Elizabeth Shea ’13 and dad, Michael

The 25,000-plus athletes run 26.2 miles for many reasons—to compete, to have fun, to fundraise, to honor a loved one. But this year, on April 15, the events that unfolded were different and difficult to comprehend. The weather was close to perfect, and everything went well until 2:50 that afternoon when the first of two bombs exploded near the finish line. This was the first marathon for Shea, who ran along with her father, Michael, as a member of the Mass General Marathon Team. When she was 10, she had been treated for histiocytosis in the hospital’s pediatric hematology/oncology ward. Shea’s fundraising efforts for pediatric cancer research were successful, but the race was cut short at mile 25.5 for her and her dad. About 3,000 runners were in their immediate area, and news started to leak from those with cell phones. “It was scary, because no one knew if there were more bombs,” Shea remembers. “I thought about people who live in fear like that all the time. I may never understand that, but I experienced it for one and a half hours.”

Jason Jacobs, MBA’05

The race always has held a special place in the heart of veteran runner Jason Jacobs, MBA’05. As founder and CEO of RunKeeper, he ran one year dressed as a smartphone to promote his business, which offers a personal training app. This year Jacobs could see the finish line when he heard the first explosion. “When the second bomb went off, I saw the fireball,” he says. Worried that there might be more, he made his way to the grandstands to look for his wife and their 1-year-old child, who had been there to watch him finish. Frantic moments followed until he heard they were safe.

Jacky Mozzicato ’10 was on her third Boston Marathon as a member of the Dana-Farber Marathon Challenge team. Mozzicato, who exceeded her goal of raising $10,000 to celebrate her 10th year of being cancer-free, runs for the hospital that treated her. Toward the end of the race, Babson friend Joscelyn Chang ’09 hopped in so they could finish together, but their immediate cohort of runners was stopped at mile 24. “There was mass confusion,” says Mozzicato. “I asked a police officer what happened, but he didn’t know. The uncertainty made me feel sick.”

Jacky Mozzicato ’10 and Mark Donnellan ’09

Fellow Dana-Farber team member and a friend of Mozzicato from their Babson days, Mark Donnellan ’09 finished his first marathon in 3:59:27, which brought him in about five minutes before the explosions. He was being treated for dehydration in the medical tent when the bombs exploded. Donnellan was impressed with the medical team, which had not trained for such a large-scale disaster. “The tent quickly became a triage area,” he says, “and the staff remained focused and courageous in spite of the chaos.”

Sara Wojda ’14, another Dana-Farber team member and first-time marathon runner, crossed the finish line in 4:01:36, just one minute before the first explosion. “The noise of the second explosion created panic,” she says. “I cut down a side street to get out of the area, but my legs were so bad I could barely walk.” Wojda knew she needed water, so she returned to the water station near the finish line. The area, which should have been full of volunteers and exhausted runners, was completely deserted.

Sara Wojda ’14

After Wojda connected with her parents, who had seen her run by earlier, the trio walked to their Boston home. As she watched the news, the day felt surreal. “What if my run had taken a minute longer?” she says. “I could have been right there.”

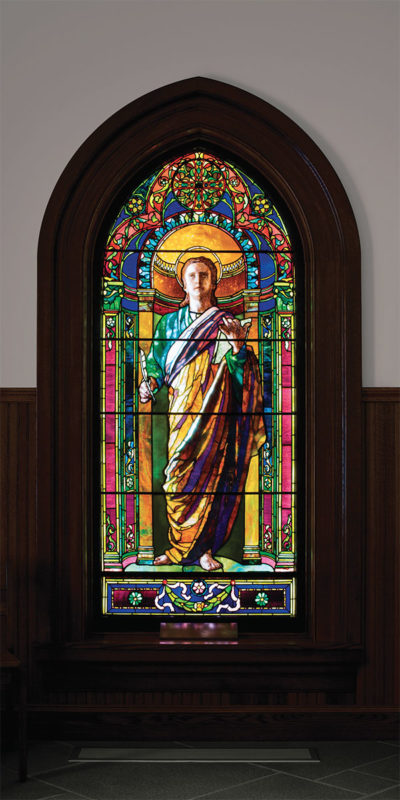

But Wojda won’t let the tragedy cloud her vision of the race, a sentiment shared with the other Babson runners. She’s adamant about running again. “No way that I wouldn’t,” she says. On May 1, she spoke at a memorial ceremony for the victims held in the Glavin Family Chapel. Toward the end of her talk she said, “It’s not about what we haven’t done, what’s in the past, but it’s about what we can do.”

Mozzicato agrees. “I run for a bigger cause than just a marathon. I hope to run for Dana-Farber again. Next year may be even more passionate.”—Sharman Andersen

]]>

Photo: Webb Chappell

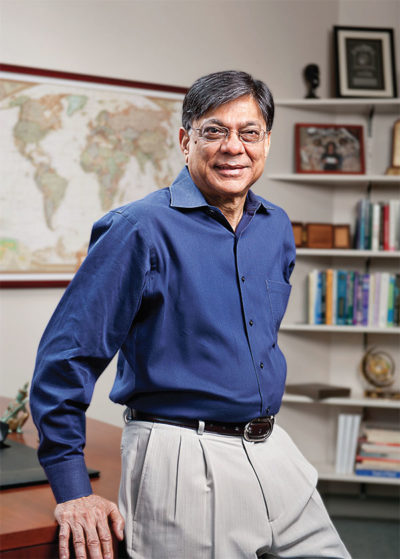

Shahid Ansari, CEO, Babson Global

How is your role at Babson Global going to change?

Quite honestly, nothing will change other than the workload, which will become a lot less now that I don’t have to carry on the duties of provost and tend to Babson Global. During the last few years, Babson Global was what we call a lean startup. It did not receive any funding from the College and all activities were financed from resources we generated. Now that we are on the verge of perhaps working with the Saudi Arabia Ministry of Economy and Planning to create a new business school, it’s clear that I will no longer be able to hold down two jobs, running an existing college as well as creating a new one. So the time was right to split my job into two separate jobs.

Tell us some more about the Saudi Arabia project.

The important point is we are not creating a branch campus. Our desire is to build something for them, help them to operate it for a few years, transfer full control back to them, and then help them sustain that excellence over time. We are using what we call a Build, Operate, Transfer, Sustain model. We added the sustainability piece because we recognize that it’s important to be connected to the institution after we leave. After we leave, the excellence is hard to sustain. So we are trying to find a mechanism by which we could have a continuing engagement with our partner schools so they don’t decline over time.

How does Babson benefit from all of this?

First of all, there are reputational benefits. We have seen an increase in the number of applicants from around the world. So that’s on the student side.

In many cultures now we are regarded as a serious player in the field of entrepreneurship. We are represented in forums that we weren’t represented in before, such as the World Economic Forum. We have been invited to entrepreneurship summits that are hosted by the State Department, by the White House, by the USAID. We have requests now for help from countries that were never on our radar, like Brunei, Bahrain, China.

We have had financial benefits. The last few years we have had direct contributions of a couple of million dollars into the College. In addition we have provided close to $4 million in income to our faculty because of the opportunities to work on Babson Global projects.

But in my opinion, apart from all of that, the biggest benefit is the chance to learn. As we have designed things for others, we have learned a lot ourselves. This work has provided Babson with a live lab worldwide to try out things and, if they work, bring them back to us. It’s informing our curriculum design and our organizational design.—Donna Coco

]]>Many cities are still figuring out how to deal with the growing popularity of food trucks. By no means a new idea, the business of selling street food dates all the way to ancient times. But in 2008, gourmet trucks such as Kogi in Los Angeles, which sells Korean BBQ, brought an unexpected flair—and, thus, popularity—to the cuisine. Seeing that success, more trucks have tried to capitalize on the increased interest in foodie street fare. How far have food trucks come since their roach-coach days of selling prepackaged sandwiches at construction sites? An industry report pegged the mobile food business at $1.5 billion in 2012. Even restaurant-guide Zagat now rates food trucks in certain cities.

“Serving food to people is a calling of the highest order, and I don’t say that with any sense of irony at all,” says Andrew Zimmern, entrepreneur in residence at Babson. Zimmern, a multifaceted entrepreneur perhaps best known as the creator, host, and producer of The Travel Channel’s Bizarre Foods, began his career as a chef in the ’80s. Wanting to get back to his cooking roots, he started a food truck called AZ Canteen in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area at the end of last summer.

