In Africa in the early mornings, so the story goes, the gazelle wakes up knowing one blunt truth: To survive, it must run faster than the lion. At the same time, the lion wakes up knowing an equally hard truth, that if it doesn’t run faster than the gazelle, it will have nothing to eat.

“Whether you’re a lion or a gazelle, you’ve got to get up and move in the morning,” Blank says, “so I’ve got to get up and move.” Blank is, indeed, a man in motion. Sixteen years have passed since he stepped away from Home Depot, the retail giant he co-founded, but the 75-year-old is far from retired.

Most visibly, he is the owner of the Atlanta Falcons football team. On any given Sunday, he can be seen sporting a touch of Falcons red and cheering on the players, even dancing with joy after a big win. Being an NFL owner has brought him both epic highs and lows. Last February, as millions watched on TV, the team lost a big lead and let a Super Bowl victory slip away. But this season has brought the opening of a dramatic new home for the Falcons, the $1.6 billion Mercedes-Benz Stadium, an immense and impressive structure that Blank calls “a dream come true.”

Blank has plenty to keep him busy outside of football as well. He’s the owner of the Atlanta United soccer team, two Montana ranches, and the PGA Tour Superstore, which has locations across the country. He also is dedicated to philanthropy, following the lead of Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates by signing the Giving Pledge, a commitment by billionaires to donate at least half of their wealth to charity. Blank has promised to give 95 percent of his estate to his family foundation.

“I have all the things I need and want and could use, so it’s an opportunity to make a difference,” he says. “You want to have meaning in your life in some form or fashion, and meaning for me comes from making a difference in others’ lives.”

Blank recently sat down with Babson Magazine to talk about his filled-to-the-brim life, about his experiences with the Falcons and what he hopes to accomplish through philanthropy, and about how family and a desire to serve others rejuvenate him and keep him moving, just like that lion and gazelle on the plains of Africa. “I am busy,” he says, “but it’s all good stuff.”

Always Pushing

The home base for Blank’s businesses and foundation is the Arthur M. Blank Family Office, located in Atlanta’s Buckhead neighborhood. With artwork and Falcons memorabilia lining its halls, the stately and expansive building houses a ballroom, a library stocked with books on leadership and philanthropy, and meeting rooms named for Anne Frank and Silent Spring author Rachel Carson. In the waiting area, visitors can view Home Depot mementos, including the company’s original business plan.

One striking aspect of the office is its sculptures honoring Native Americans. At the foot of the main staircase, for instance, stands a life-sized sculpture of a Teton Sioux warrior. Having spent much time out West on his ranches, Blank is inspired by the history and culture of Native Americans, of how they cherish family and respect nature. He also has come to admire the values of the Western ranchers and farmers he has met. “They have a much more simple view of life,” he says. “A handshake means everything. A promise means everything.”

Blank sits for an interview in a conference room off his private office. On the walls hang his honorary degree from Babson and a certificate marking his 1995 induction into the College’s Academy of Distinguished Entrepreneurs. A glass of Diet Coke by his side, Blank wears a blue sport coat and looks relaxed. “Anything you want to talk about is fine,” he says.

For Blank, the year started with the thrill of the Falcons going to the Super Bowl, their first trip to the championship game under his ownership, and then the agony of seeing the team blow a 28-3 lead. “We never should have lost the game,” Blank says. “There’s no question about that.” He doesn’t dwell on it. The team is still full of talent, and so he looks to the future and keeps the loss in perspective. “Things happen and you learn from them and you move on. I’m not going to let it become a weight around my neck for the rest of my life, that’s for sure,” he says. “I’ve achieved what I’ve wanted to achieve, which was to create a competitive, winning organization that’s going to be sustainable over time.”

The stately and expansive Arthur M. Blank Family Office is filled with Atlanta Falcons mementos and art honoring Native Americans. The office’s library is stocked with books on philanthropy and leadership.

The stately and expansive Arthur M. Blank Family Office is filled with Atlanta Falcons mementos and art honoring Native Americans. The office’s library is stocked with books on philanthropy and leadership.

Lisa Chang, the senior vice president and chief human resources officer for Blank’s businesses, known collectively as the AMB Group, saw firsthand Blank’s attitude after the loss. “The day after the Super Bowl, we were on to the next thing,” she says. That didn’t surprise her. Blank is always encouraging his employees to keep trying, to keep moving. “There is no finish line” is one of his mantras. “Just when we think we got the cherry on top, he pushes us further,” Chang says.

Blank and the Falcons moved on in a big way from the Super Bowl with the opening of the 2-million-square-foot Mercedes-Benz Stadium, which also is home to the Atlanta United soccer team. “This is a very iconic and unique stadium,” says Blank, “probably the finest sports entertainment complex in the country today.” That may not be an exaggeration. When Blank and his team began the initial planning of the stadium about 10 years ago, the vision was to create something bold. Seating 71,000 fans for football games, it features a 58-foot-tall, 360-degree video board and a retractable roof with eight massive interlocking panels. For those feeling thirsty, the stadium has 1,200 beer taps.

In the weeks before the stadium opened, Blank focused on making sure it had a welcoming atmosphere for fans. The stadium employs a staff of 4,000, and Blank surprised newly hired ushers and concessionaires by showing up for their training sessions. “The grandeur of the building needs to be matched by the grandeur of our associate services,” Blank says. “We want our guests to feel like this is their home.”

A History of Building

Blank may have just built a stadium, but the first act of his career was spent building Home Depot, which he co-founded in 1978. When he stepped down from the ubiquitous home-improvement store in 2001, the company was the second largest retailer in the world after Walmart. “I had a wonderful 23 years,” Blank says, “and I was ready to do some other things.”

David Homrich, who has known Blank for 28 years, remembers the entrepreneur’s mindset as he left the company, with the possibility of new opportunities stretched before him. “In some respects, he was like a caged tiger,” Homrich says. “He wanted to run.” Homrich had served as Blank’s financial planner for 12 years before coming to work for him full time, and today he is the executive vice president, chief financial and investment officer of the AMB Group. The pair were having dinner together when Blank shared the news that he was leaving Home Depot. Homrich asked what the entrepreneur planned to do next. “I don’t know,” Blank replied, “but I know I’ll be active.”

A year later, Blank bought the Falcons, and since then he has found himself in the middle of the biggest spectacle in America: NFL football. Game days are filled with noise, cameras, and crowds, but Blank tries not to bother with all the pageantry. As an owner, he’ll socialize with sponsors, supporters, and officials at halftime and before the game, but during the game, he holes up with team executives and focuses on the field. He wants no distractions. “I’m an intense fan,” he says.

Before games, Blank also likes to visit with players on the field and in the locker room. “I try to spend a lot of time with our players, getting to know them, their families, their passions in life,” he says. When he chats with players, Blank aims to stay away from football talk. Because the average NFL career is only three years, he is concerned about their future plans. “They’re trying to figure out, ‘What do I do with the rest of my life?’” Blank says. “It’s hard.”

As the owner of a professional football team and soccer team, Arthur Blank believes in the power of sports to bring people together. “It’s a great venue for that,” he says. “You act as a catalyst for building community.”

While the Falcons’ head coach and general manager keep him informed about their strategies for the team, Blank gives them a wide berth. “I want to stay out of their way,” he says. “I don’t give any direction to any of our football staff on the draft, free agency, games, etc.” After games, he’ll meet with the coach for a debriefing, but not until the next day. “I don’t meet with him the day of the game, because it’s just too emotional, win or lose,” Blank says.

