The pro basketball player had skills. A sharpshooter, he stood 7 feet tall and proved amazingly accurate from three-point range.

There was just one problem: During games, he didn’t want to shoot. “It was frustrating,” says his former coach, Norm de Silva ’09. “He would rather just pass. I had to literally beg this kid to shoot.”

De Silva wasn’t accustomed to such an attitude. Watch a U.S. college or NBA game—players want the ball in their hands, and they’re not afraid to launch it toward the basket. But this wasn’t the U.S. De Silva was head coach of the Foshan Long Lions, a team that plays in China’s professional basketball league. In China, de Silva discovered that while the rules of basketball were the same, the game can be quite different.

The Lions’ talented 7-footer came from a poor farming town, and he didn’t want to ruin the financial opportunity that being a member of the team had provided. “If he became the focal point, and the team didn’t do well, he worried that he would face blame,” de Silva says. “He would rather not take the risk.” So even though he was a great player, the young talent didn’t like all the playing time de Silva hoisted on him. Through a translator, he asked his coach during games, “Do you want to play someone else?”

Another World

To hop on a plane, fly thousands of miles, and land in a country much different than his own was a big step for de Silva. “I had never left the country until I stepped off the plane in China,” says de Silva, who grew up in Massachusetts. “I didn’t even have a passport before getting the job.”

But de Silva was dedicated to making a career in basketball. He had experience, having previously worked as an assistant coach in the college ranks and with two teams in the NBA’s minor league system. So when the opportunity came to coach in China, which is hungry to learn from the basketball-savvy Americans, he decided to go for it. The position offered good money and a chance to further his career, but de Silva wasn’t prepared for feeling so lost and overwhelmed by the foreign land. “It was crazy,” he says. “My head was on a swivel at all times. You think, holy crap, what have I gotten myself into?”

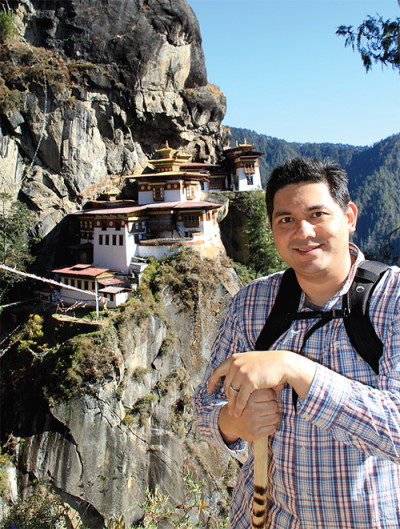

Lawrence Ganti ’97 has lived in Switzerland, Japan, and India, where his work for Merck brought him to Bhutan, shown above. He currently resides in Brazil and is Merck’s Latin America president.

Lawrence Ganti ’97 knows this feeling well, though while growing up in New Jersey, he admits that he didn’t think much about the rest of the world. Ganti’s views started to change at Babson, where he met many international students, and after obtaining his MBA overseas, he has lived and worked in Switzerland, Japan, and India. With his wife and two well-traveled dogs, he currently resides in Brazil, where he is the Latin America president for Merck.

When you first settle in a foreign country, where everything is new and unfamiliar, your brain is overloaded, Ganti says. “The first few weeks are like drinking from a fire hose. Everything just hits you. There’s no break,” he says. “Turn on the TV, it’s all in Japanese. Go to Starbucks, it’s all in Japanese.” At times, in the middle of this cultural onslaught, Ganti found himself just longing for a pizza.

Before Cyrus Sabouri ’08 left New Jersey for the island nation of Bahrain, where he works for American Express Middle East, he felt the enormity of what he was about to do. “It was about going into the unknown,” says Sabouri, head of the Revolve (interest-bearing) products portfolio and membership rewards program. “You don’t realize what you’re doing until you hug your mom and realize you won’t be back for a long, long time. That was a difficult goodbye.”

Then he landed in Bahrain, where the October temperatures soar into the high 90s, the taxi drivers continually tried to overcharge him, and his temporary housing was next to a fish market. “It was the most foul smell to come home to every day,” he says. “It didn’t feel like home at all.”

Sabouri’s parents were born in Iran and came to the U.S. in the 1970s, and, as he grew up, they encouraged him to see the world. “The globe is your playing field,” they told him, and he took their words to heart. But those first few weeks in Bahrain were a test, a crash course in a new way of life. “It was a scary time of transition,” he says. “You’re confronted with different kinds of people, a different language, and a feeling of self-doubt.”

Over time, those doubts fell away and Sabouri made friends. But as with anyone living abroad, the adjustments to his new home continue. The unavoidable truth is that he’s different. Conspicuously so. When Sabouri goes to a coffeehouse with a Bahraini friend, the American is conscious of how clunky his Arabic is. Sabouri also doesn’t wear a thobe, a traditional ankle-length garment worn by many Bahraini men. “You can pick me out from a mile away,” he says. During Ramadan, a holy month when people spend much time with their families, Sabouri becomes acutely aware of just how far away he is from his own loved ones. “Everyone is together with their families,” he says. “What can you do when you’re a single bachelor?”

Differences in Business

In the office, cultural differences can play out in multiple ways. When Ganti’s work with Merck first took him to Japan, he was struck by how comfortable his Japanese co-workers were with silence. During meetings in the U.S., people are typically uneasy with quiet and fill a lull with talk. Not so in Japan. Even lunchtime is carried out in a hush. “You don’t break the silence unless you have something relevant to say,” says Ganti, who learned to measure his words before speaking.

Ganti also came to recognize that the Japanese value the team over individuals. When dealing with the review of a poor performer, for instance, he started using the word “we” a lot. He would tell an employee, “We need to make improvements,” or “We can solve it together,” diverting the emphasis away from the individual. “It isn’t about throwing a guy out on the ledge and saying you need to handle this on your own,” Ganti says.

