experience in this digital age. “I do think they crave the opportunity to make something with their hands,” Krcmar says. “It’s valuable and grounding.”

Taking time for art also can encourage a fresh perspective. “It relaxes you and opens your mind,” Krcmar says. “Sometimes when you’re focused on creative problem-solving in one area, it can trigger an answer for something else.”

Krcmar organizes about four workshops a year, and all supplies are provided, so students only need to bring their enthusiasm. In the street art workshop, artist Percy Fortini-Wright gave participants a tutorial on using spray paint—how the angle of the can, its distance from the canvas, and the pressure applied to the nozzle all produce different effects. Excited students posted images on Snapchat of their paintings in progress. Joel Mampilly ’18 was so inspired that he and some friends decided to set up their own art nights. “We bring spray paints, acrylics, watercolors, and paper and have a blast,” he says.—John Crawford

]]>

Photo: Webb Chappell

Wiljeana Glover, assistant professor of technology and operations management

When Wiljeana Glover was in college, a beloved aunt died due to a medical error. That tragedy led Glover to start thinking about health-care operations, an area that would become a focus of her career. Today, Glover is an assistant professor of technology and operations management and the faculty director of Babson’s Schlesinger Fund for Global Healthcare Entrepreneurship, a multifaceted initiative involved in research, student programs, and educational activities.

In addition to her efforts in health care, she also fills her days with praise and music. A singer and songwriter, Glover enjoys serving as the director of worship and arts at her church, Pentecostal Tabernacle, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

You’re originally from Georgia. What do you like about Massachusetts?

My husband is a psychologist, and we jokingly call Boston the mecca of all things health care. So I think me being a health-care researcher, him being in the field, you can’t really be in a better location to learn and be challenged and be innovative. We love it.

Can you describe your research?

I study health-care systems and the intersection of operational strategies and the human perceptions of how well those operational strategies are going. When a hospital decides to try a new business model or approach to operations, I’m interested in how does that align or not align with the culture of the organization. What are the human implications? Are people excited about this, do they feel empowered by it, or do they feel limited by it?

Your work looks at integrating care. What does that mean?

I think in part I’m influenced by what happened to my aunt, a situation where one care provider had a piece of information that her surgeon didn’t have. That started me thinking about how you better coordinate care. How do you coordinate all of the players, all of the departments that need to be involved?

Medicine may be a big part of your life, but so is music.

A lot of faculty members here have an artistic or creative side. My creativity has always been in music. There are recordings of me making up songs when I was 3. And so I’ve always been a songwriter and a singer, and that’s something that I am blessed to be able to do at my church.

Tell me about your church.

I love that my church is extremely diverse. It’s a really eclectic mix of people, which forces you to think about life and faith in a very different way because everyone is coming from a different cultural background. We have a lively service. Lots of clapping, lots of singing along. A local reporter came to a service, and she said she could feel the ground moving under her feet.—John Crawford

Photo: Webb Chappell

Babson President Kerry Healey

During the past several years, Babson’s incoming undergraduates have been increasingly and intentionally diverse. The Class of 2021 is 52 percent women, 28 percent international, 44 percent U.S. students of color, and 28 percent historically underrepresented minorities. It also is the most competitive and well-qualified class in Babson history.

Diversity of all kinds extends to socioeconomic circumstances, and we are working to ensure that a Babson education is accessible to exceptional students regardless of financial means. This year, we awarded $37 million in institutional grants and scholarships. The Class of 2021 includes 14 percent Pell Grant recipients, a percentage we hope to increase in coming years. And, for the first time in nearly two decades, Babson met 100 percent of need for incoming domestic students.

Among those granted scholarships is a group of Diversity Leadership Award recipients selected for their potential to lead and foster an inclusive community at Babson. Next fall, the planned cohort will include public school students from Babson’s Hub locations of Boston, San Francisco, and Miami. As part of our vision to make Entrepreneurial Thought & Action accessible to everyone, everywhere, we have established small-footprint, high-impact Hubs in these communities, known for their entrepreneurship ecosystems, and we are pleased to extend these awards to local students.

It is important that we work to make historically exclusive environments—such as higher education—welcoming to all students, including those from communities where college attendance might not be the norm. Everywhere, in every situation, there are aspiring leaders with the potential to change the world for the better.

Our campus is enriched by varied perspectives and experiences, and our global network of 40,000 alumni and friends in 114 countries is equally dynamic. We are taking steps to ensure that Babson’s governance boards also are representative of all backgrounds and recently elected the first chairwoman of the Board of Trustees, Marla Capozzi, MBA’96.

I am reminded of the words that Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, H’17, former president of Liberia, shared at our 2017 Commencement exercises, in which she beautifully articulated the inherent inclusiveness of entrepreneurial leadership: “At a time when many around the world are looking to build walls, close doors, and limit interactions across cultures, the entrepreneur, by his or her own definition, is a bridge builder. A door opener. A problem solver. I salute you, the next generation of innovators and bridge builders.”

Kerry Healey

]]>Her younger sister, Tina, often wanted to spend the night in Maja’s room. Maja would let her come in, but only on one condition, that the pair would spend time discussing their plans for the future. So Tina would drag her mattress into the room, and night after night, the sisters talked of ideas and aspirations, of the ventures they would start, of how they would change the world. Maja loved these talks, and so did Tina, even if she was pushed into them by her older sister.