Beyond what happens on the field, Blank also focuses on the role that the Falcons play in the community. “It’s important for the team to give back, to win on the field and win off the field,” Blank says. “The expression we’ve always used is that there are two Super Bowls every year. The first is the one that you traditionally play on the field. The other is the Super Bowl of life. We want to win that one every year.”

The Art of Philanthropy

This drive to give back can be seen in Blank’s commitment to Atlanta’s Westside. An area plagued by poverty and high unemployment that lies next to the new stadium, the Westside once was home to civil rights leaders Julian Bond and Martin Luther King Jr. “Arthur said from the beginning that we could not have this iconic stadium on one side of Northside Drive and have these depressed neighborhoods on the other side,” says Penelope McPhee, president and director of the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation. “We had to make a difference to the whole community.”

Photos Courtesy of the AMB Group

Photos Courtesy of the AMB Group

Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the new home of the Atlanta Falcons, opened this football season. Costing $1.6 billion, the stadium features a uniquely designed retractable roof that employs eight massive interlocking panels.

To do that, Blank has invested millions in helping the Westside. As a deal to build the new stadium was finalized in 2013, the Blank Family Foundation pledged $15 million to the Westside Neighborhood Prosperity Fund, which invests in workforce development, education, housing, and other areas. This September, the foundation added another $15 million. The new stadium includes a 1.2-million-gallon underground vault to collect rain water, which helps alleviate flooding problems in the Westside. Other foundation initiatives, such as the Inspiring Spaces program that focuses on preserving and enhancing green spaces, have spent an additional $7 million on Westside activities. Plans in the near future include the creation of a neighborhood park on the site of the soon-to-be-demolished Georgia Dome.

All this investment has sparked corporations and other foundations to make their own donations to the Westside. “The vision has always been that we would be a catalyst, and others would invest with us,” McPhee says. The help is needed. Transforming neighborhoods and lifting people out of poverty isn’t easy. “It’s easier to build a stadium,” Blank says. “Changing people’s lives is a tougher row to hoe, but we’re working on it.”

Blank’s efforts in the Westside are just one part of his philanthropic aspirations. Since its founding in 1995, the Blank Family Foundation has contributed more than $300 million to organizations working in education, early childhood development, the environment, and the arts. That commitment will only grow with Blank’s signing of the Giving Pledge and his promise to donate the bulk of his money to the foundation. Contending that the “art of philanthropy, in many ways, is more difficult than the art of making money,” Blank spends considerable time evaluating nonprofits and figuring out the most effective programs to support.

Blank’s generosity extends to his alma mater as well. Through the years, he has sponsored scholarships, established an endowment to support the College’s entrepreneurship program, and funded Social Innovation Inventureships, which allow Babson students to tackle projects that make a social impact. The College left its mark on Blank, too. He remembers fondly his old professors, and he credits the campus offices he held for helping him grow as a leader. “Clearly, the education he received at Babson is in his DNA,” McPhee says. “He truly is, in the business area and in the philanthropic area, a serial entrepreneur. His vision is limitless. That reflects on the values of Arthur, but that also reflects on the values of Babson, too.”

Arthur Blank continues to find inspiration in his work and philanthropy. “Making a difference in the people we serve,” he says, “that’s what gives me the energy to do what I’m doing.”

All six of Blank’s children, including his youngest, twins who are 16, are involved in the family foundation to some degree. Spending as much time as he can with his family, which includes six grandchildren, is important to him. His wife, Angela, also has three children. In his conference room, a collage of family pictures fills the wall behind him. “I’ve got a lot of people to keep track of,” he says.

As busy as he is, Blank has taken some steps back from the day-to-day operations of his for-profit businesses, hiring a CEO in late 2015 for the AMB Group, though Blank continues as chairman and remains heavily involved in strategy. When asked if he has any plans to step aside fully, he states simply, “No.” He still has the drive to move, to plan, to act. “I probably always will,” he says.

]]>Queitsch knows that his business isn’t unique. “I’m not the first person to make a website with products online,” he says. Queitsch acknowledges that his products aren’t novel either. “Who you buy a pen from doesn’t matter for the customer,” he says. “It’s the same pen.”

For that reason, Queitsch thinks seriously about innovation. Looking to set the company apart, he constantly listens to the needs of his customers and suppliers and seeks inventive ways to refine the business, making improvements to its inventory management and the consumer experience of its website. The company may sell pens and paperclips, everyday items that can be found in a multitude of stores, but Queitsch wants shopping at OfficeRock.com to be easier and better than elsewhere. “Without innovation, we’re the same as everyone else,” Queitsch says.

But innovation doesn’t come easy. Smart business ideas, as Queitsch knows, don’t just happen. They take effort. To kindle creativity means bringing a thoughtful and deliberate approach to one’s work. “Innovation is a discipline,” says professor Jay Rao, who has worked at Babson for 22 years and teaches courses on innovation and strategy. “You can learn it, you can practice it, you can master it. It’s not magic. It’s not luck.”

FEEDING CREATIVITY

The need for innovation and creativity cuts across fields, whether you work at an architectural firm or an accounting firm, a tech giant or a tech startup, a vast corporation or a one-man shop. “Any business has to be creative to be relevant,” says Erica Zahka, MBA’16, founder and owner of Own The Boardroom. “It’s not only Apple.”

Based in Norwood, Massachusetts, Own The Boardroom serves as an on-demand professional closet, allowing customers to rent men’s and women’s attire for job interviews and business meetings. Zahka launched the venture late last year. She admits that the hectic life of a startup doesn’t always allow for the time or energy to come up with imaginative business strategies. If a problem arises, the best option is sometimes to “duct tape it” and move on. “Depending on the impact of the problem, ‘done’ is often better than ‘perfect’ in the startup world,” she says.

But one way Zahka finds inspiration is in the company of other entrepreneurs. She’s a recent participant in Babson’s Women Innovating Now Lab in Boston. In May, she won the lab’s Breakthrough Women’s Entrepreneurial Pitch Competition. “I am a huge advocate of WIN Lab,” Zahka says. “Being surrounded by people who are dedicated and passionate—it’s very energizing and motivating.”

Every Wednesday evening during the eight-month venture-accelerator program, she and her cohorts met to hear presentations and talk about their businesses. Problems were shared and suggestions were offered. Feedback flowed. “A lot of timesit was difficult to go to bed on Wednesday evenings,” Zahka says. “You had so much energy and so many ideas. You wanted to start working on something right then.” Her WIN Lab experience is now over, but Zahka still gathers with members of her cohort to chat about the highs and lows of their entrepreneurial journeys. “It’s always helpful,” she says.

Daniel Thomsen ’02 also relies on feedback from others. Thomsen is a TV writer, a career he decided to pursue after the collapse of the dot-com bubble forced him to reconsider his original plan, which was to join a tech startup after graduation. Driven by his passion for writing, he moved to Los Angeles and slowly but surely built a career. Through the years, he has written for a variety of TV shows, including Westworld, Once Upon a Time, Time After Time, Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles, and a Melrose Place remake.

When working on a script, Thomsen doesn’t have the luxury of waiting around for inspiration to strike. “You’re working in an environment with 150 to 200 people who are waiting for your script pages to appear before they can do their jobs,” says Thomsen. “As motivation goes, that’s fairly compelling.”

If Thomsen has script trouble, he turns to his fellow writers to help kick-start his creativity. “The most effective way to help a fellow writer is to listen,” he says. “Professional writers are very good at describing, sometimes in painful detail, the problems they’re having with a story.” Thomsen will sit down with the show’s other writers and hash out his script’s headaches. What’s missing? What’s getting in the way of a satisfying ending? Soon enough, people pitch solutions. Ideas fly, one on top of the other. “Just hearing another person’s spin on something, especially if they’re building on what you’re creating in a fresh or unexpected way, is inspiring,” he says.