Zimmern offers the following advice to those interested in the food truck business. “Be prepared. It’s life changing,” he says. “Everyone eats. Everyone thinks they’ve figured it out more than anyone else. Nobody turns to a family member at the dinner table and says, ‘You know what? I’m going to open my own accounting practice.’ Everyone says, ‘Honey, you make the best pork chops in the world. We’re going to open a pork chop shop.’ I think it’s because of our special relationship with food. But you have to be very dedicated. It’s not easy.”

Inspiration from the Big Apple

With two trucks and a little more than one year of experience under their belts, The Chicken & Rice Guys—which include So and Jaemin Lee ’08—know how tough the food truck business can be. If the weather is decent, their trucks are out six days a week year-round. Prep starts about 9 a.m., and then the trucks are off to the first location for the 11 to 3 lunch shift. Next they’re off to another location for the 4 to 8 dinner shift. After dinner comes breakdown, with the day wrapping up around 9 or 10 p.m. That’s just the service side of the business. Cooking, shopping, accounting, promoting—all these tasks and more need taking care of as well. “I did not personally expect this much work,” says Lee. “I don’t think Ian did either.”

Business has been good, though, so So and Lee don’t complain. Just how two business-school grads became owners of a food truck operation relates back to So’s hometown roots in New York City. Wanting to start a business together, So, Lee, and So’s high-school friend, Kevin Lau, already had been meeting weekly to toss around ideas. Then one weekend while visiting his parents, So heard about a popular food cart that sells chicken and rice, so he went and tried the food. “The Halal Guys are super popular. They have lines down the block,” he says. “I saw the hype and thought we could bring the food to Boston.”

Next meeting, he proposed the idea to Lee and Lau. Says Lee, “It’s kind of funny, because MIS [management information systems] is my background, and Ian wanted to do something more fancy like IT consulting, and then all of a sudden one day he comes and says we have to do this chicken and rice cart. I was like, what? Do you really want to do street food?” But after a trip to taste the food, Lee was onboard, as was Lau. Jenny Giang, So’s girlfriend, joined soon after as the fourth partner.

With no food experience, the group faced the not-so-easy task of figuring out how to replicate The Halal Guys’ dishes, which include chicken or lamb served on a bed of rice with shredded lettuce, pita, and sauces—white (tangy garlic) and hot—for garnishing. Both So and Lau, also a New York City native, would travel home and buy meals for taste tests. “I asked my mom to taste it first,” says So, “and right off the bat she got a few of the main ingredients.” They would have friends who are fans of the cart try their dishes, and they would bring the sauces back to Boston for more deciphering by the group. “We discovered the best way to figure it out is actually to smell it,” says So. Many nights and recipes later, they came up with what they considered the winning combinations, and even expanded the sauces to include BBQ and two versions of spicy.

Photo: Tom Kates

Ian So (left) and Jaemin Lee (right) brought flavors from a famous food cart in New York City to the Boston area with their food trucks. Customers especially love their sauces, they say. To let people know the daily locations of their two trucks, they use their website, Twitter, and Facebook.

Initially, the group bought a cart, similar to what they had seen in New York City. But they soon discovered that the permit to operate a cart was difficult to obtain. “For carts, you can only sell on private property, so you’ve got to find somebody willing to let you sell on their property,” says So, “and most of the good spots are taken. It’s a very old industry.” Boston, however, had started a new food truck program in 2011, and with the city interested in growing the program, getting a permit was relatively easy.

Acquiring a food truck proved more interesting. After deciding to go with a used truck, So searched the Web and discovered one on eBay in Miami. The catch: They had to buy it that weekend. They called the owner, asked him questions, and talked to his mechanic. “His mechanic said everything checked out,” says So, “and we just had to go on our gut that nobody was trying to cheat us.”

So and Lau purchased two one-way tickets and arrived about noon on Saturday. They checked out the truck, which seemed fine, and headed for the bank. “We took out $19,000 and paid him in cash. That was really scary,” says So. “Driving it home was crazy. Kevin drove it first, and he was driving really slow. I was leading with the rental car, and I was like why is he all the way back there? We were driving in the wrong gear for about 20 minutes.” They drove home in 25 hours, taking turns sleeping on the floor of the truck.

With their truck in place, the group now had to find a place to prepare their food. City regulations don’t allow for preparing food at home, so a search for commercial kitchen space commenced. “That was a whole can of worms,” says So. “In the beginning, it was one of our biggest challenges.” To find a spot, they would search on Google, call people, ask for referrals, network, and then show up and try to get the space. “A lot of these kitchens, if something goes wrong, they’re liable, so their business will be impacted, too,” says So. “Some people are charging high fees. Some people won’t let you in at certain times. Our kitchen now—we share our kitchen with seven other trucks—is the most stable location we’ve been in, but we’ve had to switch kitchens about four times.”

Photo: Tom Kates

Despite the hurdles, The Chicken & Rice Guys launched in April 2012, originally just on the weekends but quickly switching to full time, six days a week. “There was no way we could break even if we were just doing weekends,” says Lee. At this point, So and Lau quit their regular jobs to work exclusively on the business. Lee still has his job as an information systems analyst, but he works weekends, doing the shopping and helping prepare and cook food (he usually makes the sauces), and he helps out during the week when needed.

The group also launched another truck in the winter of this year. Winters, as one might imagine, are tough. After one storm, So had to shovel out a space before the truck could set up for lunch. “We do OK,” he says, “but it’s about half the business.” A bad weather day, regardless of the season, affects business, but their catering business is beginning to pick up, says So, which helps. Future plans include a potential brick-and-mortar restaurant, consulting, even franchising. “I think the food truck industry is plateauing, so to really take this business further, we can’t just be a food truck,” he says.

As surprising as their leap into the food truck world may have been, So and Lee enjoy running their own business. “It’s so fun to see the business grow,” says So. “I love record sales, like how much we can sell in one day. It’s exciting.” And even though Lee doesn’t put in many hours on the truck these days, he likes working with friends and meeting people. “When people like what we do or thank us or recognize our efforts,” says Lee, “it’s worth the hard work.”

Learning on the job

Photo: Steve Henke

An experienced chef, Andrew Zimmern created the recipes for the adventurous dishes—including goat burgers and sausages—his truck serves.

Most weekdays, the AZ Canteen truck starts cruising the streets of downtown Minneapolis around 9 a.m. The city has designated a three-block area for food trucks to set up, and those blocks are jammed with back-to-back trucks offering all kinds of fare. No one, however, can park even a minute before 9. “We parked at 8:58 this morning and were told to move,” says Mateo Mackbee, truck manager and chef for AZ Canteen.

The truck typically doesn’t start serving until around 11 a.m., but the number of people who come make the two-hour wait worthwhile. During lunchtime, the broad city sidewalk becomes packed with people wanting to eat AZ Canteen’s unusual offerings: goat burgers and sausages; grilled veal tongue; andouille, oyster, and crab gumbo, to name a few. Zimmern has brought some of the flavors he has discovered while traveling the world to his hometown.

He chose to start with a food truck versus a restaurant because of costs. “It’s cheaper, more fun, and the most important reason was the flexibility,” he says. Making changes, whether to the menu or location, is easy. Because the food truck industry is strong in Minneapolis, Zimmern checked out what other trucks were offering to see what niche he could fill. But he also didn’t let what he discovered affect his decisions too much. “You have to do your due diligence and understand the marketplace,” he says. “But then there’s the art part of it, which is what do you want to make as a chef and an owner. The mix of art and commerce, I think, is always the toughest thing in the food business to figure out.”

Zimmern also sees his truck as an extension of his brand. People watch him on television, read his articles in publications, go to his websites, listen to his podcasts. “But they couldn’t eat my food,” he says. “I had some friends saying let’s do this, so we signed a partnership agreement and off we went. That was really fast and easy. The tough part now is drilling it down and making it work as a business. That’s ongoing.”

Photo: Steve Henke

Andrew Zimmern

Photo: Madeleine Hill

Years of experience in the food industry didn’t prevent Zimmern from making mistakes. The truck got off to a great start, he says, capturing a strong following for the four to five weeks it operated during its inaugural summer and then acquiring kudos and national buzz at a food festival in New York City. To escape the cold Minnesota winter, the truck then went to Miami. “Huge mistake,” he says.