The Japanese value the building of trust and relationships, he adds. In Japan, nothing might be accomplished in an initial meeting, as everyone gets to know each other, and no real progress may be made until the parties sit down for a lunch or dinner. Ganti remembers greeting foreigners who flew to Japan with the intention of holding their meeting and flying out that same day. “It’s just a half-hour discussion,” they told him. He replied, “That half-hour discussion won’t go anywhere.”

Sabouri has experienced a similar emphasis on relationship building in the Middle East. “Meetings can require personal introductions, which often consume more of the meeting than the agenda itself,” he says. Sabouri was frustrated by this custom when he first moved to Bahrain. “You eventually learn that there can be a fine line between business and personal life,” he says. “Warm and hospitable introductions can be the difference between deal and no deal.”

Dedicated to making a career in basketball, Norm de Silva ’09 (right) has served as head coach in China of the Foshan Long Lions and in Japan, shown above, of the Kumamoto Volters.

De Silva faced some tricky cultural differences when coaching in China, particularly in regard to the team’s intrusive management. De Silva began as an assistant coach with the Foshan Long Lions, but when the team got off to a bad start and the organization’s higher-ups brought in a consultant to help stem the tide, the Lions’ American head coach resigned over the intrusion. De Silva then was named head coach, albeit an interim one with a narrow margin for error.

De Silva had never been head coach before, and his first game leading the Lions was broadcasted all over China. “National TV over there is like a fifth of the world’s population,” he says. During that first game, the team’s owner, general manager, and consultant grabbed de Silva in the hallway and told him what to do and who to play. De Silva respectfully nodded his head and then ignored their directives. The team won. “If we had lost the game, I wouldn’t have been the coach the next day,” he says.

For a while, de Silva wondered from day to day whether he would be fired. “It was rocky waters at first when I took over,” he says. Under his direction, however, the team kept winning. The Lions went 10 and 5, which set off a sensation. His face was plastered on billboards. The national paper ran a front-page picture of the 5-foot-8-inch de Silva, the headline reading, “Small Man, Big Wisdom.” When he left the gym after a practice or game, a hundred people would be waiting to take his picture or get his autograph. “I’m sure my head was inflated,” de Silva admits. A filmmaker even began following him around, and the resulting documentary, Jiaolian [Coach], played in film festivals.

Despite the success, the team’s executives were frustrated with de Silva, who continued to ignore their edicts. “It’s hard to navigate the management in China. The people in power are never challenged,” he says. “Every time the GM saw me not listen to the consultant or owner, it really questioned their status. It was risky for me to do. They knew I couldn’t be controlled, and that was scary for them.” But with de Silva so popular in the media, the team never disciplined him. They waited until the season ended to inform him he wouldn’t be brought back.

While he had trouble with the team’s management, de Silva got along well with his players, who respected his authority. “If you are the coach, whatever you say goes,” he says, an attitude that contrasts with what is often found in the NBA. “A professional player in America thinks they know more than you do,” he says.

How to Navigate

Figuring out how to handle these cultural differences takes time, note all three alumni. Being flexible is key, says Ganti, as is pushing aside any preconceived notion. “I never take the approach that it’s not the way we do it in America,” he says. To better understand a country’s culture, Ganti likes to explore his new settings and is not afraid to get lost. He avoids hanging out with fellow ex-pats, instead seeking the company of locals. “As many Americans, I am linguistically inept,” he says, but adds, “I’m generally a fast learner when it comes to culture. I find cultural understanding is as important as understanding the language.”

Working for American Express Middle East, Cyrus Sabouri ’08 has been based in Bahrain for seven years, but his job takes him all over the Middle East and North Africa, including to Egypt.

Remember how Ganti grew accustomed to respecting silence in Japan? He next lived in India, where conversations are boisterous and full of interruptions. “Silence is never expected,” he says. “You can’t get any more different than Japan and India.”

Ganti’s current job with Merck takes him throughout Latin America. Each country presents its own cultural puzzle to figure out. Sometimes, he chooses to ignore culture. In many parts of Latin America, for instance, giving direct feedback in conversation isn’t typical. So to make a point, he may do just that in meetings, and attendees are taken back. “I’m usually sent places where change is needed,” he says. “Sometimes to make change, you have to rock the boat.”

Like Ganti, de Silva has had to make adjustments when moving from one country to another. After working with the amenable basketball players in China, he next spent a season coaching the Kumamoto Volters, a professional team in Japan, where de Silva discovered how important one’s age is. “In Japan, you don’t challenge someone older than you,” he says. “I’m a young coach. At least eight of the guys on the team were older than me.” The older players listened to de Silva, but they also reminded him in subtle ways that they were superiors from an age standpoint. “They would stop practice and ask, respectfully, why I wanted to do something a certain way. They would never do that in China,” says de Silva, who, after being let go by the cash-strapped Volters now works as a scout with the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers.

For Sabouri, the key to navigating cultural differences is curiosity. His American Express office oversees 18 markets across North Africa and the Middle East, and so to understand those markets better, he likes to travel to the associated countries, talk with people, and ask questions. How do people dress? What do people like to do on the weekends? What’s the political situation? “If you have a curiosity, it changes your perspective,” Sabouri says. “You are no longer bound by your home country.”

Sabouri has worked in Bahrain for seven years now. He plans to return permanently to the U.S. one day, and when he does, Sabouri knows he’ll have a greater understanding for what the world offers. His time in Bahrain has changed him. “I am grateful to have matured as a professional, adult, and citizen of the world,” he says. “It’s been an incredible ride.”