Thomsen also absorbs insights and inklings from other sources—books, movies, the people he meets, the world around him. “If creativity is your output, you have to keep feeding your brain withnew and exciting input,” he says. “Then it’s up to you to take what you’re thinking about or feeling, and channel it into something useful.”

If he is really stuck, Thomsen changes his location. When the last script he wrote wasn’t clicking, Thomsen drove to Lake Arrowhead, a mountain town about two hours outside L.A. “Two nights in a completely different climate, around totally different people, and it jogged my brain to start thinking about my story problems from a new angle,” he says.

This strategy, of changing locales and getting away from routines and familiar surroundings, is an effective one, says professor Rao. Some companies try this tactic with their employees. One Southern California communications firm, for instance, gives its employees $1,500 every year to travel anywhere in the world and explore, says Rao. A Cleveland medical center, meanwhile, requires senior staff members to take time each year and observe operations in an industry unrelated to medicine. By experiencing something new, says Rao, employees are forced to look at the world differently. “The more they get out of their comfort zone, the more they observe and listen and question the status quo in their own businesses,” he says.

EMBRACING LIMITATIONS

When Ed Nilsson, MBA’97, needs to feel inspired, the architect doesn’t travel far. Founded in 1981, his firm, Nilsson + Siden Associates, works on renovations and new construction, designing such projects as office buildings, town halls, single-family residences, and medical offices.

While Nilsson says some architects return to Italy every year to recharge their imaginations, he simply strolls around town. He lives in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and his firm is located in nearby Salem. Walking around these two historic seaside towns, Nilsson seeks a fresh perspective, not by checking out contemporary architecture, but by looking to the past. Architects like him are perpetual students. “We’re always looking forward, but we also look backward,” Nilsson says. “Some people say it takes 50 years to learn this profession.” He finds that many modern buildings, designed with the aid of computer software, are too slick, too flawless. He likes the charm of the old buildings, how they’re a bit quirky and not always perfect. “The human touch is always evident,” he says.

When designing a project, Nilsson often faces constraints. Maybe the construction budget is small, or maybe he has to renovate a historic building and preserve as much of its character as possible. At this point, the key is not to fight the constraints, but to embrace them. Nilsson believes the process of working through limitations makes his designs stronger. “It makes you think sharper, clearer,” he says. “If you need something to make you think outside the box, constraints will do that.”

Years ago, he took on a project to convert a 19th-century machine shop at Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard into apartments. An earlier design by other architects proposed to fill the 500,000-square-foot building with spacious units, but when that proved too costly, Nilsson reconfigured the design. He scaled down the size of the apartments and preserved most of the open space in the center of the building as a landscaped atrium, taking advantage of the structure’s existing skylights. The end result met the budget and was a much more pleasing design, says Nilsson.

Similarly, TV writer Thomsen often finds his scripts must meet real-world parameters. “At the very beginning of the writing process in television, we call it the ‘blue sky’ phase, where there are fewer limits on what you can write,” he says. Then the budget arrives, and Thomsen becomes locked into certain locations or a particular number of cast members. He may later find out that an ambitious visual effect he wanted can’t be pulled off. “Suddenly your writing is being guided by dozens of factors,” he says. This requires a switch in mindset, as he becomes less like a writer with a story to tell and more like a problem solver with a puzzle to figure out.

For creators and doers in need of solutions and inspiration, professor Rao says they shouldn’t fret about taking someone else’s idea and adapting it for their own use. Don’t aim for 100 percent originality, he advises. “Real entrepreneurs don’t care for that. They don’t care for uniqueness. They look for an opportunity,” he says. “Shakespeare stole like crazy. Walt Disney borrowed ideas heavily and so did Steve Jobs.”

When she was putting together Own The Boardroom, Zahka looked closely at Rent the Runway, a service that allows customers to rent designer dresses. She put her own spin on the idea, but that business served as a model for what she wanted to do. “Whatever the situation is at hand, it’s always helpful to find an example where it appears to be working smoothly,” Zahka says. “Reinventing the wheel all the time is not efficient.”

One industry certainly not afraid to copy a good idea is TV. Reboots and remakes are plentiful. “It’s safer to produce entertainment that already has brand awareness built in,” Thomsen says. Original shows, even hits such as Breaking Bad and Mad Men, can take awhile to build a following. Make a well-known movie like Fargo into a TV show, on the other hand, and more people will check it out from day one. But Thomsen believes that even if writers are working within the confines of an old show or movie, they can still make fresh and innovative television. “I think there’s still plenty of originality to be mined,” he says.

Currently taking time to pursue his own projects, Thomsen has two ideas for shows in studio development, the first about people practicing witchcraft in Las Vegas, the other a castaway family drama, a kind of modern-day Swiss Family Robinson. He’s hoping to hear soon whether either will be greenlit for production, though one challenge with working in TV now is the glut of shows available for viewers. In the so-called era of Peak TV, a great show, no matter how compelling, can easily be overlooked. Thomsen avoids over-analyzing TV viewers. “You can get tied up in knots trying to chase audience expectations,” he says. “I still try to write from a simple place of, ‘What am I interested in watching?’”

CREATING CULTURE

Just like others, Toni Clayton-Hine ’93 is constantly seeking ways to feed her creativity. The senior vice president and chief marketing officer at Xerox, she looks at clever ads and innovative products, no matter the industry they come from, in a search for inspiration. Her mind is always working. “I have 100 ideas every day, and 98 percent of them are terrible,” says Clayton-Hine, who works out of the company’s home base in Norwalk, Connecticut. “It must be the way I’m wired.”

Clayton-Hine takes those ideas to her team and “walks the plank,” so to speak, encouraging staff to poke holes in them. By exposing her ideas to critiques, she is hoping to encourage other team members to bring their thoughts forward as well. “You want them to feel it’s a safe place to come up with ideas and discuss them,” she says. “They have to feel comfortable.” To further build a culture of openness and creativity, she takes care in hiring team members, networking to find the right job candidates. “I look for creative thinkers and creative problem solvers. Someone who looks at a problem as an opportunity,” she says. “I tend to hire for that profile. I don’t know if I can teach that.”

Although some well-known companies, such as Google and Southwest Airlines, focus on culture just as Clayton-Hine does, many organizations are not as deliberate, says professor Rao. “Usually, culture is left to the HR department,” he says. “Most executives don’t think that way. If you’re a Wall Street-focused, financially driven company, culture is not often on your radar. If you’re a startup venture, you’re thinking of survival, growth, and keeping your investors happy.” Other companies hire a bunch of smart people, give them amazing equipment, and then put them together to see what happens.

But if company leaders would realize they don’t have all the answers and welcome employee ideas, says Rao, they could create a fertile environment that is a powerful tool in fostering innovation. “We need to create this sandbox where people with diverse skills will question your thinking but not belittle it, learn from mistakes without fear of failure, and learn new things and then apply it back to the problems you’re working on,” he says.

In addition to culture, Queitsch of OfficeRock.com believes that frequent interactions with customers and suppliers can stimulate innovation. Once or twice a month he tags along with a company delivery driver on his route. Starting at 7 a.m. and not ending until all the deliveries are made, which could be around 6 p.m., the day is long, but Queitsch considers the time invaluable. Customers are glad to see him. “It’s always important to have your ears to the ground,” he says. “To create a good product, you want to listen to what your customers need.”