Turns out the food truck culture in Miami is mainly weekend rallies. “We thought, ‘We’ll drive around. We’ll find a place.’ But you find a place that works legally, and then no one stops by because it’s not in their culture to grab something off a truck,” says Zimmern. “We ended up hemorrhaging money, which would have buried a lot of different companies. We couldn’t get the truck back up here fast enough.”

So one of Zimmern’s big decisions for next winter will be what to do with the truck. For now, however, he’s focusing on the current season. He has opened a brick-and-mortar version of AZ Canteen at Target Field, home to the Minnesota Twins baseball team, and plans to expand to more ballparks and sports stadiums. A second truck is possible, too, depending on how the catering side of the business progresses and whether Minneapolis and St. Paul expand the number of places that food trucks are allowed to go. Right now the rules are too limiting, says Zimmern, packing the trucks together in the downtown area and not allowing for uptown parking near the lake and nighttime foot traffic.

Like the question of where to go when the weather turns cold, Zimmern is confident his team will figure it out. “I mean, that’s the thrill of it,” he says. “It’s like doing a crossword puzzle. At a certain point you know you can fill in those last 30 squares. We’re almost there.”

From Beantown to Portland

One day Jack Barber ’15 was chatting with his parents in a coffee shop in Boston. They were talking about the city, and Barber told them about its popular food truck scene. He wondered why Portland, Maine, the city near his hometown of Cape Elizabeth, didn’t have such offerings, to which his father answered, “I don’t know.” Barber replied, “Let’s open up a food truck.” He texted that message to longtime friend Ben Berman, who attends Tufts University, located right outside of Boston. Berman loved the idea. The two wrote a business proposal for a food truck offering gourmet burgers, and with backing from friends and family, decided to launch their business in the summer of 2012 after school released (they were still first-years at the time).

Photo: Patrick Piasecki

Family cookouts inspired the menu for Mainely Burgers, the original business of Jack Barber.

One big problem, though. Portland didn’t allow food trucks. Not to be dissuaded, the friends began searching for a place to park. A family friend suggested Scarborough Beach, a scenic state park not far from downtown Portland. “It had a concession stand, but we thought it could be improved,” says Barber. “We wrote them a proposal saying we’re going to bring in gourmet burgers, good hot dogs—everything’s fresh. They were all for it.”

With a place to operate, Mainely Burgers was in business. Now Barber and Berman had to pull it all together. They ordered a custom-built trailer from Concession Nation in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., because it was roughly half the price of a truck. To develop a menu, the two texted each other burger ideas. Their popular Mainah, which includes cheddar, bacon, sauteed onions, sliced green apples, and maple mayo, came from these texts. Obtaining permits, finding local distributors and suppliers, hiring help, and learning how to drive and park a trailer were on their to-do lists as well.

Come June, though, they were ready to go. That summer they parked the trailer at Barber’s house during off-hours. “My parents were a little upset when they heard the bread guy coming in at 6 in the morning,” says Barber. Deliveries aside, a typical day began around 7:30 a.m. They would drive the trailer to the beach, park and unhitch, hook up to water and electricity, and begin prep. Service started around 10 and would end around 5, followed by cleanup and, sometimes, a catering gig, which helped offset costs when the weather turned bad. Some evenings they squeezed in paperwork. They did this seven days a week.

At first, figuring out how much food to order for inventory proved challenging. “We ran out a couple of times,” says Barber. “Then by July and August, we knew through checking receipts and knowing the weather how much we were going to need for each day. At the end of the summer, we barely had any inventory left.”

Photo: Patrick Piasecki

Mainely Burgers started with a trailer at Scarborough Beach.

Business that summer was “awesome,” says Barber. But the two still wanted a food truck. “Our goal was to be in Portland from the start,” he says. So while operating their summer business, the two joined a food truck initiative to convince the city to allow the vehicles. “There were a lot of restaurants coming to the town hall saying this is going to take away business,” says Barber. “What we had to say to them was it’s a different market. If someone really wants to take the time to enjoy a great lunch or dinner, they’re going to do that. If someone wants a quick bite but wants gourmet, they’re going to come to us.”

The food truck laws passed. So this summer, Barber and Berman expanded. They bought a food truck for lunch service as well as catering and events. They renewed with Scarborough Beach for the summer and will keep the trailer parked there for the season. And, most recently, they bought a used ice cream truck, refurbished it, and opened in July as Mainely Treats, offering handmade ice cream sandwiches, root beer floats, and sundaes.

Photo: Patrick Piasecki

Not that Mainely Burgers didn’t encounter any snags. Even though Portland now allows food trucks, the spots designated to them don’t have enough foot traffic, says Barber, so they aren’t financially feasible. Instead, he worked a deal with a private lot, which a provision in the laws sanctions as long as the truck is at least 65 feet away from any restaurant. The spot, near the courthouse in downtown Portland, draws decent traffic, but still doesn’t command the crowds the two would like. As such, Barber and Berman decided to turn the commercial space they rent in the outskirts of Portland—where they keep an office, park the trucks at night, store supplies, and receive deliveries—into another service location. They’ve set up picnic tables for people who would prefer to sit and eat rather than take their lunch to go, and they’re thinking about staying open for dinner as well. “We’ll still occasionally go to the other location, but we’re hoping to make this a destination,” says Barber.

Next up for the pair is extending the season for their operation to include spring and fall, not a huge deal, except both Barber and Berman will be in school. But Barber says they found people who they can trust to run the trucks, and he and Berman will still be involved, albeit remotely. Business has been strong, so it’s worth the potential risk. “We’re excited for what is to come,” he says.

Extending their brand

Photo: Chris Giles

While working on a project for a class his senior year at Babson, Eric Adler came up with the idea for a Mexican restaurant that offers high-quality, casual food. The idea stuck with him, and years later he opened his restaurant and food truck business.

Eric Adler ’06 originally wanted to launch his food truck while developing and building the restaurant he co-owns, Puesto Mexican Street Food in La Jolla, Calif. But he and his partners (brother Alan, cousin Isi Lombrozo, and chef Luisteen Gonzalez) ran into problems finding commercial space to prepare their food, so they decided to wait until the brick-and-mortar eatery opened in early 2012, and then began looking for a food truck about 10 months later. The truck hit the road this January.

Puesto uses its food truck mainly for catering and events. Although a curbside food truck business exists in San Diego, many trucks focus on private events, says Adler. “If we were to just show up somewhere, we wouldn’t do very well.” Puesto has been invited to sell at San Diego Padres baseball games (the president of the Padres is a fan of the restaurant, says Adler). Craft breweries are popular in San Diego County as well, he adds, and often invite food trucks like Puesto’s to sell food in their parking lots for the day.

After checking out food trucks in the popular Los Angeles scene, Adler says they bought their truck from a man in San Diego who was giving up on the business. “We found it searching on Google,” he says, “and then refurbished it.” Adler called on a design firm he had worked with previously in Washington, D.C., to create their logo and the look for the truck. Doing a completely custom truck would have taken too long, he says. “In Los Angeles, I saw this one truck that was more intense and larger than some restaurants. One guy told me there’s over a year waiting list to get one of those.”

Puesto, however, doesn’t need anything that decked out. They do all their prep and cooking at the restaurant. Making everything from scratch, from the salsa and guacamole to fresh tortillas, is easier with their own space. The truck offers a scaled-back version of the restaurant’s menu: three or four types of tacos; a Mexican fruit and veggie cup seasoned with chili, lime, and sea salt; and drinks. “We try to keep it simple, because even though we’re cooking in the restaurant, we’re still preparing everything on the trucks,” says Adler, “and we don’t want service to be slow.”

Photo: Chris Giles

Eric Adler ’06

In sunny San Diego, weather isn’t much of a problem. When it does rain, however, no one wants to drive the truck, says Adler. “Driving these things is really tough. They’re like UPS trucks. It’s a big box. When it rains, our employees who drive it get freaked out,” he says. “We have vans, too, and those things feel like Ferraris compared to the truck.”

Photo: Chris Giles

All dishes are made from scratch, such as the popular Mexican Street Cup.

Besides increasing revenue, Puesto’s truck has been great for its brand and gives the business flexibility, says Adler. “People want to hire the truck,” he says. “When you’re out there at festivals and events, it’s really cool. We like being able to take our tacos to people and not just be in one market.”

The food business is tough, says Adler, but Puesto has been doing well and is building another restaurant in downtown San Diego. “There are a lot of businesses where you don’t know much and can go in and scale up your experience as you go. But in the food business, as soon as you open the door, you’re bombarded,” he says. “Customers are spending their money and eating. You learn immediately what they like and don’t like. It changes and evolves fast. There’s no time for mistakes. But it’s fun, too, working with a lot of different people. It’s really a great business.”

