When superstar quarterbacks Tom Brady and Peyton Manning finally decide to retire from football, their departures will cause a lot of hubbub. Reporters will pack a goodbye press conference, ESPN will run career retrospectives, and fans will mourn the loss of two giants of the game.

Most careers in the National Football League, however, don’t end with such a fuss. One day the players simply may be cut from a team, and all they can do is hope that another team picks them up. “They keep working out,” says accounting professor Fred Nanni, “and wait for the phone to ring.” Sometimes it does, but eventually, it will remain silent. Just like that, a player’s NFL career, something he has dreamed about since he was a boy, will be over.

Nanni is faculty director of “Basic Training: It’s My Business,” a new entrepreneurship program created by Babson Executive Education that’s aiming to help players with their postfootball lives. The average length of an NFL career is only 3 1/2 years, which means many players are in their mid-20s when they leave football. “They’re trying to figure out what to do for the next 40, 50 years of their lives,” says Bahati VanPelt, executive director of The Trust, an organization run by the NFL Players Association that offers career, health, and financial services to ex-players. The Trust partnered with Babson to provide the “Basic Training” program, which launches its first class in late June.

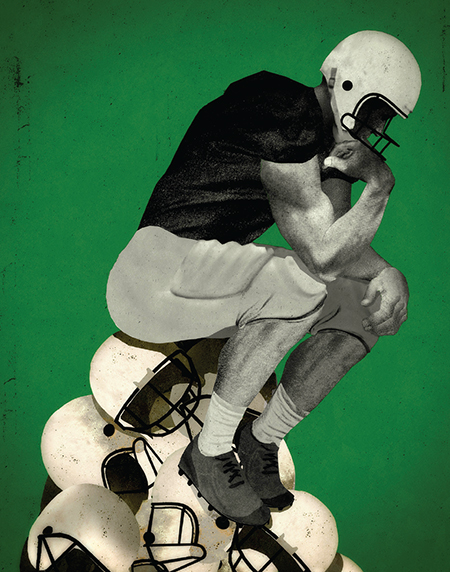

Illustration: Brian Stauffer/theispot.com

To leave the big hits and bright lights of the NFL isn’t easy. Some ex-players struggle with depression and financial issues. They may have health problems, due to the tremendous pounding their bodies took on the field, or their relationships may be strained because they’re now around the house all day. “It’s a challenging transition,” VanPelt says. “All they know is being a football player.”

Coaching and broadcasting are two obvious career paths for ex-players, but many have an interest in entrepreneurship. “They are competitive people by nature,” VanPelt says. “The challenge of running a business is attractive to a lot of former players.” On first blush, entrepreneurship may not seem like a natural fit for brawny athletes, but the job of football players is to stand back up, again and again, after being knocked down. “They have a strong belief in themselves,” Nanni says. “They know they’ve got to keep pushing. That’s a big part of being a successful entrepreneur.”

But while the players are tough and confident, they may not be aware of how complicated and time-consuming the entrepreneurial process can be. During the course of three days, “Basic Training” will lay out what starting a business involves. The program hopes to serve as a reality check. “We plan to be very frank with players,” VanPelt says. “Having a great idea and a great business are two separate things. Just because you like to eat out doesn’t mean you should open a restaurant.”

Demand has been strong for “Basic Training,” with 50 explayers expressing interest in the program’s initial 25 slots. BEE also plans to offer another course, one for ex-players who already own a business, in the future. VanPelt envisions The Trust building a long-term relationship with BEE. “I’m excited to be working with Babson,” he says. The relationship means that Nanni will need to grow accustomed to teaching students who are a lot bigger than the typical BEE participant. Nanni stands 5 feet 6 inches tall. “When I walk into the room, that will be pretty funny,” he says.—John Crawford