Nilsson, the architect, agrees. A big reason he pursued his Babson MBA was so he could better understand the economic demands and challenges of his clients. “You have to put yourself in their shoes,” he says. “Architects need empathy in order to best serve their clients.”

To address the needs of customers, Xerox tries to understand fully their work experience, says Clayton-Hine. The company doesn’t simply ask customers about the problems they are facing. Instead, Xerox takes a different tack, asking “How are you working?” and “How are you interacting?” By asking these types of questions, they are able to discover problems that customers might not have realized they had, says Clayton-Hine.

Such insight into customers is critical for innovation, says Rao. “I can’t expect you to wake up tomorrow and be creative,” he says. “You need to be knowledgeable about problems in the marketplace. What are customers’ pains?”

Feeling empathy. Building culture. Leaning on community. Adapting ideas. Overcoming limitations. Feeding creativity. Much goes into the quest for innovation. The work is hard, but the rewards are satisfying. Thomsen, the TV writer, admits feeling anxiety during the production of a show. “But when the work is over, and you’re screening an episode that came together better than you’d even imagined, it’s an irreplaceable feeling,” he says. “It never gets old.”

]]>After graduating from Babson, Heidinger headed to New York City to work for a small consulting and money-management firm that specialized in socially responsible investing. But she decided the fit wasn’t right, and within six months Heidinger accepted a position with FremantleMedia, a global television production company responsible for shows such as American Idol, The X Factor, and The Price Is Right. Her job involved supporting business that was generated by programs such as product placement. “The Coke cups on the desk that Simon Cowell and the other judges drank out of on American Idol? That was a deal that our team did,” Heidinger says.

She spent six years with the company, first in New York and then, looking for a warmer climate, in Santa Monica, California. Heidinger next took a special-events position with DreamWorks Animation, arranging movie premieres, global film launches, and company appearances at the Cannes Film Festival and trade shows. “It was an incredible company to work for, but I didn’t care much about the work I was doing,” she admits. “I was never star-struck. That made the 16-hour days really difficult.”

As her 30th birthday approached, Heidinger decided to fulfill a longtime dream by taking a three-week trip to Kenya. She went on safari and then spent a week in the slums of Nairobi, where she helped break ground for a women’s clinic and volunteered in an orphanage for children with addictions. The experience led her to question her career. “This world is so crazy. There are so many people in need, and here I was working in this posh job—but I was not helping anyone,” she recalls. “I was just making the wealthy wealthier and celebrating celebrities who already had everything they needed.”

At the end of her trip, she returned to California and resigned from her job. But perhaps even more surprisingly, she also realized that she wanted to break the pledge she had made as a teenager and head back to Buffalo. Her periodic trips home had intrigued her. She was discovering new restaurants and development in old neighborhoods, and Yahoo had opened a data center and customer-care facility. “More and more, you’d hear that some classmate from high school had moved back,” Heidinger says.

Around Labor Day in 2014, she packed her Mini Cooper and headed east, uneasy that she was moving back in with her parents and had no job or health insurance. But just a few months later in March, she was hired as director of special events and programming for 43North, a position that means serving as one of Buffalo’s chief cheerleaders.

In 2012, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo had unveiled the Buffalo Billion project to spur economic growth and job creation in the region. One of the initiatives included an annual $5 million business-plan competition that requires winning companies to move to Buffalo and stay for at least one calendar year. Heidinger’s employer, 43North, runs the competition, now in its fourth year. Each October, eight winners are selected and must establish operations in Buffalo by January 1. Heidinger helps employees of those companies settle into the Buffalo area and arranges entertainment itineraries that companies can use to impress important out-of-town visitors. “We recognize that if companies don’t love Buffalo, they’re probably not going to stay,” Heidinger says. “I do anything I can to open their eyes to what’s going on here and help them fall in love with Buffalo.”

Photo: Matt Wittmeyer

Colleen Heidinger plans to live on the second floor of the building she is renovating and open her own events business in commercial space on the ground floor.

Along the way, Heidinger appears to have fallen in love with her hometown as well. “The cost of living is unbelievable,” she says. “There’s no traffic. We have great dining. We have NFL and NHL teams, we attract all the shows and big bands, and after a night out you’re still able to get home in 12 minutes.”

She recently entered the Buffalo real estate market by purchasing a 1914 building in a revitalized area called Larkinville. She is rehabbing the building, planning to live on the second floor and open her own events business in a commercial space on the first floor. “I often tell kids that I mentor, ‘There’s no better place to fail,’” Heidinger says. “If this real estate project blows up, I didn’t use my whole savings account or sign my life away. If I did this in Greenwich Village, you can bet it would be all my money. If you have an idea you want to test out, or need to hire 20 people, Buffalo is a good place to do it.”

Still, coming home has had its challenges. Heidinger enjoys being part of a small, tight-knit community but notes that dating was tough at times. (She now is seeing “a very great guy.”) She also is grateful for Babson friends scattered around the country, including those in New York City and Boston who give her a regular place to land when she needs a big city fix. “I do need to get out of here sometimes,” she says. “But then I’m very happy to come back.”

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Dan Dalet ’03 co-founded SoloCoco in his homeland of the Dominican Republic to help the economy and provide employment for locals, many of whom are single moms.

Hope Through Work

Growing up in the Dominican Republic, Dan Dalet ’03 and his two brothers lived a comfortable life. They attended good schools, their father worked for a bank and later the auto company Fiat, and their mother was a portrait photographer. As a surfer, Dalet took full advantage of the white sand beaches and amazing weather.

But Dalet also knew the DR’s strong GDP and popular tourist resorts didn’t tell the whole story of his country. “If you drive 10 miles in the opposite direction of those beaches, you find yourself in poverty and underdevelopment,” he says. “As a youth, I always had the idea that someday I would come back to my country and add value.”

First, he traveled to Babson to earn his undergraduate degree. Intrigued by the world of finance, he worked for a private bank in Florida after finishing his studies, and then he helped establish a Boston-based hedge fund comprising entrepreneurial companies. But around the time of the economic collapse in 2008, Dalet began rethinking the long hours and stress of his job, and he couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that his work wasn’t making a lasting impact on the economy or people’s lives.

Dalet began to wonder if it was time to head home. He imagined doing his part for the local economy by launching a company, and he was casting around for ideas when a conversation with his parents grabbed his attention. They were talking about the health benefits of coconut oil. Initially, Dalet was skeptical, but then his uncle, a physician, chimed in, saying that he thought new research about coconut oil was compelling. It was the proverbial lightbulb moment. “I thought, we’re surrounded by coconuts here,” Dalet says. “Why aren’t we making very high-quality, organic coconut oil?”

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Photo: Roberto Muñoz

Dan Dalet (left) at SoloCoco

Historically, the Dominican Republic has harvested coconuts and exported them as produce or raw material. But Dalet imagined something new: processing the coconuts and turning them into high-quality products before export. So in 2011 he and his wife moved to the DR, and Dalet dove in, experimenting with the production process at a manufacturing facility he established in a rural area 3 1/2 hours from the capital. A year into the venture, however, Dalet hit a significant roadblock. When trying to recruit workers, he discovered that few were available, because most had left the rural area to find work in the city.

Undaunted, Dalet started over. This time he partnered with his cousin Abel Gonzalez, opening a new plant in San Pedro de Macoris, a city with a population of about 195,000 in the southeast region of the island. As they prepared once again to bring on staff, they advertised a willingness to hire applicants who lacked typical experience but demonstrated promise and a desire to work.

One morning in November 2014, they drove to their plant to interview potential employees. What they encountered stunned them. “There was a line of more than 250 women waiting outside,” Dalet remembers. Most were single mothers in their mid-20s, raising three to five children on their own. Many never had attended high school. One woman told Dalet that she was willing to do anything to feed her children, but no one would hire her.