]]>

Photo: Webb Chappell

Sebastian Fixson

That optimism also stems from Fixson’s passion for design and innovation. The world may have many problems, he says, but designers dream and tinker to figure out how to solve them. A better way—that’s what designers seek. “I think designers are inherently optimists,” he says. “A designer wants to create solutions to improve lives.”

A researcher of new product development, Fixson teaches two product design classes, one for undergrads and one for grads, but admits that he didn’t always plan to become a professor. Born and raised in Germany, Fixson was inspired by American higher education when he came to MIT for his PhD. Interactions between professors and students were far more collaborative than what he had seen in Germany, so much so that he scrapped his original plan, which was to work in industry after graduation, and entered academia. After teaching stints at University of Michigan, MIT, and Northeastern University, he came to Babson in 2008.

Fixson thinks a lot about what makes for good design. “It doesn’t have to be fancy or complicated,” he says. Ask him for examples, and he’ll rave about a unique teaspoon from an Italian product design company and pull up its image on his computer, showing how the spoon’s hollow handle can drain a tea bag. He’ll also point to the sleek desk lamp in his Tomasso Hall office. Most of us don’t dwell on the fine details of desk lamps, but Fixson picked his based on various criteria. He likes how the lamp shines brightly and broadly despite its narrow design, and he also likes how it uses LED bulbs, which are long lasting and energy efficient. For him, the lamp is a nice mix of form and function.

Like many, Fixson also admires the simplicity of Apple products. Remember the first time you used an iPod and its click wheel to scroll through your music? Remember how easy and right it seemed, how natural? “One of the reasons Apple products are so successful is they’re intuitive,” he says.

Fixson covers a lot of ground in his product design classes. In just three months, he takes students through the design process, from identifying a problem or opportunity, to generating ideas to address it, to prototyping. In last year’s MBA product design course, student teams created a dog toy, biodegradable urn, women’s shoe with adjustable heel, and a kit for home brewers to clean their beer bottles.

“What the classes teach is the design process itself, which is useful for any innovation project, be it in a new venture, an existing company, or a nonprofit,” Fixson says. “It gives students an appreciation of how to create anything.” Indeed, the flexibility and potency of this process is shown in another Fixson class, “Social Entrepreneurship by Design,” in which students use the design process to create services addressing social issues.

Fixson teaches his design courses in Olin 125, otherwise known as the Romper Room. The room is stocked with arts and crafts supplies that wouldn’t be out of place in a grade school classroom. There are markers, Popsicle sticks, pipe cleaners, tape, and lots of Play-Doh. He keeps cans of the putty in his office, too. “Once people have it in their hands, they want to play around with it and think about ideas,” he says. Concepts that students have percolating in their heads can be fuzzy and hard to articulate, so they can use the art supplies to create rough models of their thoughts. “They’re not meant to look perfect, or even look real,” he says. “They’re meant to convey an idea.”

Good design, though, involves more than just playing with Play-Doh. In his office, Fixson keeps a list taped to the wall of the qualities that are invaluable for the design process: empathy, integrative thinking, experimentation, collaboration, and, not surprisingly, optimism. Of these, empathy is particularly important and something he stresses to students. As they create products, designers must become almost psychoanalysts to understand the lives and concerns of those they’re trying to help. “All organizations have an increasing need to innovate in order to survive,” he says. “The success of any product or service hinges on whether it matches the user’s needs. And the only way to find this match is to invest time and attention to understand users.”

As an example, he points to the work of a design firm creating a new insulin pump for diabetics. The designers focused on the feelings of the children using the old treatment, which was cumbersome and impossible to hide. “Think about what it means to a kid,” Fixson says. “It suggests to the world you’re different.” The end result was a much smaller and less intrusive device. To Fixson, this is what good design is all about. “I find that very satisfying,” he says.

]]>What people may not know is that Healey, coming from a struggling public school system, went to Harvard because it was one of the few universities about which she knew anything. That she spent 10 years researching policy on subjects such as domestic violence and child abuse, which drove her to run for election so she could affect change. That for many years her mother was a Democrat and, although her father never told her as much, she thinks he was a Democrat, too.

To better know our new president, we talked with Healey. Here we share some of her stories.

Q: You grew up in Daytona Beach, Fla., but were born in Nebraska. Do you have any memories of it?

A: I actually have no memory of that. My parents were both native Floridians. My father was a real estate developer, and his work occasionally involved travel to develop subdivisions in other places around the country. One of those was in Omaha, Neb., so I was literally born while my parents were living in the model home of a subdivision. And my mother could not stand the snow. It was way too cold for her. So she implored my father to move back after two years, and we were back in Florida before I could even remember any bit of being in Omaha.

Q: Looking forward to what was sort of your first foray into public service, you were class president in high school.

A: [Laughing,] I was president of student council my senior year, and I was class president every year before that.

Q: Why did you want to be part of student government?

A: I think I’ve always been interested in having an impact on my environment and being part of a community. I’m an only child, so maybe I was looking for a way to gather people together around me. I had a wonderful, loving home, but both my mother and father were only children as well. So my family was a very nuclear three. Perhaps I have always valued my friends and my community highly because I view them as an extension of my family.

Q: What would you say impacted you most during your school years?

A: I would say a couple of things were formative for me, first of all, my mother being an elementary public school teacher. She taught at the school I attended, so I was always “mean Mrs. Murphy’s daughter.” She was an excellent teacher and still has students coming back to tell her 40 years later what a profound impact she had on their lives. At that time, the public schools that I attended were not very high quality, and they were really struggling. We had teacher strikes. We had racial disturbances during integration and busing, so this was not an atmosphere that was conducive to learning. My mother, who continuously valued education, was the most important intellectual influence on me.

The second big impactful experience was that my dad had a heart attack when I was 15. I was a sophomore, and he wasn’t able to work after that. We had never been wealthy, but then we were dependent upon my mother’s salary, which at that time was really almost shockingly low for a teacher with a master’s degree. I will always remember when I got my first tuition bill from Harvard, which included housing and food. It was around $15,000, and my mom was making $12,000 a year. So I was very grateful to her and to my father for the sacrifices they made so I could have my education. I received grants from Harvard, but I could’ve gone on a full scholarship to other colleges. They wanted me to go to the best college that I could. I think that connects strongly with my desire and my focus throughout my life on providing those kinds of educational opportunities for others. Education matters and is probably the most transformative force in the world.

Kerry Healey developed her sense of community service by watching her parents. Emulating their actions, she has followed through not only in politics but also in philanthropic endeavors. Several of Healey’s recent projects focus on enabling social change.

Q: What is the Public-Private Partnership for Justice Reform in Afghanistan (PPP), and how were you involved?

A: It’s a committee that explored ways in which American lawyers, judges, law firms, and law schools could begin to interact with and support the nascent legal community in Afghanistan. It’s a creature of the State Department, and one of many public-private partnerships that the government was exploring. I founded Friends of the PPP, which is the nonprofit arm responsible for implementing the PPP’s programs. Over time Friends evolved into a scholarship program for promising young Afghan lawyers and judges who are looking to get their Master of Laws, their LLM degree. That degree was not available in Afghanistan. It still is not available in Afghanistan. Yet it is a requirement to have that degree in order to teach law in Afghanistan.

We bring the best and the brightest Afghan lawyers to the U.S., about a dozen of them a year. And we have them sign a contract that they will return to Afghanistan to occupy positions of power and influence within their government or their society. Many of our graduates actually teach at as many as three law schools because they’re in such demand. One of the program’s alums founded his own private law firm and is very successful internationally. He has taken the revolutionary step of hiring female associates because of the openness that he saw here in the U.S. He would like Afghan women lawyers to have those same opportunities. We have three of our female graduates from the program who already are diplomats and are in line to become ambassadors at some point in their careers. And, again, that’s something they couldn’t have done without a higher degree.

Q: How about your humanitarian work?

A: A friend of mine, Jarrett Barrios, is Cuban by background, and he wanted to reach out to schools for the disabled and libraries for children in Cuba. I have traveled to Cuba on several occasions with him, visiting schools for the blind or other physically disabled children. We also visited some very talented students who had special needs, musically talented students who didn’t have proper instruments and so forth. It was a moving experience for me to see all of the unmet needs in Cuba.