Then at the age of 15, Maja met someone with a similar spirit at her high school. They bonded over a multitude of sports, from skiing to hiking to roller blading, but they also shared something deeper. “What really brought us together was that we liked to dream together,” Maja says. “He was the best person to dream with.”

That person was Mihael Mikek, MBA’06. The two became high school sweethearts and then attended the same college, the University of Ljubljana, located in Slovenia’s charming capital. In each other, they found a partner for adventure, romance, and turning dreams into reality. “Our values, about life and what is worth fighting for, about what is right and wrong, about adventure and dreaming big, that stuff is very much aligned,” says Mihael, who goes by Miha.

Leaving Slovenia, Maja and Miha set off to find what life had in store for them. They came to Babson, settled in Boston, and started a family, not to mention a successful business. That business, Celtra, offers a creative management platform for digital advertising. Miha serves as the company’s CEO and Maja as its CFO. With prescient timing, Celtra was launched in the early days of smartphones and since then has ridden a wave of growth. Two-thirds of Fortune 500 companies, according to Celtra, use mobile ads created with its platform. Last year, Celtra’s platform delivered more than 90 billion ads to mobile internet and apps users.

As they build their business, as well as raise two small children, the Mikeks dash through days that are filled to the brim. But for the two dreamers from a small country, who were hungry to one day “live our own movie,” as Miha puts it, this chock-full life is what they were seeking. “It’s about freedom, independence, doing things on our own terms,” Miha says. “It’s exactly how we wanted to live our lives.”

Spouse and Co-Worker

Celtra’s Boston headquarters is located on Boylston Street, on the 11th floor of a Copley Square office building. Looking out on Back Bay and the Charles River beyond, the office’s windows offer a panoramic view of the couple’s adopted hometown, from Kenmore Square’s Citgo sign to the Zakim Bridge.

On a Monday afternoon at 12:30, Miha darts out of his office, which is simply decorated save for a quote about business strategy and vision written large on the wall. As he makes a beeline for the conference room, he passes Maja’s office, which sits next to his and is filled with pictures of family and friends, and taps on the glass. It’s time for a weekly management meeting, in which the Boston office checks in with Celtra locations around the world. The company has 180-plus employees, with about 70, the bulk of them engineers, stationed in its largest office in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Celtra also has locations in London, New York, San Francisco, Sydney, and Singapore.

In the conference room, Miha and Maja sit directly across from each other. Miha leads the meeting, while Maja chimes in when needed. They speak fast and to the point as leaders from various Celtra offices appear on a large video screen on the wall. “Do we have London on?” asks Miha, who proceeds to run through the numerous deals that Celtra is lining up with large companies looking to improve the effectiveness of their mobile advertising. “Let’s push these things forward,” Miha says.

In Celtra’s Boston location, Maja and Miha Mikek have adjoining offices.

Among those sitting in the meeting is Dekyi Lhaze, vice president and controller of Celtra. During her five years at the company, Lhaze has had ample time to witness the Mikeks interacting with each other. For some, the idea of starting a business with a spouse, of having the personal and professional so closely intertwined, would make the challenges of entrepreneurship even more complicated. But Lhaze sees the Mikeks as a steady hand who set a good example for their employees. “They have a very honest relationship,” Lhaze says. “They tell us if we’ve messed up, and they will tell each other if they’ve messed up, even in front of others. It doesn’t matter to them if we’re listening. They are true and honest. They feed off of each other.”

Rodney Alvarez, Celtra’s vice president of talent management, admits to having been curious, and a little concerned, about the dynamics of working for a married couple when he started at the company two years ago. Those concerns proved unfounded. “They are great together,” says Alvarez. “They are a well-synced team. They don’t bring any drama.”

Miha acknowledges that starting a business with a spouse blurs the line between work and home, but that doesn’t bother him. He enjoys sharing his workday with Maja and encourages other entrepreneurial couples to do the same. “This is our life,” he says. “There is no work-life balance. An important part of life is work, another is family. You can’t separate these things. I cannot imagine it otherwise.” In the mornings, Maja and Miha walk to work from their home in the nearby Boston neighborhood of Beacon Hill, and they often bring their children, 6-year-old Sofia and 3-year-old Lev, into the office before school starts. In the evenings, the whole family spends time together, and once the children are asleep, the Mikeks work on the business some more, with night-owl Miha staying up till 2 or 3 a.m.

In the office, the couple bring complementary skill sets. “We are very different in terms of our strengths,” says Miha. Proficient at organizing and connecting with people, Maja focuses on creating a positive culture in the company and tries to get to know every employee. “She takes a holistic look at people,” says Megan St. Ledger, Celtra’s senior legal counsel. “She is interested in people, and I think that is unusual in that role.” Indeed, the CFO has long talked of becoming a social worker one day. “A lot of CFOs look at a company through raw numbers,” Maja says. “I look at it through the people we have.”

Every Monday, Maja and Miha Mikek meet via video conference call with the company’s multiple locations around the world.

Miha, on the other hand, focuses on pushing Celtra forward. “He demands a lot, challenges everything, and pushes to the limits, many times wanting the impossible,” says Gregor Smrekar, Celtra’s COO. “But then it is OK because he is even harder on himself, and because the goal is big and worthy.” A voracious learner, Miha strives to understand where the ad tech industry is headed and to visualize Celtra’s place in it, says Maja. He always is reading and reaching out to people who can provide insight. He feels no need to be the most knowledgeable person in the room. “He loves to surround himself with smarter people,” says Maja. “He is not ashamed to be the underdog.”

It Felt Right