“The sense of despair and hopelessness impacted us profoundly,” Dalet recalls. Although he always had been aware of income disparity in the DR, Dalet still was startled by the severity of the poverty and the lack of options for these women and their children. He and his cousin saw their upbringing and access to education with new eyes. “That day changed us as human beings,” he says, “and changed us as entrepreneurs.”

Running a successful company would no longer be enough. Dalet and Gonzalez made a strategic decision to launch as a socially conscious venture designed around the well-being of its workers. They called their company SoloCoco, which translates to “just coconut” in English. (“Just” is intended as a double-entendre, meaning both “simply” and “fair,” Dalet says.) They hired more women than they initially planned and created a flexible work schedule that would allow employees to work as little as one or two days a week.

Dalet has seen statistics suggesting that a high percentage of children in the Dominican Republic are born to single mothers. These children are more likely to experience poverty and drop out of school, he notes. Many don’t attend school because they lack basic resources, such as school supplies. Those who do attend often experience frequent illnesses and absences because of a lack of sanitation and basic health care. These factors put high school graduation out of reach for many children of single mothers, Dalet explains.

Faced with these daunting statistics, Dalet worked to earn certification by the Fair Trade Sustainability Alliance, a New York-based organization that oversees the well-being of a company’s workers. In addition to offering his workers health care, Dalet partnered with FairTSA to set up a co-pay fund to help with costs not covered by insurance and a fund to cover the cost of school supplies for employees’ children. Another initiative, driven by SoloCoco staff, focuses on employee housing and sanitation. Last summer, the company built its first concrete house, complete with indoor plumbing, for one of SoloCoco’s single-mom employees.

The business is growing. SoloCoco now sells its coconut oil and body-care products in more than 10 countries, and they are carried by 75 Whole Foods stores in the Northeast U.S. This growth comes with challenges, however. “Our biggest problems right now are cash flow and capital requirements,” Dalet says. “It’s harder to find startup funds in the DR, and we can’t borrow money because interest rates are high and lending for small businesses is rare. We’re all self-funded at this time.” Others in Dalet’s family contribute to the business. His wife is a certified natural skin-care formulator, and she develops the company’s organic, personal-care product line. When Dalet’s father retired from Fiat two years ago, he began working for the company in an administrative role.

Dalet says he is motivated daily by what SoloCoco means for his employees. “The most important reward has been seeing the transformation of these families and these kids,” he says.

He and his cousin hope their success motivates more entrepreneurs to come home. “If we do a good enough job with this, it’ll inspire more people to come back and build on our trails,” Dalet says. “This country doesn’t need one SoloCoco. It needs 1,000 of them.”

An Agent of Change

Alex Souza ’09 was born in Mexico City. Although his family moved to San Diego when he was 2, they returned to Mexico City in time for him to start high school. Part of the motivation around the moves was an opportunity to experience other cultures. “Our parents really wanted us to go out there and see the world,” Souza says. “If there was money to spend, we spent it on travel.”

Photo: Alicia Vera

Alex Souza ’09 founded Pixza in Mexico City to help homeless youths change their lives.

His mother, Alejandra, also instilled in Souza and his sisters the importance of helping those in need, bringing them to volunteer with Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity in Mexico City. A life coach, Alejandra taught her children that the best way to help people is by offering them tools to reshape their lives. “That’s always been a big thing in my family, to recognize that you are an agent of change,” he says. “If you want to change the world, you cannot sit around and wait for things to happen.”

When the time came for college, Souza chose Babson for its focus on entrepreneurship and the chance to live in a new place. His college years included a semester at sea and opportunities to study abroad at the London School of Economics, as well as in Uganda and Hong Kong. After college, he returned to Africa with fellow Babson alumni to start an English-language school and management-training program in Rwanda. The program included an initiative that helped underprivileged students; for every 12 students who paid full tuition to the program, one student attended tuition-free.

After successfully launching the business in Rwanda, Souza wanted to build his knowledge of social and economic development. So he sold his stake and enrolled at Columbia University for a master’s in public administration and development practice. While in school, he spent a semester in Bhutan and introduced a program that measures national well-being. After graduation, he moved to Rio de Janeiro to work with the Inter-American Development Bank, which aims to reduce poverty and inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean through financial and technical support; Souza helped establish sports programs for youths living in Rio slums.

When his contract with the IDB ended, Souza turned his attention to home. “I had already helped solve issues outside my own country and learned so much,” Souza says. “But after working in Rwanda and Uganda, Brazil and Bhutan, I decided to go back to Mexico to see what I could do here.”

Photo: Alicia Vera

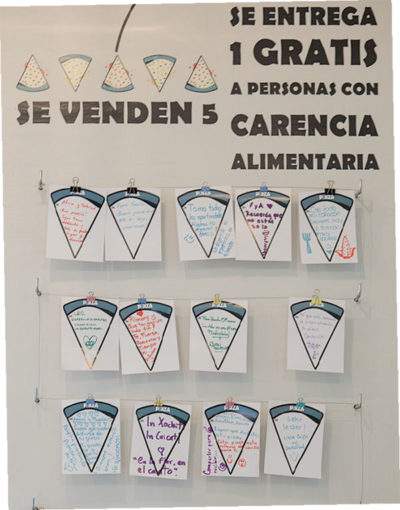

Sign inside Pixza

Souza felt drawn to the plight of Mexico City’s homeless teens and young adults, many of whom are born into homelessness. Hoping to intervene before these youths became adults, Souza began to think about ways to use his Babson-earned entrepreneurial skills. While at grad school in New York City, he had craved a Mexican food known as huarache, which is made with blue corn, and he theorized that the ingredient might make a tasty pizza crust. The idea resurfaced when he decided that a restaurant would make an ideal work experience for homeless youths. Souza spent four intense months developing a blue corn pizza crust that could be topped with traditional Mexican ingredients, including grasshoppers and zucchini blossoms. He called his restaurant Pixza (based on a common Mexican pronunciation of “pizza”), and envisioned “a social empowerment platform disguised as a pizzeria.”

For every five slices sold at the restaurant, the Pixza team donates a sixth slice to youths at a nearby homeless shelter. They deliver all the slices on Sundays. But Souza aims to do more than feed the teens. “It starts with a slice, because that’s a good reason to come together and talk,” he says. “But we want to move on to something bigger.”

Based on his previous experiences with social empowerment programs, Souza developed a detailed, multistage intervention that he calls “The Route of Change.” When youths at the shelter receive their first piece of pizza, they also receive a bracelet, which is punched each time they accept a slice. After the fifth slice, they must complete a small volunteer project of their choice, such as delivering a slice of pizza to a friend. “Instead of just being willing to receive, they have to be willing to give as well,” Souza says.

Kids who don’t complete this step are out of the program. Those who finish receive five more slices and a chance to complete a larger volunteer project. If they hit that milestone, they advance to receiving a shower, haircut, doctor’s appointment, T-shirt, and daylong life-skills course. When they complete those steps, they receive a formal job offer at Pixza, a regular salary, and a job title: Agent of Change. They get restaurant skills training and their own life coach. “The coach helps them develop a personal and professional plan,” Souza says. “Since they’ve been living on the streets, many don’t have the ability to dream.”

Professional life coaches, including Souza’s mother, usually donate time to work with the teens. In the final stages of the program, Souza and his team help participants find housing. Since Pixza launched in 2015, it has graduated and employed 23 kids, including four who have moved into housing. The entire program is funded by restaurant revenues.