I had been to Cuba before with [the NGO] Caritas Cubana, assisting with some of the distribution of aid. A local Cuban leader, Consuelo Isaacson, is the founder of Friends of Caritas Cubana. She had invited me to become a part of that organization, and it has also been an extremely inspirational and educational process. One thing that group is currently interested in doing is working with the Cuban and U.S. governments to provide micro-financing to some of the people in Cuba who are now free to be self-employed, but who lack the resources and the skills to become entrepreneurs.

Q: Do you think the Cubans will be successful?

A: I think the challenges are even more daunting for entrepreneurs who have not only no capital but no access to basic commodities. When I was there I saw, for example, how right after the restrictions had been lifted on entrepreneurial activities, the citizens did things immediately. They took old beer bottles and made marinades and put corks in the top and were selling those concoctions on the street. They took their sugar rations, which is the one thing there is plenty of, and they baked little cakes. I remember seeing this card table out on the street in Havana with five beautiful little pink frosted cakes that were for sale. As soon as it was legal to begin being entrepreneurial, the Cuban people wanted to find ways to do it with just the materials and resources that they had. But they could do so much more with proper support and education. I hope maybe as the leader of this college that I’ll have the opportunity to engage in that project.

Q: And then there’s Political Parity.

A: This is really the brainchild of Ambassador Swanee Hunt [at Harvard and Hunt Alternatives Fund]. She and I have come together to promote a project that is nonpartisan and focused on advancing women’s participation in high-level electoral politics. We recognize that both sides of the aisle have a serious problem with underrepresentation, and both parties bear a burden in that regard.

We have tried to craft research projects or interventions that benefit all women by either informing them about what the obstacles are and how to overcome them, or by confronting social forces, like sexism in the media, which impact all women across all ideologies. One of the most interesting projects we’ve done is called Name It. Change It. It is a resource for women who are running for office and for political parties to report sexist coverage in the media of any female candidate or sexist tactics in a campaign so that the behavior can be shamed and brought out and highlighted. It’s been enormously successful.

Q: You took a job when your dad became sick.

A: I started working at minimum wage in 1975, which was around $2 an hour as I recall, at a local souvenir shop. I sold puka shell necklaces and printed T-shirts, and I cleaned. I did that illegally for a year. I wasn’t supposed to be working yet because I was 15. But it certainly taught me a lesson about what it means to work for minimum wage.

I was working there probably 30 or more hours a week, and I quickly thought that what I wanted was to get a job that was not minimum wage. I had been the school reporter for our local newspaper and had a job writing a column for it about my high school. That didn’t pay much, but it did introduce me to the editor of the newspaper. She and her husband owned the newspaper. They were very forward-thinking and wanted to be the first computerized typesetting operation in Florida, and they wanted me to assist in that.

Q: What did you know about computers?

A: Well, it was a very odd moment in time when the U.S. space program was winding down and a lot of the G.E. rocket scientists who had been working on the Apollo program were told to go back up north. Some of them broke off and decided to start a computer science department at the Daytona Beach Community College. Now imagine this: It was a typical community college, and these rocket scientists are teaching young kids BASIC and Fortran and COBOL and assembly language programming. At 16, I took my savings from working at the shell shop and went to the community college to study with rocket scientists. I learned enough programming so that I could then go back to the newspaper and work in research and development. We installed four minicomputers. They still ran on paper tape at that point, and I actually wrote all of their early word processing programs. That paid quite well. That was $4.50 an hour, and that taught me the important lesson that education also results in higher pay.

Q: After high school you went to Harvard. Why Harvard?

A: I came from an environment where no one knew anything about any of these institutions. I knew the name of Harvard. I had been reading a lot of Victorian novels, so I knew about Oxford and Cambridge as well. My father had briefly attended Duke before World War II, so I knew about Duke. But beyond that, I really knew nothing. When I said to my high school counselor, “I think I’d like to apply to Harvard,” she said, “I think it’s in Connecticut.” This was before the Internet, so I had to go to a library and look up the address to figure out where these places were. I really had no idea of what I was doing when I applied to Harvard. I just knew that it existed and that it had a good name.

Q: When you arrived in Cambridge to attend Harvard, how did it feel?

A: I was as naive as you could possibly be. It was a big culture shock for me coming to Massachusetts. I had never lived in a city. I had never seen homelessness. I had never encountered the diversity of political opinions that I was seeing there. And, of course, the intellectual environment was spectacular. I was entirely self-taught in terms of the arts and the humanities. I had been able to study computer science with very smart folks, but the rest of my education was completely self-taught. So I struggled. I had never been asked at school to write a term paper or read a whole book. I had read many books, but I had read them without any direction. So a lot of what I wanted to do once I got to Harvard was to restudy many of the things that I had read, but with professors who could tell me what the context was. I quickly found out that I mispronounced a slew of words because I had never spoken them. That was pretty humbling.

Q: At Harvard you joined the Republican Club. Why? What connected you with that party versus the Democrats?

A: I didn’t feel connected to the Republican Party at all. What I felt connected to was a set of values that I had seen demonstrated in my parents. My parents had never discussed politics. They abided by that old rule of not discussing sex, religion, or politics. So it was one of those things where I simply tried to deduce what my parents’ political views were from their values and their actions. I saw that they believed in public service strongly, my dad being in the military, my mom as an educator and a community volunteer. I saw that they were both deeply religious and committed to their different churches. My dad was Catholic, and my mother was an Episcopalian. And I saw that they were dedicated to family.

I heard a great deal about their experiences during the Great Depression and World War II, and in particular their economic conservatism really came out through those experiences. They felt strongly that they needed to be independent of the government, that you needed to work hard to support yourself and your family, that you needed to give back to your community, and that you needed to help those in need. So those were the values that I grew up with. In my mind, I made the leap to imagining that those were values associated with the Republican Party.

When I turned 18, I told my father that I had registered as a Republican. He had one of the few outbursts I ever heard him have—actually, probably the only—where he said, “That’s the stupidest thing you’ve ever done. Now you’ll never have anyone to vote for.” Because at the time, everything in Florida was Democratic. There were no Republican candidates whatsoever. So although we never had a discussion about his politics, and he died without me knowing it for sure, I suspect that he was a Democrat. And now I know that my mother was, in fact, a Democrat. She was an FDR Democrat. She confessed that to me when she came up here and I said, “I hope you’re going to be voting for me,” and she said, “Well, I’ll have to change my party.” [Healey’s mom has since changed parties.]

Q: You also went to Trinity in Ireland for a PhD. You met your husband there?

A: He and I were on Rotary International Ambassadorial Scholarships. After I had lived in Dublin for three years, my husband went back to the States to go to Harvard Law School, and I followed shortly thereafter. I spent a year as a visiting researcher at Harvard Law School.

Q: What next?

A: I started working at Abt Associates, [a research firm focused on health, social, and environmental policies and international development], in its law and public safety department to pay my husband’s tuition.

Q: You worked there for 10 years, and it seems as if the subjects you researched—child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, gang violence, witness intimidation, drug crimes—influenced much of what you’ve done in the rest of your life.

A: Yes. It was an interesting moment to be involved in criminal justice, because criminal justice per se wasn’t a topic that people studied. When I first started working in that area, Abt Associates had people who had doctorates in history and physics and sociology and political science. We were all coming at these issues from different silos of perspectives. Suddenly it occurred to people that, oh, we should be looking at this as a much more integrated sociological issue. We should be taking in pieces of health as well, and looking at some of these problems as addictions and disease that also need treatment. So suddenly it was as if something broke open and the perspective on criminal justice was much broader.

Q: In 1998, you decided to run for state representative. You lost, but what had spurred you to run for office?

R: I had been working on a number of exciting, important issues, including drugs and gangs and domestic violence, child abuse and neglect. And I thought that my colleagues and I had some answers that were important for people to know about, but it was clear to me that no one was listening. There was a disconnect between the academic community and the policymaking community, the people who had the power to actually implement policy. So the only way I could think of to span that gap was to become one of those people with the power to implement policies.

I literally went to the State House and to the State Bookstore. It’s on the bottom floor there, and I got a little booklet. I can still see it in my mind. It said this is what you do if you want to run for office. It had a checklist in the back, and I just went down the checklist, and that’s how I got into politics.

Q: Looking at your time as lieutenant governor, what are the top three things that stand out for you?