Souza has opened a second location but has learned that restaurant management isn’t his strong suit, so he currently is seeking a business partner with this expertise. “I want a partner who actually loves to run restaurants, so we can open up many more locations, and I can focus on the part I’m better at, which is the social empowerment aspect,” Souza says. One day, he hopes to open an institute where he can train homeless youths for a range of roles in the food and beverage industry.

Pixza’s success has taught him the power of business to address social problems. “You can make that an objective from day one,” he says. “It’s amazing how you can use a for-profit business to make a difference.”

Photo: Greta Rybus

Jessica Wright ’11 lived in Ireland for two years, but she knew she would return to North Conway, New Hampshire, some day. Now she’s a local food systems advocate and part of a group that encourages young adults to settle in the area.

Building Communities

Jessica Wright ’11 adored her childhood in North Conway, which is in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. She was 10 when her family moved to this village, popular with tourists, skiers, and hikers. Her mother and stepfather opened the Metropolitan Coffee House in a historic building that once held North Conway’s bank. Wright and her sister spent much of their teen years working at the family business. “It evolved into this really cool community space where people would come and go for open mic night,” Wright says. “Our friends would come for teen night. Given the small town, and the central location, we knew everyone in town.”

While at Babson, however, Wright became interested in travel. She spent a semester in Ireland at University College Cork and fell in love with the place. After graduation, Wright interned with the Family Equality Council in Boston and considered law school, but she decided instead to return to County Cork in Ireland. She spent two years working as a nanny, traveling, playing rugby, and volunteering on organic farms. Those volunteer stints fueled Wright’s passion for farming and locally grown food.

As Wright prepared to leave Ireland, she applied to law school, but life as a lawyer still didn’t feel quite right. Then she found a master’s program at Vermont Law School focused on environmental law and policy. It would prepare her for a career in advocacy, and, apart from occasional on-campus courses in Vermont, she could do most of the work online, clearing the way for her to return to North Conway. “Coming back from Ireland, I just knew that I wanted to be here,” she says. “I love being in the mountains and an hour from the ocean. I love the snow and skiing. There’s nothing like hiking in the White Mountain National Forest in the fall, when the trees look like they’re on fire because the colors are so phenomenal. And I think my favorite part is that the Saco River runs right through the heart of where we live.” Wright takes frequent hikes along the water and ends hot summer runs with a dip in the river.

As she wrapped up her master’s degree, Wright began volunteering for the Upper Saco Valley Land Trust, a North Conway-based organization that aims to protect land from development. The work seemed like a good way to use her environmental law expertise to give back to the village; Wright served on the development committee and then took a part-time administrative position. When the land trust received several grants to support regional food-system projects, the leadership team used the funds to offer Wright a full-time position as a local food systems advocate, which she enthusiastically accepted.

“I work with family-scale farms to make sure that farming is a viable enterprise here,” Wright says. She leads collective efforts to help farmers market their products, creating and maintaining directories that allow customers to find local food, and working to promote area farmers markets. Wright feels lucky to spend her days visiting local farms, checking out greenhouses, fields, and farm animals. “That’s what I’m working for, to make sure that these people can keep doing what they’re so passionate about,” she says.

Photo: Greta Rybus

Jessica Wright works for the Upper Saco Valley Land Trust.

But Wright’s choice to live in North Conway also involves some sacrifice. Because it’s a tourist area, housing can be expensive. At the same time, salaries typically lag behind those in cities, so Wright holds a second job as a bartender to help pay her student loans and mortgage. Also, few other permanent residents are in their 20s or early 30s. “People who might want to put down roots are delaying that until they’re 35 or 40,” Wright says. “They work on their careers in Boston or Portland or Portsmouth and wait until they have a better handle on their finances to come back and raise their families.”

Hoping to find solutions, Wright is chair of a group known as STAY MWV, for Supporting the Active Young Professionals of the Mount Washington Valley. In 2016, the group established a student debt scholarship that helps pay recipients’ loans for up to a year. “We’ve had so many discussions about the apparent lack of young people and examined the barriers to living up here,” she says. “If we could alleviate student debt for someone for one year, think how much more engaged they could be in their community. They could leave that second job and coach soccer or save for a house.”

Wright plans to continue her efforts to convince young adults to commit to North Conway. “The best thing about the work I do is knowing I’m benefiting the community that helped raise me, that’s helping raise a whole new generation of children, and where I’ll hopefully raise my own children one day,” she says. “That’s so rewarding.”

]]>

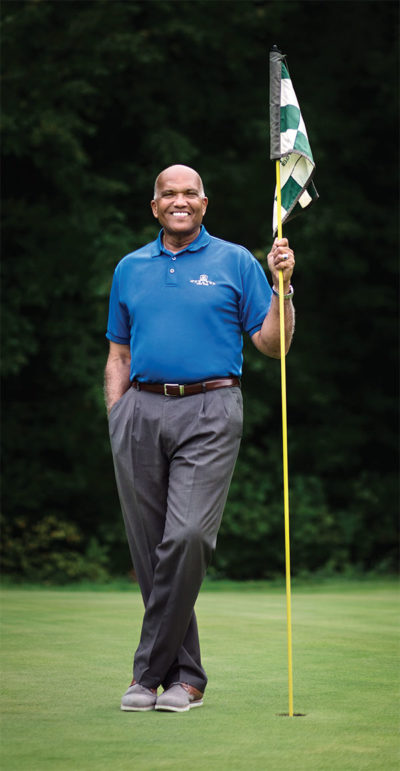

Photo: Ryan Donnell

Henry Turner, MBA’89

How’s your golf game? Do you play a lot?

I don’t. I’m just starting to pick up the sport now. I actually bought the course for land development. But after buying it and seeing its value to the community, I decided to keep it. My wife is from Mississippi. In the early 1990s, we were looking for property to build a house there. A Realtor was showing us around. It was a very nice neighborhood with a golf course. I said, “I want to go over there and play.” He said, “You won’t go over there and play at that golf course.” I forgot I was in Mississippi. Now I don’t need that golf course. I have my own. We are open to everyone. Our fees are the lowest in the area.

What are your hopes for Marlton?

I want the younger population to realize that business owners use the golf course as a way to conduct high-level business. There is not one deal struck on the football field or basketball court. Every day there is a business deal struck on the golf course.

What has the military meant to your family?

Our father spent over 30 years in the military. He started in the segregated army, got his optometry degree, and went back into the Army as an optometrist. The military gave him an opportunity, an opportunity the rest of society didn’t give minorities. My two brothers and I went to West Point, my sister went to the Naval Academy. All of us spent 20-plus years in the military. The military is a wonderful thing. It paid for our education. My wife, Winifred, served 22 years in the Army and retired as a lieutenant colonel. Our oldest son is a major in the Army. Service is important to our family. So much has been given to us. There comes a time when you have to give back.

What’s an essential lesson the Army taught you?

If you take care of your soldiers, your soldiers will take care of you. That’s the biggest thing I learned in the military. And I took that into the civilian world. If you take care of your employees, your employees will take care of you.—John Crawford

Photo: Tom Kates

David Abdow, dean of Babson Executive and Enterprise Education

David Abdow grew up in a family business. His father and uncle owned a Big Boy franchise with stores in western Massachusetts, where they lived, as well as in central Massachusetts and greater Hartford, Connecticut. “I certainly did my time washing dishes and working in the warehouse through my high school and college years,” says Abdow.

He studied political science at Brown University. During his undergrad years, Abdow also took a year off and went to Colorado, where he focused on work with a social impact. “The goal was to develop people’s sense of efficacy and their ability to impact the kind of change that they wanted in their communities,” he says. “I was issue agnostic. I saw my role as an enabler. And that sparked my interest in adult learning.”

Abdow taught high school social studies. After earning a master’s in education, he tried his hand in the classroom for a year but then joined his family’s business. “There was an opportunity to get into the business in a way that was appealing to me, which was in the training and development space. It was one of those now-or-never times to see if it was going to be right for me,” he says. Abdow stayed for close to five years before deciding to pursue work with more of a social impact.

He has more than 21 years of experience in higher education. Before coming to Babson, Abdow worked at the Center for Corporate Citizenship at Boston College and in roles related to executive education and corporate relations at Northeastern University’s D’Amore-McKim School of Business. So Abdow knows how to facilitate and manage partnerships between colleges and corporations, but he likes how BEEE goes beyond corporate learning. “We also have a startup and scale-up space that has a significant social and economic impact,” he says, citing such programs as Launch and Grow for Kenyan women entrepreneurs and Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses. “In addition, we work in the academic sector, where our mission is to export our model for entrepreneurship education to other parts of the world.”

Abdow loves sports. As a youth, he was a wrestler and played football and lacrosse. He met his wife skiing, and now his family (they have two children) enjoys the sport. “We also like tennis and golf,” he adds.

He was an Outward Bound instructor in Maine. Abdow took youths and corporate groups on backpacking and canoeing trips. “When you are coming off a day that was incredibly physically challenging, and you were learning new skills like using a map and compass, and then you have to set up camp and cook dinner and do things in the dark, and you’re interdependent on each other to get through these activities—that’s when people tend to show their true colors,” he says. “You learn from that. You learn about yourself, and about others. And perhaps that has an impact on how you think and do things after the experience.”

Abdow is inspired by his father and Nelson Mandela. “I was very impacted when I read Mandela’s autobiography. Some people have a calling in life,” he says. “My father is a role model in the way that he manages his relationships across all of his worlds, which include family, business, and community. He has worn many, many hats over the years, and has worn them well.”—Donna Coco

]]>When MOOCs burst onto the scene almost 10 years ago, they were greeted as higher education’s savior—or its downfall. The free online classes held out the promise of bringing college within reach of anyone with internet access. But some observers feared that access could undermine the traditional college model. Nonetheless, many colleges and universities got on board. Both the dire predictions and the overblown promises have yet to be realized, but one thing remains clear, says Parise: “MOOCs are not going away.”

Illustration: Dave Cutler/theispot.com

EdX began as a collaboration between MIT and Harvard and is now a leading provider of online courses, with more than 70 schools on board. Babson joined edX because it offered the support and reach the College sought in the MOOC marketplace. The first six courses that Babson is offering—a basic business suite covering such topics as financial analysis, marketing fundamentals, and the entrepreneurial mindset—were launched in January.

Translating Babson’s content into online courses proved to be no easy matter—even for those who have created digital content for the College’s blended learning programs. “I thought it would be a simple migration,” says Mark Potter, professor of finance. “And that was wrong.” One big difference, he says, is the sheer size of the classes: 50 or so in a blended learning MBA class, compared with perhaps 5,000 in a BabsonX class. BabsonX classes are designed to run both “live,” in real time, and “self-paced.” But even in live classes, it simply isn’t possible to interact with every student. So professors connect with students beyond the “classroom” through discussion boards, which Potter says he enjoyed, spending a couple of hours a day on the boards during the four weeks of his live class.

The static nature of online material also proved a challenge. “During a typical class, I like reading students’ reactions and adapting on the fly,” Potter says, “and all of a sudden, I’m talking to a camera.” But Potter says the academic technologies team, headed by Eric Palson, has done an exemplary job of designing and creating content in partnership with faculty members. It’s not just a matter of pointing a camera at a professor and letting him or her talk, says Palson. “That can get very boring, very fast,” he says. His team works with faculty to create graphics, animated segments, and more to ensure the courses are visually compelling as well as intellectually engaging.

Creating the online courses represents an investment of time, money, and resources. But supporters of the effort cite a slew of potential benefits for the College, from raising awareness about Babson to increasing enrollment to connecting with alumni to providing prerequisites for admitted grad students to sharing the College’s mission. Although the program is still in its early stages, by those measures it’s already a success. Says Potter: “We can reach so many people who wouldn’t ordinarily get touched by Babson’s curriculum and staff. The investment was a pretty small price to pay.”—Jane Dornbusch

]]>

Illustration: Christian Roux

As the saying goes, art is where you find it. Thanks to John-Marshall Stubbs, MBA’14, art now can be found on one of the unlikeliest of canvases: swimwear. Stubbs selects original, colorful paintings and then adapts them for imprinting on men’s and women’s swimsuits, which he sells through his company, Curated Clothing.

Growing up in Dallas, Stubbs was immersed in art—and commerce—from a young age. His mother owned a gallery, and he spent his early years visiting galleries and art fairs. After college, where he majored in art history and minored in business, he ran a second outlet of his mother’s gallery.

But the entrepreneurship bug also bit him early, so he soon came to Babson for his MBA. Shortly after graduating, Stubbs came across a process called sublimation printing, which makes it possible to reproduce high-resolution images on polyester fabric. Inspired, he pondered the potential of various printed products before having a eureka moment: “At three in the morning, I shot out of bed and wrote down ‘swimsuits,’ so I wouldn’t forget it.” That was in July 2014; he set to work researching manufacturers and had his first sample suit ready that December.

Today, Curated Clothing sells numerous styles online and in several retail stores. The business has changed the way Stubbs looks at paintings. “Now, when I see a piece of art,” he says, “I think in terms of how I can cut it up and put it on a swimsuit.” Stubbs also has become skilled at manipulating images in Photoshop to make them swimsuit-ready.

His cred as a former gallerist makes artists comfortable working with him, says Stubbs. Each suit is labeled with the artist’s name and signed, and Stubbs, who works with about 16 artists, takes his mission seriously. “I’m not just buying an image,” he says. “It’s an art gallery you wear.”

Now living in Los Angeles, Stubbs wears his own creations frequently. “I go to the beach a couple of times a week,” he says, “and every time, someone says, ‘That’s a cool swimsuit.’”

]]>

Photo: Webb Chappell

Babson President Kerry Healey

In 1919, when Babson was founded, classes were held at Roger Babson’s home on Abbott Road in Wellesley. Two years later, Roger purchased 125 acres of farmland to serve as the future campus for the young school, and in the nearly 100 years since, that campus has continued to grow and evolve. This fall, as I inducted members of the Class of 1967 into the Half-Century Club (one of my favorite events), many of those alumni remarked that they barely recognized the Babson campus—it has been so transformed over the past 50 years.

Today, we are embarking on our next wave of transformations and planning a campus for our second century.

In September, we broke ground on a new recreation and athletics center. This project is among the most ambitious ever undertaken by Babson. When completed, it will provide a venue for events and recreation, a place for members of our entire campus community to invest in their health and well-being, and a beautiful new home for Babson Athletics and our incredible scholar athletes (see “New Construction Project to Transform Campus Life”).

The Weissman Foundry, which also broke ground in September, will be a flexible maker space focused on hands-on experimentation and prototyping. Designed with input from Olin College, it is envisioned as a cross-campus workshop where entrepreneurs of all kinds can collaborate, turn ideas into action, and create tomorrow’s products and enterprises (see “A Hands-On Space for Students to Innovate”).