A: It’s funny, because some of the biggest things we accomplished, like health-care reform, probably aren’t going to be one of the top three. But one thing that really stands out for me is Melanie’s Law. That wasn’t something that I had intended to do, but when I got into office, I realized the scope of the damage that was being done by our very weak drunk-driving laws, and how many people were being killed by drunk drivers each year. Beyond that, all the people who were being injured and maimed, and all the families being impacted by the deaths and the disabilities. It was a vast problem. It was unconscionable because the reason why the laws were so weak was because a third of our legislature were personal injury lawyers. They just didn’t want change in the system. You would find people who had been arrested for drunk driving at a serious level of intoxication, maybe 10 or more times, and they would still be on the roads because these lawyers knew how to advise people to get off. It was a big battle, and I feel very good that we won and created legislation that was meaningful.

Q: What talent do you have that most people don’t know about?

A: I am a good cook, actually. When I was in Ireland, I took a course at the Cordon Bleu. I’m also pretty good at pastas of all varieties.

Q: What’s a guilty pleasure?

A: At the moment I’m sort of obsessed with Game of Thrones.

Q: A favorite family vacation?

A: I like going anywhere with my family. My son and daughter and I were reminiscing the other day about a particularly fun several weeks we spent in Sonoma while my son interned at a winery. He was too young to drive, so I had to drive him to the winery every day. My daughter and I took cooking lessons while he was working.

Q: Do you have a favorite sport?

A: I’m not athletic in any capacity. Please protect me from myself.

Q: A favorite movie?

A: I like anything with Daniel Day-Lewis and Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête.

Q: Do you have a favorite band?

A: I like indie music mostly. I like The Lumineers, Metric, The xx.

Q: Have you gone to any concerts recently?

A: I went to Muse and the Silversun Pickups. I was definitely too old to be at Muse. That was embarrassing.

Q: What’s your dog’s name?

A: We have a boxer. When we got him, my daughter was watching Spartacus. So his name is Crixus. I’m looking forward to bringing him to Babson.

Q: What next?

A: I worked with then-senator Steven Tolman to establish three recovery high schools. There were a number of young people who were recovering drug addicts. They’d gone through treatment and were clean and were interested in attending school, but they couldn’t go back because there really aren’t any drug-free high schools in the entire commonwealth. So they would have to go back and see their old friends with whom they used to do drugs. They would go back and see their old drug dealer. Kids were having to choose between sobriety and their education, and that seemed wrong to us. Senator Tolman and I were able to work across the aisle to do something that in retrospect was almost impossible to imagine. We established three schools in a year and gave seed money to get them going. Now there are waiting lists for these schools. They are true, drug-free environments, where therapy and support is built into the curriculum. And those kids are going to college. It’s so exciting when I go to a graduation. You hate to think that anyone’s life could be ruined at 18 by drug addiction.

Q: And your third?

A: I was at a press conference announcing this new technology that we were going to be using with Level 3 sex offenders. We had totally revamped all of the sex offender registry, and one of the technologies that came out was this GPS tracking bracelet that you could use for monitoring. But it had something new beyond just the basic tracking. You could draw safety zones around certain points on the map. So, for example, in the case of sex offenders, you could draw zones around elementary schools or playgrounds. If that person walked into those areas, then the police or their probation officer would be called automatically, saying that the offender had violated the safety zone.

So I’m listening to this and I’m thinking, oh, my gosh, this is the technology that could right a fundamental injustice of our criminal justice system, which is that women or anyone who has obtained a civil restraining order against someone who is harassing or attacking them can’t do anything to enforce it. The restraining orders are just fundamentally unenforceable, because there aren’t enough police.

Let me take that a bit further. What’s the consequence of that? Women, victims of domestic violence in particular, would know that they were in great danger and realize that no one could actually protect them. So they would become homeless. They would take their children out of school. They would leave their jobs because they wouldn’t be safe in their employment. Suddenly, you go from being a victim to being a homeless, destitute victim with children who are disoriented and unhappy and who are going to suffer as a result of having to leave their school and friends and so forth. That’s not fair. Why should you as a victim be the one to pay the terrible cost of trying to protect yourself?

So when I was looking at this technology being rolled out for sex offenders, it suddenly occurred to me that you could use these exclusion zones to place protection areas around a woman’s home, around her place of work, around her children’s schools, and that you could turn that paradigm on its head so that the person who was the victimizer would be the person paying the price for that conduct, not the victim. I was enormously excited about this and went to Diane Rosenfeld at Harvard Law School, who was a member of our Governor’s Commission on Sexual and Domestic Violence, and asked her to help me draft a law that would make the violation of a civil restraining order a criminal act punishable by the imposition of this sort of GPS tracking.

You can’t protect someone the first time an order is violated. We could never figure out how to do that. But the first time the restraining order was ineffective, that became a criminal act. I was able to work with Jarrett Barrios, who was a senator at that time from Cambridge. He and I worked across the aisle to get that passed, and it was signed the last day before I left office. Diane has taken the legislation around the country, and I believe that it is now law in 20-plus other states.

Q: Now that you’re out of politics, what do you think you’ll miss the most?

A: I think probably some of the camaraderie and the great friends that I made. When you work together for any purpose, you bond closely with others.

Q: What will you miss the least?

A: That sort of tense feeling in your stomach before you pick up and read the papers every day. I can do without that.

Q: Why did you want to become president of Babson? How did you even know the job was open?

A: Well, that was easy. I got the proverbial call from the headhunters.

Q: I wouldn’t have thought, “Hey, there’s an opening for president at Babson, let’s call Kerry Healey.” You know?

A: Exactly. No, you’re exactly right, and I was joking with the search committee that the day before I received a call asking me to come in and speak with them, my mother-in-law had said, “I know what you should do. You should be the president of a college.” And I had replied, “You know, you have to be asked.”

Q: So when you were asked, what went through your head?

A: That my mother-in-law was right again, and that’s a lesson that we should all learn. I had a little knowledge about Babson, not a lot. But the more I learned, the more excited I got, the more it seemed that all the things I had done throughout my life fit within the Babson vision. While I had never imagined myself as having any sort of unifying principle to my activities, once I learned about Babson’s commitment to Entrepreneurship of All Kinds, and Babson being a driving force for change in the world, I realized that this philosophy had been driving my choices of career and avocation throughout my life.

Q: How do you define entrepreneurship?

A: I like the notion of Entrepreneurship of All Kinds. I would put the emphasis on “of all kinds.” I expect us to continue to emphasize private sector entrepreneurship, but I would love this school to equally embrace social entrepreneurship and innovation within the public sphere. I believe that I was an entrepreneurial leader in government, and I would hope that there are more out there. We should encourage people who choose any profession to try to improve that area through creative and entrepreneurial thinking. I don’t think we should view Babson as a school that has any limitations or a school that would only be of interest to one type of student. I believe all spheres of society will be improved by applying Entrepreneurial Thought and Action.

]]>

Babson Landmarks

I remember an explanation that the bird structure [by Park Manor South] is actually a hand facing up. Notice that each of the fingers and thumb is the proper relative dimensions.—Jeff Mulligan ’82, MBA’85

Your article brought to mind another forgotten marker. In 1974, I was a senior contemplating life after Babson. I had taken a career aptitude test that indicated I was suited for a job as a Navy chaplain. My lifelong fascination with things nautical and my evangelical Christian persuasion had doubtlessly influenced the test results. Although I had been involved in the Babson Christian Fellowship, I had not the slightest interest in going into full-time ministry. I needed a proverbial “sign from heaven.”

One day I came across a plaque in an obscure corner of the old Newton Library [now Tomasso Hall]. The plaque commemorated that Babson had been the site of the U.S. Navy Supply Corps School during World War II. I had never heard of the Navy Supply Corps before, but I learned that Supply Corps officers were the Navy’s professional business managers. I was intrigued by the prospect of combining my Babson education with my childhood dream of serving in the Navy. After talking with a recruiter, I applied and was accepted into the Naval Officer Candidate School and Navy Supply Corps programs. A week after graduating, I began an exciting and satisfying career.—Matthew Bank ’75

]]>But then as you watch them, their bodies full of grace and strength, you start to marvel at what they can do. They amaze you. They make you rethink the limits of what is possible. As they strain to do the improbable, you admire their guts and their willingness to ignore society’s conventions, even if you never quite stop wondering about their sanity.