The Weissman Foundry is particularly special because it is named in honor of esteemed Babson alumnus and trustee Robert Weissman ’64, H’94, P’87, ’90, and his wife, Jan, P’87, ’90. This fall, we were delighted to announce that the Weissmans made a $36.6 million gift to Babson, bringing their lifetime support to a record $100 million. We are deeply grateful for the Weissmans’ commitment to our community and belief in Babson’s unique ability to advance entrepreneurship everywhere.

A portion of their gift will enable us to construct a new learning common and gateway to Horn Library, featuring a four-season garden, a cafe, collaborative work areas, informal gathering spaces, and a new home for the Stephen D. Cutler Center for Investments and Finance. It also will serve as a central location for Babson’s academic and extracurricular resource centers and provide additional classroom and office space.

As we approach our Centennial, we are excited to further create spaces that will enable Babson to remain the global leader in entrepreneurship education, attracting the best and brightest students from around the world, providing an unmatched student experience, and educating entrepreneurial leaders who will change the world for the better.

Kerry Healey

]]>So Kokina asked her parents for a tutor. Eventually, she studied English in school as well. “But for a couple of summers, all I remember is me and my English tapes and listening to the BBC radio a lot,” she says.

Coming from a family of educators, Kokina grew up in an atmosphere where curiosity and learning were encouraged. Her father was a teacher and then principal at a vocational school. “My favorite memory from childhood is my father taking me to his class, and it was all boys,” she says. “I really felt special when I was the little kid sitting at his desk, and he was showing me around.”

Her sister, who is 14 years older, was actually her teacher one year in elementary school. Her mother, an economist, instilled in Kokina a passion for math. A desire to learn about new cultures brought Kokina to El Paso, Texas, on a Rotary exchange program for her senior year. Even the parents of her U.S. “family” were educators. “Education has shaped my life in a big way,” she says.

Photo: Tom Kates

Julia Kokina, assistant professor of accounting, at Fava Bean Mediterranean, the restaurant she co-founded with her husband.

Entrepreneurship also intrigued Kokina from an early age. In Latvia, she saw her country gain independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Afterward, many people started businesses, and Kokina saw how those ventures positively affected their lives. Later, as a student in El Paso, she noted how entrepreneurship and small businesses helped shape the communities on the border of the U.S. and Mexico.

“I saw how entrepreneurship can change lives,” she says, which prompted her interest in studying business and accounting. But instead of heading back to Latvia for college, Kokina, who liked her independence and wanted to continue exploring new cultures, decided to study at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP).

Her sophomore year turned out to be pivotal. Juarez, Mexico, which borders El Paso, was dubbed the violence capital of the world that year, Kokina says. She and fellow students staged events for V-Day, the global movement aimed at ending violence against women. “We were staging protests on the border and raising money for shelters,” she says. “I continued that kind of work throughout college.” Kokina also founded a Rotaract club on campus and met her future husband. “It was probably the most monumental year of my life,” she says.

Working with shelters, Kokina found herself thinking entrepreneurially about how to raise money for them. She set up huge garage sales, receiving items from the entire Rotary community in El Paso, and donated the proceeds to shelters. She also started a greeting card project, asking children at a shelter to draw cards, finding a volunteer designer to help create the cards, and then printing and selling them. Again, all proceeds went to the shelter.

Upon finishing her undergraduate degree, Kokina decided to continue her education at UTEP, earning a master’s and becoming a CPA. While studying, she took a job as a tax accountant and then senior auditor, for which she helped train employees. Something clicked. “That’s when I realized I enjoy teaching,” she says, and so she decided to stay even longer at the university and earn a PhD in international business.

In 2014, nine years after arriving in the U.S., Kokina finished her studies and had seven job offers. She chose Babson because of its focus on entrepreneurship. Now as a member of the accounting division, conducting research and teaching courses in an entrepreneurial environment, Kokina has a job that encompasses all of her passions.

Kokina researches innovations and emerging technology in accounting, so she explores such topics as analytics, artificial intelligence, and blockchain technology. “You have to follow up on what the industry is doing,” she says. “You’re not just preparing students to pass an exam. You’re preparing them for when they walk into a company and are expected to know these technologies and recognize opportunities for them.”

This fall, her classes include “Accounting Analytics,” which she helped develop for the MS in Accounting. The course examines such topics as how a company would use analytics to evaluate its performance. “That might involve figuring out which metrics determine your performance, and how you would develop systems of measuring financial and non-financial performance,” she says.

The entrepreneurial spirit still lives within Kokina as well. In June 2016, she and her husband opened Fava Bean Mediterranean, a fast-food restaurant in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that focuses on cuisine from the Middle East, including Yemen, the homeland of her husband’s family. “My husband’s family is in the restaurant business,” Kokina says, “and he has always had a dream of being his own boss. My involvement has been research, development, financial analysis, strategic thinking, and constant support.”

Kokina shares what she learns from the business with her classes, and sometimes she seeks advice from her students. “I might ask them, what do you think about Snapchat? Will this work with your population?” she says.

Being a professor is exciting, says Kokina. “The opportunity to learn,” she says, “and to keep up with what’s going on—it’s fulfilling and motivating.”

]]>

Photo: Justin Knight

Rachel Pardue ’19 (left) and Michelle Cedillo ’19 outside of Van Winkle Hall, which houses the full-stack community

Babson’s full-stack community consists of eTower, a hub of entrepreneurship on campus founded in 2001; Community of Developers & Entrepreneurs, or CODE, a group of students interested in coding and technology; and theStudio, whose residents pursue a range of creative and artistic endeavors. The hope is that the groups’ close proximity—they occupy three successive floors of Van Winkle—will create synergies that inspire and enable entrepreneurial projects.

But the three communities didn’t start out as a joint venture. While eTower has long been a popular residential choice for students hoping to create businesses at Babson, CODE and theStudio are of considerably newer vintage. Both were launched in the fall of 2016, and both grew out of perceived needs on campus. Waseem Shabout ’19 and like-minded students founded CODE as a club, with the eventual goal of creating a tech-themed living community. He and others in CODE were fans of the eTower community, and when the time came to plan a residential space, says Shabout, “We requested that we be directly beneath eTower.”

At about the same time CODE was being formed, Michelle Cedillo ’19, who is serving as co-president of theStudio, sent her friend Julia Dean ’19 a message: “‘Hey, we should make an arts organization.’ We wanted a space with a purpose, to kind of get messy and make things.” Like Shabout, Dean and Cedillo founded a club, Create, in part to pursue a special-interest living community. Unlike CODE, theStudio didn’t request housing in a particular location. But its serendipitous placement near the other two made collaboration seem only natural.

Still, it took an apparently spontaneous remark to turn it into a cohesive community. Shabout recounts that he and some of the leaders of eTower and theStudio met one day early last spring to discuss plans for the semester over a tub of day-old brownies. “We were trying to put together a collaborative fundraising event between the three organizations. Then someone said, ‘It will be a full-stack event!’ and we all laughed.

“And then,” he continues, “we all kind of realized that’s exactly what Van Winkle was: a full-stack community. It was kind of a play on words, but it’s still relatively true.”

“You had technical, creative, and entrepreneurial people who just wanted to work together. It came about very organically,” says Rachel Pardue ’19, who is serving as eTower president this year.

The community, it appears, is conducive to entrepreneurship. Shabout and other members of CODE and eTower co-founded Jinn Tech, a startup consultancy, while living in Van Winkle, drawing on the resources that were literally all around them. “If I had a question about anything, whether it was to do with my business or my homework, I’d go upstairs, I’d go downstairs, and there was always someone willing to engage,” says Shabout.

Residents are hoping for more collaborations going forward. Says Pardue, “I think that this is going to be a really defining year for us coming together as a full-stack community.”—Jane Dornbusch

]]>