Margaret Schlachter ’05 of Salt Lake City is one of these crazy, boundary-pushing, take-no-quarter alumni. For her, marathons aren’t tough enough. Later this year, she’s running in 50-kilometer and 100-kilometer ultramarathons. In June, she ran 60 miles, the equivalent of back-to-back marathons and then some, before foot issues forced her to drop out of the Peak 100, a 100-mile race.

Schlachter also competes in obstacle course racing, these muddy, adrenaline-fueled events that seem like something out of basic training, or some sort of masochistic workout, with runners scaling walls, climbing ropes, crawling under barbed wire, throwing spears, and jumping over fire. Some courses confront runners with a field of dangling electric wires, which can carry up to 10,000 volts. “It’s a big pop and a really intense shock,” Schlachter says. “The best thing to do is run fast through the wires and get in and out as quickly as possible.”

The most grueling obstacle races last for hours, even days, and resemble forced marches. Last year, Schlachter ran in the Spartan Death Race and lasted for 25 hours before dropping out. That’s 25 hours of physical tests, such as lugging a kayak and a 40-pound pack for miles, while willing herself to put one foot in front of the other. The year before, she lasted 21 hours and made it through some 150 obstacles in the World’s Toughest Mudder. Hypothermia and hallucinations ultimately forced her to stop. “I was upset, getting so close and not making it to the finish,” she says. “But I am going back to the World’s Toughest Mudder this year to slay that dragon.”

PEACE ON THE TRAIL

When thinking of Schlachter’s athletic feats, that question creeps up again: Why? Why couldn’t she just do an easy-going three-mile jog? Why feel the need to run for dozens upon dozens of miles and be shocked by electric wires? As intense as her races and training can be, Schlachter says she finds peace in all the miles. Depending on what races are coming up, she may run anywhere from 30 to 70 miles in a week, which includes a long outing every Sunday in the hills and mountains around Salt Lake that can last six hours or more. On top of that, there are many trips to the gym for strength training, but Schlachter finds it all therapeutic. “On long runs, you and you alone are on that trail,” she says. “It’s time to be by yourself, away from your phone. It’s you and your thoughts.”

Photo: Tobias MacPhee

To train for her long and intense races, Margaret Schlachter ’05 not only runs for miles upon miles around Salt Lake City, but she also regularly hits the gym for strength training.

Schlachter hasn’t always been such an uncompromising athlete. She may have played two sports at Babson, but she was goalie on the lacrosse team so she wouldn’t have to run around the field. After college, fitness wasn’t a priority. She coached high school lacrosse and alpine skiing, but she didn’t go to the gym and enjoyed wings night at the pub a bit too much.

Everything changed in 2010 when Schlachter entered her first obstacle course race. It inspired her. This was raw, messy time spent in nature away from life’s digital clutter. “These races speak to this primal need,” she says. “It’s very real. You’re in the mud. You don’t get that playing a video game.” Just like that, fitness was no longer an afterthought. More races soon followed, and she began tackling longer and more severe competitions. In just a short time, she became a consistent top finisher. In 2012, the Spartan obstacle race series ranked her the No. 5 woman in the world.

As racing and training engrossed her life, Schlachter made what seemed at the time to be a small decision: She started a blog called Dirt in Your Skirt about her running adventures. “It started as a personal blog for me for accountability,” she says. “At first my mom was the only one who read it. Then it started to grow.” Its popularity opened up entrepreneurial possibilities. By 2012, it was receiving about 1,000 hits a day and was the centerpiece of a business enterprise Schlachter started that focused on obstacle and endurance running. She was selling merchandise such as T-shirts and patches, and she was picking up sponsors.

Photo: Tobias MacPhee

With her blog and business growing, Schlachter was still working her day job as head of admission at a private school. It was a good gig, but with Dirt in Your Skirt and her training taking up so much time, something had to give. In July 2012, she quit her job. This was untested territory. Schlachter was the first woman to devote herself full time to obstacle racing. The move stunned friends. “I still have friends who think I’m crazy,” she says. A year later that decision is working out as Schlachter continues to expand her business and her profile. She offers coaching, runs a summer training camp, writes columns for the online site FitnessRX for Women, and is a contributing editor for Mud & Obstacle Magazine, set to launch in the fall. She also has a book coming out in 2014.

Through it all, she keeps moving. There are always more miles to go. When her body aches, she’ll acknowledge the pain in her mind and push on. She’ll think, I can go a little farther, and then, a little farther after that. “Physically, our bodies can take a lot,” she says. “People say this, but it really is all mental. It is really amazing what the brain can do.”

She remembers trying to climb a rope in a race, her hands cramping after swimming through a chilly pond. “It was so cold. My body froze,” says Schlachter, who somehow compelled herself to keep climbing. “You just got to go do it. You got to dig a little deeper and find out what you can do.”

A BETTER SELF ON THE MAT

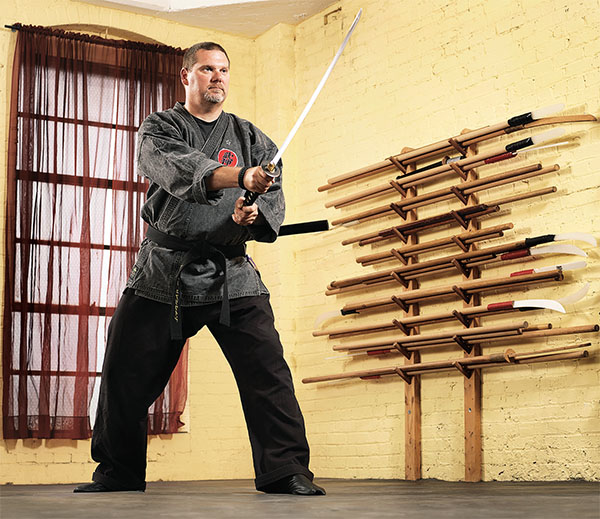

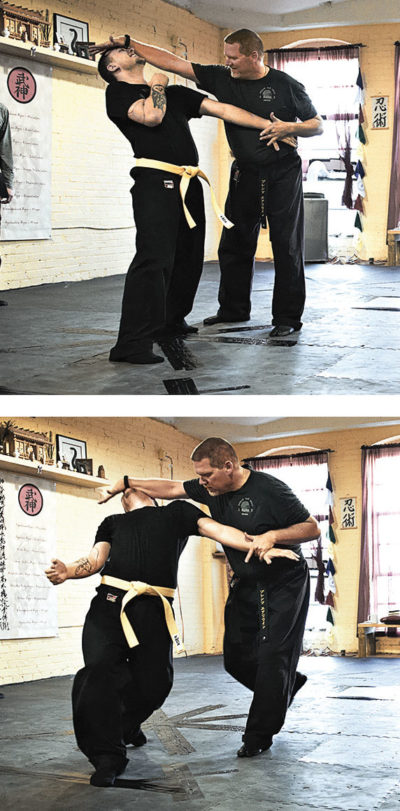

Brent Earlewine, MBA’10, can inflict a lot of pain. Not that he wants to. He’s a ninth-degree black belt in Budo Taijutsu, a martial art that traces its roots back some 2,500 years to samurai in Japan. Those who practice it are known as the Bujinkan, which translates loosely to “house of divine warrior.”

Photo: Mike Basher

Brent Earlewine, MBA’10, is a practitioner of a battlefield art that requires strength of body and mind.

Much like Schlachter’s running, Earlewine’s martial art requires strength of both body and mind. His training is cerebral. Ask him what he’s studying, and words seem inadequate. “I’ll give you an answer, but I’m not sure you’ll understand,” Earlewine says. Check out his Twitter page, and he sounds almost like a Zen master. “You have to learn the structure before you can throw away the structure,” reads one.

A 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike ride, and a 26.2-mile run. These daunting distances make up the Ironman triathlon, and they are the numbers that Nancy Gomes ’93 ponders in her mind. Could she do it, she wonders. Could she handle these distances?

The Franklin, Mass., resident already ran a half-Ironman last year on a tough 97-degree day, one in which she constantly doused her head with ice water. “It was hot. It was humid. It was gross,” she says. Despite the heat, the 70.3-mile race (half the full Ironman distance) was a great experience, save for the running. Pounding the pavement isn’t her thing. “I enjoyed the bike and swim,” she says. “I maybe enjoyed the first two miles of running. Your legs feel like bricks.”

To further test herself, she’s participating in two more half-Ironmans this summer. If those go well, she’ll sign up to do a full Ironman in 2014. From the relentless workouts to the loss of downtime to the potential to annoy even the most patient of spouses, Gomes understands the competition is a major commitment. It takes a solid year of training. “You have to go all in,” she says. “I think I know how much suffering is involved.”

Gomes played soccer in high school and at Babson, but she wasn’t always such a serious endurance athlete. About five or six years ago, a friend mentioned a sprint triathlon, a shorter race that serves as an introduction to triathlon competitions. She signed up for it, even though she had to learn how to swim, and soon was hooked. Longer races have ensued, and her training regimen has grown rigorous. In a typical week, she’ll work out 12 to 14 hours. That means training most days both before and after work, each session lasting one to two hours. Longer weekend workouts follow. “It makes you feel positive to push yourself,” she says. “I love the challenge. You could say it’s addictive.”

Triathlons also are a mental test. Before a competition, she thinks of what can go wrong—a leg cramp, a flat tire—and how she will handle it. As she races, she concentrates on keeping her pace steady and not going too fast. “You have to hold yourself back,” she says. “You have to stay in the moment. It’s a challenge to stay focused.” To keep going mile after mile, she thinks of Boston Children’s Hospital, the charity she runs for. She thinks of those who supported her. And she thinks of the finish line, which will be a welcome sight if she ultimately races in an Ironman. “People think we’re crazy, but that feeling of crossing the finish is very motivating,” she says. —JC

To illustrate the importance of mental vigor to Budo Taijutsu, the Pittsburgh resident talks of the astonishing sakki test, a requirement for all the art’s practitioners hoping to earn their fifth-degree black belt. The test, which is administered only in Japan, consists of one challenge. The test takers kneel on the floor with their eyes closed, and behind them stands the soke, or grandmaster. He holds a solid wooden sword above their heads. “It’s a pretty version of a baseball bat,” Earlewine says. Without warning, the soke brings the sword down, and the test taker must sense it coming and duck out of the way. “Trust me, you can’t hear it,” Earlewine says. “You have to be in the moment.” Earlewine recalls kneeling, concentrating, waiting for the soke to act. Then came an otherworldly signal. “I heard him in my head, ‘I’m about to cut. You need to get out of the way,’” says Earlewine, who did just that and earned his belt.

That’s a jaw-dropping feat, one that’s hard to believe, but Budo Taijutsu isn’t simply about mental acrobatics. It’s also about brute force. Unlike other martial arts that emphasize sport and exercise, it’s designed for one main purpose: to hurt people. Budo Taijutsu utilizes throws, hits, takedowns, and joint locks, which painfully bend the body in a way it’s not supposed to go. Swords, spears, and staffs also are used. “It’s a battlefield art,” says Earlewine. “It’s a zero-sum game.”

Earlewine began studying martial arts when he was 17. He’s now 44. “I couldn’t imagine not doing it,” he says. “It’s not a hobby. It’s become a part of who I am.” As a teenager, he wanted to be a “badass,” and the exotic nature of martial arts intrigued him. In time, though, those allures faded. He first studied Tang Soo Do, a Korean martial art, but he grew disillusioned that it was superficial, that it didn’t offer anything deeper than sweating on a mat.

Photos: Mike Basher

He took up Budo Taijutsu in 1996 and has been at it ever since. Such longevity is unusual. Earlewine estimates that out of every 100 people who start martial arts training, only two or three will earn a first-degree black belt. Of those, only one in 10 will make it to second degree. Around the world, fewer than 200 people are rated as highly in Budo Taijutsu as Earlewine, who is only one belt away from reaching 10th degree, the highest level. He’s so highly rated that to train, he travels every four to six weeks to where the most senior instructors live. He goes all over the country, and he also has taken three trips to Japan to study with the soke.

Hearing about Earlewine’s commitment, the same question pops up: Why? Why is he still at it? Doesn’t he already know enough to defend himself? “I’ve known how to physically handle myself for a long time,” Earlewine says. “It’s no longer the main reason I do this. When you know you can truly hurt someone, you wonder, is it worth it?” As part of his training, he has learned how to project his inner strength and confidence. “You gain a sense of presence,” he says. “People realize they shouldn’t mess with you.”

For Earlewine, studying martial arts has been transformative. Similar to how Schlachter finds fulfillment on the trails and in the gym, he finds it on the mat, in the flow and grace of his actions. “There’s peace in the movement,” he says. “It changes you and how you think.” As he has earned higher and higher belts, Earlewine has become someone not afraid of challenges, someone who’s an example to others, a teacher. While he works as a manager at Avaya, a telecommunications company, he and his partner operate a dojo, or training facility, called Pittsburgh Bujinkan Taka Seigi Dojo. The pair originally had started a website to document their training, but the site found an audience of people looking for instruction. The two had never planned on running a dojo, but after first offering a popular class at a local community center, they opened their facility in 2003.

At the dojo, Earlewine watches the new students who come in with the chip on their shoulders, the ones who want to be tough, as he did when he started. Slowly, they mellow. That chip disappears. “It’s not about beating someone up,” Earlewine says. “It’s about being the best version of yourself.”

CHALLENGES IN A KAYAK

Dave Lamoureux ’89 is a fisherman, of a sort. He has his unique way of fishing for bluefin tuna. It’s a bit, well, different. Waking up at 3 or 4 a.m., he drives to Provincetown, Mass., on the tip of Cape Cod. There he puts his kayak, named Fortitude, in the water and proceeds to paddle out into the open ocean. After about 90 minutes, he reaches his fishing spot, which is two miles or so offshore. With his line in the water, he waits for a bite from the big fish. It can’t be missed. “It stops the kayak dead,” he says. “Your body snaps. It’s like being in a car and slamming on the brakes.”

Photo: Tom Kates

Dave Lamoureux ’89 says tuna is the toughest, most powerful game fish.

Then comes what Lamoureux calls a “Nantucket sleigh ride,” as the fish pulls his kayak along at speeds of up to 20 mph. Reining the fish in can take as long as four hours. “You have to tire the fish out before he tires you out,” Lamoureux says. If he keeps the fish he catches, he then has to tow it back to shore, a hard and slow process. Add it all up, and he paddles 15 to 20 miles in a typical outing. While on the water, Lamoureux survives on 5-Hour Energy drinks.

Lamoureux’s unconventional fishing technique may be exhausting, but it’s also effective. He holds the record for the biggest bluefin tuna, 157 pounds, caught unassisted from a kayak, and his antics have been featured in The New York Times and on Animal Planet’s Off the Hook: Extreme Catches TV show. “I am the only person in the world who fishes like this for bluefin tuna,” Lamoureux says. “It’s dangerous. That’s why I’m the only guy in the world who does it.”

One thing making it dangerous is the fish he’s chasing. “Tuna is the toughest game fish,” says the Cambridge and Yarmouth resident. “A tuna is like hooking on a freight train. It’s a bull. It’s powerful enough to drag me and the kayak to the bottom.” Then there’s the matter of great white sharks. The water is full of them, and he has had several scary encounters. Once a great white zigzagged through the water trailing Lamoureux, who was dragging an 80-pound tuna catch back to shore. He actually had no idea the shark was there, and only found out later from a park ranger who was watching him through binoculars.

Photo: Tom Kates

Dave Lamoureux ’89

Another time, he paddled out early in the a.m., the morning’s calm broken when a great white attacked a seal pup about 30 yards away, the shark’s jaws clamping down with “awe-inspiring power.” At first, only the great white’s mouth was visible, but then the rest of its body rose to the surface. Lamoureux estimated it was 14 feet long. “I wasn’t putting a tape measure up to him,” he says. “It was bigger than my 12-foot kayak.”

At this point, that familiar question is begging to be asked: Why? Why paddle out into the vast ocean and worry about sharks? Why doesn’t he fish off a bridge, beach, or boat like everyone else? “I would fish off a bridge, but I would be bored,” Lamoureux says. “I get bored with things that are easy.” A lifelong fisherman, he took up kayak fishing in 2009, just one in a long line of extreme sports that Lamoureux has tried. “I was a rock climber till I got too heavy,” he says. “I was an extreme skier until my knees went.”

Lamoureux insists he’s not an adrenaline junkie. “I’m a challenge junkie,” he says. “I take on the challenge and mitigate the risk. It’s about risk management.” To manage the considerable risks, Lamoureux goes to great lengths. He has become an expert on the weather, so much so that commercial fishermen, many of whom were skeptical when he started kayak fishing, will ask him about forecasts. Being stuck in a kayak during an ocean storm would not be fun.

Photo: Tom Kates

Dave Lamoureux ’89